c. 1765-c. 1828

After more than 100 years of colonial settlement, any expectations the Puritans may have had that their religious communities would expand and dominate the continental landscape were brushed aside by generations of immigrants seeking land, personal fortune and driven by the desire for freedom and self-determination. Religious and/or Puritanical ideas and habits persisted in one form or another throughout all of the colonies (as they do to this day), but a universally God-centered society was no longer even in contemplation among the hordes of colonists, explorers and settlers streaming into the colonies and pressing out into the western wilderness.

After more than 100 years of colonial settlement, any expectations the Puritans may have had that their religious communities would expand and dominate the continental landscape were brushed aside by generations of immigrants seeking land, personal fortune and driven by the desire for freedom and self-determination. Religious and/or Puritanical ideas and habits persisted in one form or another throughout all of the colonies (as they do to this day), but a universally God-centered society was no longer even in contemplation among the hordes of colonists, explorers and settlers streaming into the colonies and pressing out into the western wilderness.

This shift away from theocentricism had its official beginnings in Europe in the early 1700s when philosophers and academic professionals introduced the notion that religion could be enhanced and improved by means of the human faculty of reason which, they pointed out, is also a gift from God. They argued that human reason, logic and the fruits of the scientific research then gaining in popularity throughout Europe were not necessarily opponents of theology but, instead, could provide a healthier and more spiritually fulfilling means of living one’s faith on an individual basis. This era is commonly referred to as the “Enlightenment” or the “Age of Reason.”

What we refer to as the Revolutionary Era in American literature, therefore, is the result of a combination of all of these factors, the latter of which was imported into the colonies via the established book trade. Colonists and settlers in America still relied primarily on journals, tracts and books from Europe for their information and instruction because they were still the subjects of Great Britain and wanted to stay up to date on all of the events and advances of their native countries and countrymen. By immersing themselves in the tracts and publications of the Enlightenment thinkers of their time, a strong awareness developed that, as British citizens, American colonists deserved the same rights and considerations accorded to the people in the home country. It quickly became apparent, however, that the English Parliament only viewed the colonists as servants to be used for the financial enrichment of England and otherwise to be accorded no rights or privileges as citizens at all.

What we refer to as the Revolutionary Era in American literature, therefore, is the result of a combination of all of these factors, the latter of which was imported into the colonies via the established book trade. Colonists and settlers in America still relied primarily on journals, tracts and books from Europe for their information and instruction because they were still the subjects of Great Britain and wanted to stay up to date on all of the events and advances of their native countries and countrymen. By immersing themselves in the tracts and publications of the Enlightenment thinkers of their time, a strong awareness developed that, as British citizens, American colonists deserved the same rights and considerations accorded to the people in the home country. It quickly became apparent, however, that the English Parliament only viewed the colonists as servants to be used for the financial enrichment of England and otherwise to be accorded no rights or privileges as citizens at all.

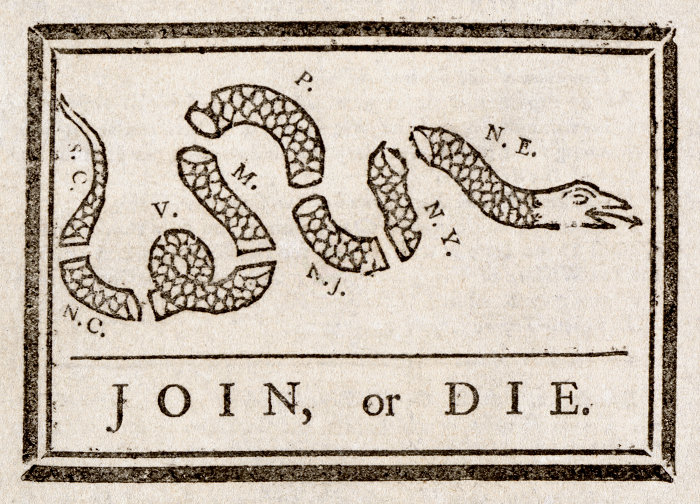

Passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 officially set the American Revolution in motion. Years of studying and absorbing the philosophies and ideas of the great Enlightenment thinkers about human freedom and every man’s right to self-determination and self-government, combined with an increase in open discontent with abusive taxes and conditions imposed by the English Parliament, led to the uniting of American colonists to oppose what was viewed as Britain’s insufferable abuse of power – and eventually to  declare complete independence from England altogether.

declare complete independence from England altogether.

From 1765 until about 1790, most of the literature produced in America focused on rational or political topics, motivating and inspiring citizens throughout the colonies to resist British rule and to develop what would become the independent nation and government of the United States. Printing presses began to increase in number throughout the colonies, newspapers and political tracts proliferated and, by 1790, a more nationalistic attitude was starting to take root in the population.

It was during these years, from 1790 to about 1828, often referred to as the “Early National Period,” that Americans began the process of refining their national identity as separate from their European origins and traditions. Publishing continued to spread and thrive and, with it, the development of new forms of poetry, fiction and nonfiction. Essays and sketches gained popularity and early efforts were made in the forms of novels and narratives. “Slave narratives,” already present in previous generations, increased in publication and popularity as well.

Revolutionary Era Literature

The following authors in our database represent the Revolutionary Era of American Literature:

| Adams, John |

Henry, Patrick |

|

| The U.S. Articles of Confederation |

Jefferson, Thomas |

|

| Ashbridge, Elizabeth |

Murray, Judith Sargent |

|

| The U.S. Bill of Rights |

Occom, Samson |

|

| Brown, Charles Brockden |

Paine, Thomas |

|

| Brown, William Hill |

Palou, Francisco |

|

| Centinel |

Rowson, Susanna Haswell |

|

| de Crevecouer, J. Hector St. John |

The U.S. Constitution |

|

| Edwards, Jonathan |

The U.S. Declaration of Independence |

|

| Equiano, Olaudah |

Tyler, Royall |

|

| Foster, Hannah Webster |

Warren, Mercy Otis |

|

| Franklin, Benjamin |

Washington, George |

|

| Freneau, Philip Morin |

Wheatley, Phillis |

|

| Hamilton, Alexander |

Woolman, John |

|

| Hammon, Jupiter |

Click on any of the above names to open the corresponding biographical essay.

Click on the red book icon ![]() to the left of any name in the list to access that author’s bibliography and our collection of direct links available for the associated titles as hosted by a wide variety of professional and academic Web sites.

to the left of any name in the list to access that author’s bibliography and our collection of direct links available for the associated titles as hosted by a wide variety of professional and academic Web sites.

Are there other authors you think should be included in this category?

Let us know and we’ll try to add them whenever possible.

Register now for a Free Membership to CurricuLit.com and you will receive notices of special features and updates as they become available.