Author Biographies 13

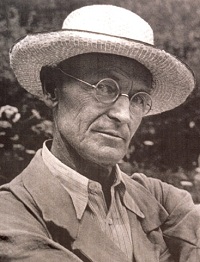

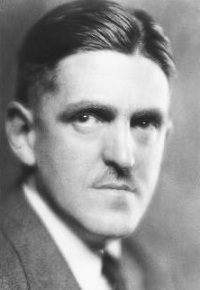

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse

1877-1962

Hermann Hesse was born on July 2, 1877, in Calw, Wurttemberg. Hesse lived in Basel beginning in 1904, after having dropped out of the seminary at the Maulbronn monastery and finishing his training as a book dealer. In Gaienhofen am Bodensee, he worked as a professional writer and for many newspapers.

The novels Peter Camenzind (1904) and Unterm Rad (Beneath the Wheel; English title: The Prodigy, 1906) belong to the first publications in his extensive catalog of creative works. In these works, Hesse thematized the conflict between intellect and nature, a theme that pervades his whole catalog. He left Germany in 1912 and resettled in Bern; from 1914 to 1919, he composed numerous political essays and open letters against the war that were published in many German and Swiss newspapers.

Hesse, who had become a Swiss citizen in 1923, was a foreign member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts from 1926 until 1931. He moved to Montagola in 1931, where he lived and worked until the end of his life. His works were considered objectionable in Germany during the years of World War II.

Hesse received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946 and the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 1955. Besides his numerous poems, stories, essays and treatises, Hesse’s literary fame comes mainly from his novels, which include Demian (1919), Siddarta (1922), Der Steppenwolf (1927), Narziss und Goldmund (1930) and Das Glasperlenspiel (The Glass Bead Game, 1943).

His prose, as well as his poetry, which tend to be nostalgic, often maudlin and folksong-like, show Hesse as a epigonal-harmonizing descendent of the Romantics.

Hesse died on August 9, 1962, in Montagola, Switzerland.

Source: http://www.hesse-hermann.com/

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Heywood

John Heywood

1497-1580

John Heywood, English dramatist and epigrammatist, is generally said to have been a native of North Mimms, near St. Albans, Hertfordshire, though Bale says he was born in London. A letter from a John Heywood, who may fairly be identified with him, is dated from Malines in 1575, when he called himself an old man of 78, which would fix his birth in 1497. He was a chorister of the Chapel Royal and is said to have been educated at Broadgates Hall (Pembroke College), Oxford. From 1521 onward, his name appears in the king’s accounts as the recipient of an annuity of 10 marks as player of the virginals; in 1538, he received 40 shillings for “playing an interlude with his children” before the Princess Mary.

He is said to have owed his introduction to the princess to Sir Thomas More, at whose seat at Gobions, near St. Albans, he wrote his epigrams, according to Henry Peacham. More took a keen interest in the drama and is represented by tradition as stepping onto the stage to take an impromptu part in the dialogue. His skill in music and his inexhaustible wit made him a favorite both with Henry VIII and Mary. Under Edward VI, he was accused of denying the king’s supremacy over the church and had to make a public recantation in 1554; but, with the accession of Mary, his prospects brightened. He made a Latin speech to her in St. Paul’s Churchyard at her coronation and wrote a poem to celebrate her marriage. Shortly before her death, she granted him the lease of a manor and lands in Yorkshire. When Elizabeth succeeded to the throne, Heywood fled to Malines and is said to have returned in 1577. In 1587, he is spoken of as “dead and gone” in Thomas Newton’s epilogue to his works.

Heywood is important in the history of English drama as the first writer to turn the abstract characters of the morality plays into real persons. His interludes link the morality plays to the modern drama and were very popular in their day.

Heywood’s other works are: a collection of proverbs and epigrams, the earliest extant edition of which is dated 1562; some ballads, one of them being the “Willow Garland,” known to Desdemona; and a long verse allegory of more than 7,000 lines, “The Spider and the Flie” (1556).

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/heywoodbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Heywood

Thomas Heywood

1573-1641

It is probable that Thomas Heywood was born about 1575 in Lincolnshire. He was educated at Cambridge and became a fellow of Peterhouse. During his residence at the University, he became deeply interested in the stage and doubtless contributed to the “tragedies, comedies, histories, pastorals and shows” that he tells us were acted in his time by “graduates of good place.”

In 1596, he came to London and wrote a play for the Lord Admiral’s Company, to which in 1598 we find him regularly attached as an actor. Of the dramas he composed at this time, The Four Prentices of London is probably the only one that survives. We have, however, a series of tame chronicle-plays that seem to date from 1600.

Heywood’s masterpiece, A Woman Killed with Kindness, was produced in 1602 (printed in 1607). In the very interesting preface to The English Traveller, which was not published until 1633, Heywood tells us that this tragicomedy is but “one reserved amongst two hundred and twenty, in which I have had either an entire hand or at the least a main finger.” Even at that date, many of these plays had “been negligently lost” and Heywood adds that “it never was any great ambition in me to be in this kind voluminously read.” Of his vast body of dramatic writing, therefore, we may be surprised that so many as 24 complete plays have come down to us.

Of his more ambitious but less successful nondramatic works, Troja Britannica was published in 1609; Gunaikeion, or Nine Books Concerning Women in 1624; and The Hierarchy of the Blessed Angels in 1635.

He disappears from the public record after 1641.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/heywood/heywoodbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

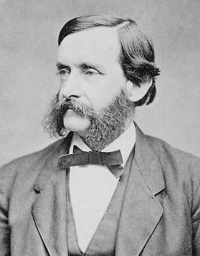

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

1923-1911

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823-May 9, 1911) was an American Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist and soldier. He was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, attended Harvard College at age 13 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa at 16. He graduated in 1841 and was a schoolmaster for two years.

He then studied theology at the Harvard Divinity School. At the end of his first year of divinity training, he withdrew from the school to turn his attention to the abolitionist cause. He spent the subsequent year studying and, following the lead of Transcendentalist minister Theodore Parker, fighting against the expected war with Mexico. Believing that war was only an excuse to expand slavery and the slave power, Higginson wrote anti-war poems and went door-to-door to get signatures for anti-war petitions.

A year after leaving school, a growing passion for abolitionism led Higginson to recommence his divinity studies and he graduated in 1847. Higginson was called as pastor at the First Religious Society of Newburyport, Massachusetts, a Unitarian church known for its liberal Christianity. He supported the Essex County Antislavery Society and criticized the poor treatment of workers at Newburyport cotton factories. In addition, the young minister invited Theodore Parker, Ralph Waldo Emerson and fugitive slave William Wells Brown to speak at the church; in sermons, he condemned Northern apathy toward slavery. Higginson proved too radical for the congregation and was forced to resign in 1848.

In 1852, Higginson became pastor of the Free Church in Worcester. During his tenure, Higginson not only supported abolition but also temperance, labor rights and the rights of women.

During the early part of the Civil War, Higginson was a captain in the 51st Massachusetts Infantry. From November 1862 to October 1864, when he was retired because of a wound received in the preceding August, he was colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first authorized regiment recruited from freedmen for the Federal service. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton required that black regiments be commanded by white officers. Higginson described his Civil War experiences in Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870). He contributed to the preservation of Negro spirituals by copying dialect verses and music he heard sung around the regiment’s campfires.

After the Civil War, he devoted most of his time to literature. His writings show a deep love of nature, art and humanity and are marked by vigor of thought, sincerity of feeling and grace and finish of style. In his Common Sense about Women (1881) and his Women and Men (1888), he advocated equality of opportunity and equality of rights for the two sexes.

In 1891, Higginson became one of the founders of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom (SAFRF) and edited its public appeal, “To the Friends of Russian Freedom.” Later, in 1907, Higginson was the vice president of the SAFRF.

Higginson died May 9, 1911.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wentworth_Higginson

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Tomson Highway

Tomson Highway

1951-

Tomson Highway (born December 5, 1951) is a celebrated Canadian and Cree playwright, novelist and children’s author. He is the author of the plays, The Rez Sisters and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, both of which won him the Dora Mavor Moore Award and the Floyd S. Chalmers Award.

Highway has also published a novel, Kiss of the Fur Queen (1998), which is based on the events that led to his brother Rene Highway’s death of AIDS. He also has the distinction of being the librettist of the first Cree-language opera, The Journey or Pimooteewin.

Highway was born in Brochet, Manitoba, in 1951 to Pelagie Highway, a bead-worker and quilt-maker, and Joe Highway, a caribou hunter and champion dogsled racer. From age six to 15, he attended Guy Hill Indian Residential School, where he was sexually abused by the priests who ran the school. This deeply affected Highway’s later work.

He obtained his B.A. in Music Honors in 1975 and his B.A. in English in 1976, both from the University of Western Ontario. For seven years, Highway worked as a social worker on reserves across Ontario and Canada. Subsequently, he turned the knowledge and experience gained by working in these places into novels and plays that have won him widespread recognition across Canada and around the world.

In 1986, he published the multiple-award-winning play, The Rez Sisters. In 1989, he published Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing.

He was artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto from 1986 to 1992, as well as serving with the De-ba-jeh-mu-jig theatre group in Wikwemikong.

Frustrated with difficulties presented by play production, Highway turned his focus to a novel, Kiss of the Fur Queen.

After a 10-year hiatus from playwriting, Highway wrote Ernestine Shuswap Gets Her Trout in 2005.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomson_Highway

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

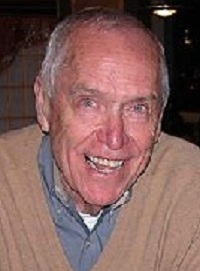

Tony Hillerman

Tony Hillerman

1925-2008

Tony Hillerman (May 27, 1925-October 26, 2008) was an award-winning American author of detective novels and nonfiction works, best known for his Navajo Tribal Police mystery novels. Several of his works have been adapted as big-screen and television movies.

Hillerman died on October 26, 2008, of pulmonary failure in Albuquerque at the age of 83.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Hillerman

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Rolando Hinojosa-Smith

Rolando Hinojosa-Smith

1929-2022

Rolando Hinojosa (born 1929) was a novelist, essayist, poet and the Ellen Clayton Garwood professor in the English Department at the University of Texas at Austin.

He was born in Texas’ Lower Rio Grande Valley to a family with strong Mexican and American roots; his father fought in the Mexican Revolution, while his mother maintained the family north of the border. An avid reader during childhood, Hinojosa was raised speaking Spanish until junior high, where English was the primary spoken language. Like his grandmother, mother and three of his four siblings, Hinojosa became a teacher; he has held several academic posts and has also been active in administration and consulting work.

Hinojosa devoted most of his career as a writer to his Klail City Death Trip series, which comprises 15 volumes, from Estampas del Valle y otras obras (1973) to We Happy Few (2006). He completely populated a fictional county in the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas through this generational narrative. Although he preferred to write in Spanish, Hinojosa also translated his own books and wrote others in English.

Hinojosa was the first Chicano author to receive the prestigious Premio Casa de las Americas award for Klail City y sus alrededores (Klail City), part of the series. He also received the third and final Premio Quinto Sol Annual Prize (1972) for his work, Estampas del Valle y otras obras.

Hinojosa died on April 19, 2022 in Cedar Park, Texas.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rolando_Hinojosa

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

S.E. Hinton

S.E. Hinton

1950-

Susan Eloise Hinton (born July 22, 1950) is an American author best known for her young adult novel, The Outsiders.

While still in her teens, Hinton became a household name as the author of The Outsiders, her first and most popular novel, set in Oklahoma in the 1960s. She began writing it in 1965 and it was published in 1967 during her freshman year at the University of Tulsa.

Hinton’s publisher suggested she use her initials instead of her feminine given names so that the very first male book reviewers would not dismiss the novel because its author was female. After the success of The Outsiders, Hinton chose to continue writing and publishing using her initials, both because she did not want to lose what she had made famous and to allow her to keep her private and public lives separate.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S._E._Hinton

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Minfong Ho

Minfong Ho

1951-

Minfong Ho is an award-winning Chinese-American writer. Her works frequently deal with the lives of people living in poverty in Southeast Asian countries. Despite being fictions, her stories are always set against the backdrop of real events, such as the student movement in Thailand in the 1970s and the Cambodian refugee problem with the collapse of Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s and 1980s.

Ho was born in Rangoon, Burma, better known now as Yangon, Myanmar, to an economist father and chemist mother, who were both of Chinese descent. Ho was raised in Thailand, near Bangkok, where she attended the Patana School and the International School, Bangkok. She was enrolled in Tunghai University in Taiwan and subsequently transferred to Cornell University in the United States, where she attained her bachelor’s degree in economics.

It was in Cornell when she first began to write to combat homesickness. She submitted a short story, “Sing to the Dawn,” to the Council for Interracial Books for Children for its annual short story contest. She won the award for the Asian-American Division of unpublished Third World Authors and was encouraged to enlarge the story into a novel.

In Sing to the Dawn, Ho brought her readers into a realistic rural Thailand through the eyes of a young village girl, Dawan, whose struggle to convince those around her to allow her to take up a scholarship to study in the city reflected the sexual discrimination faced by girls in Thailand, especially in the countryside.

After marrying John Value Dennis Jr., an international agriculture policy worker she met during her Cornell years, Ho completed a master’s degree in creative writing while working as an English literature teaching assistant. In 1986, she began writing fiction again. The result was Rice without Rain. Five years later, Ho published her third book, The Clay Marble.

In 1983, Ho returned to Singapore, where she worked as the writer-in-residence at the National University of Singapore for the next seven years. After the birth of her third and last child, Ho shifted her focus to writing books for children. Collaborating with Saphan Ros, executive director of the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia, she published two books on traditional Cambodian folktales, The Two Brothers and Brother Rabbit: A Cambodian Tale. In the meantime, she translated 16 Tang poems into English and compiled them into a picture book, Maples in the Mist: Children’s Poems from the Tang Dynasty. In 2004, she returned to writing for more mature readers with Gathering the Dew.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minfong_Ho

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

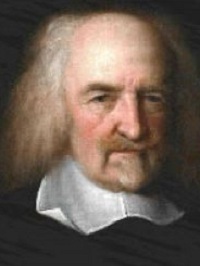

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

1588-1679

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury (April 5, 1588-December 4, 1679), in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was born at Westport, now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England. He was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy. His 1651 book, Leviathan, established the foundation for most of Western political philosophy from the perspective of social contract theory.

Hobbes was a champion of absolutism for the sovereign but he also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: The right of the individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state); the view that all legitimate political power must be “representative” and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal interpretation of law that leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.

One of the founders of modern political philosophy, his understanding of humans as being matter and motion, obeying the same physical laws as other matter and motion, remains influential. His account of human nature as self-interested cooperation, and of political communities as being based upon a “social contract,” remains one of the major topics of political philosophy.

In addition to political philosophy, Hobbes contributed to a diverse array of other fields, including history, geometry, the physics of gases, theology, ethics and general philosophy.

In October 1679, Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, which was followed by a paralytic stroke from which he died on December 4, 1679.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hobbes

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Will Hobbs

Will Hobbs

1947-

William Carl Hobbs grew up in an Air Force family and was raised in Panama, Virginia, Alaska, northern California, southern California and Texas. He was the middle child of five born to Mary Ann (Rhodes) Hobbs and Gregory J. Hobbs.

“During the years we were living in Alaska,” Hobbs has written, “I fell in love with mountains, rivers, fishing, baseball, and books.”

He graduated from Stanford University with a B.A. in English in 1969. His M.A. in English from Stanford followed in 1971. He and his wife, Jean, were married in December, 1972. Drawn by the San Juan Mountains to southwestern Colorado, they found teaching jobs in Pagosa Springs. After four years they resettled in the Durango area, where Hobbs taught for 10 years at Miller Junior High. Summers he devoted to writing, backpacking and rowing his whitewater raft through the canyons of the Southwest. Hobbs rowed 10 trips down the Grand Canyon. In 1990 he began writing full-time.

His professional travels have taken him to 47 states, Canada, and Germany, where six of his novels have been published in the German language. Other foreign editions have appeared in Sweden, the Czech Republic, Italy, the Netherlands, and the U.K.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will_Hobbs

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Sir Thomas Hoby

Sir Thomas Hoby

1530-1566

Sir Thomas Hoby (1530-1566) was an English diplomat and translator. He was born in 1530, the second son of William Hoby of Leominster, Herefordshire, by his second wife, Katherine, daughter of John Forden. He matriculated at St. John’s College, Cambridge, in 1546. Encouraged by his sophisticated half-brother, Sir Philip Hoby, he subsequently visited France, Italy and other foreign countries. His tour of Italy, which included visits to Calabria and Sicily and which he documented in his autobiography, is the most extensive known to have been undertaken by an Englishman in the 16th century. In this and other respects, it may be regarded as a pioneering Grand Tour.

Hoby translated Martin Bucer’s Gratulation to the Church of England (1549) and Baldassare Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano (1561). The latter translation of The Courtier, entitled The Courtyer of Count Baldessar Castilio, had great popularity and was one of the key books of the English Renaissance. It provided a philosophy of life for the Elizabethan-era gentleman. A reading of its pages fitted him for the full assimilation of the elaborate refinements of the new Renaissance society. It furnished his imagination with the symbol of a completely developed individual, an individual who united ethical theory with spontaneity and richness of character.

On March 9, 1566 he was knighted at Greenwich and was sent as ambassador to France at the end of the month. At the time of his landing in Calais, on April 9, a soldier at the town gate shot through the English flag in two places. Hoby demanded redress for the insult and obtained it after some delay, but he was not permitted to view the new fortifications. He died at Paris on July 13, 1566, and was buried at Bisham, Berkshire, where his widow erected a monument to his memory and to that of his half-brother, Sir Philip Hoby.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hoby

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Hoccleve

Thomas Hoccleve

1368-1426

Thomas Hoccleve or Occleve (c. 1368-1426) was an English poet and clerk.

Hoccleve is thought to have been born in 1368/69 as he states when writing, in 1421/22, that he has seen “fifty wyntir and three.” Nothing is known of his family, but his name may come from the village of Hockliffe in Bedfordshire. What is known of his life is gleaned mainly from his works and from administrative records. He obtained a clerkship in the Office of the Privy Seal at the age of about 20. This would require him to know French and Latin. He retained the post on and off, in spite of much grumbling, for about 35 years. He had hoped for a church benefice, but none came. On November 12, 1399, however, he was granted an annuity by the new king, Henry IV.

“The Letter to Cupid,” the first poem of his which can be dated, was a 1402 translation of “L’Epistre au Dieu d’Amours of Christine de Pisan,” written as a sort of riposte to the moral of “Troilus and Criseyde,” to some manuscripts of which it is attached. “La Male Regle” (c. 1406), one of his most fluid and lively poems, is a mock-penitential poem that gives some interesting glimpses of dissipation in his youth.

By 1410, he had married “only for love” and settled down to writing moral and religious poems. His best-known poem, “Regement of Princes, or De Regimine Principum,” written for Henry V of England shortly before his accession, is an elaborate homily on virtues and vices and a work of Jacques de Cessoles translated later by Caxton as “The Game and Playe of Chesse.”

A period of “wylde infirmitee,” in which he temporarily lost his “wit” and “memorie,” is mentioned in one of his poems. He recovered from this “five years ago last All Saints” – November 1, 1414. His “Dialog with a Friend,” written after his recovery, gives a pathetic picture of a poor poet, now 53, with sight and mind impaired but with hopes still left of writing a tale he owes his good patron, Humphrey of Gloucester, and of translating a small Latin treatise, “Scite Mori,” before he dies. His hopes were fulfilled in his moralized tales, “Jereslau’s Wife” and “Jonathas,” both from the “Gesta Romanorum” which, with “Learn to Die,” belong to his old age.

In addition to writing his own poetry, Hoccleve seems to have supplemented the income from his Privy Seal clerkship by working as a scribe. He also compiled a formulary of more than a thousand model Privy Seal documents in French and Latin for the use of other clerks.

On March 4, 1426, the Exchequer issue rolls record a last reimbursement to Hoccleve (for red wax and ink for office use). He died soon after.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hoccleve

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Eva Hoffman

Eva Hoffman

1945-

Eva Hoffman (born Ewa Wydra on July 1, 1945, Cracow, Poland) is a writer and academic.

She was born in Poland after her Jewish parents survived the Holocaust by hiding in Ukraine. In 1959, during the Cold War, the 13-year-old Ewa, her nine-year-old sister, Alinka and her parents immigrated to Vancouver, Canada, where her name was changed to Eva. Upon graduating from high school, she received a scholarship and studied English literature at Rice University, Texas, in 1966, the Yale School of Music (1967-68) and Harvard University, where she received a Ph.D in English and American literature in 1974.

Hoffmann has been a professor of literature and creative writing at various institutions, such as Columbia University, the University of Minnesota, Tufts and CUNY’s Hunter College. From 1979 to 1990, she worked as an editor and writer at The New York Times, serving as senior editor of The Book Review from 1987 to 1990. In 1990, she received the Jean Stein Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and, in 1992, the Guggenheim Fellowship for General Nonfiction, as well as the Whiting Writers’ Award. In 2000, Hoffman was the Year 2000 Una Lecturer at the Townsend Center for the Humanities at the University of California, Berkeley. In 2008, she was awarded an honorary D.Litt by the University of Warwick.

She now lives in London.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eva_Hoffman

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

E.T.A. Hoffmann

E.T.A. Hoffmann

1776-1822

Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann (January 24, 1776-June 25, 1822), better known by his pen name E.T.A. Hoffmann, was born in Konigsberg, Prussia. He studied law at the University of Konigsberg and, by 1800, he had become a court official with the Prussian government in Berlin. However, in 1802, he was forced to move to the Polish town of Plock, partly because he had drawn an uncomplimentary sketch of one of his superiors. He obtained an appointment to Warsaw in 1804 and there wrote music until 1806, when he lost his government position during Napoleon’s occupation of Prussia.

During the next few years, Hoffmann cultivated his talents as writer, artist and composer. By 1808, he had become orchestra conductor for the theater in Bamberg. Here, he began to write the first of his short stories. His first published collection was Fantasiestucke in Callots Manier (1814-15; Phantasies in the Fashion of Callot), inspired by a French painter of grotesques. One of the best in this collection is “Der goldne Topf” (“The Golden Pot”), which tells of a law student torn between the love of a demonic “serpent-girl” and the daughter of a bureaucratic official. In the end, the forces of the supernatural win out.

Hoffmann continued his career as musical director, moving to Dresden and, in 1814, to Berlin, where he associated with other romantic writers, such as the poet Clemens Brentano. He was eventually reinstated as an official in the Prussian government and, in 1816, he became a judge with the superior court. He continued his literary activity, however, and in 1815-16 published a horror novel, Die Elixiere des Teufels (The Devil’s Elixir). This tale, inspired by the English Gothic novel, recounts in lurid detail a wicked monk’s commerce with evil spirits. Another grotesque novel is Lebens-Ansichten des Katers Murr (1820-22; Views on Life of Tomcat Murr).

Hoffmann continued to serve as judge until the year of his death, relatively unhampered by a capacity for alcohol that is thought to have been a source of some of his more striking literary inspirations.

He died on June 25, 1822, in Berlin, of a spinal infection.

Source: http://www.answers.com/topic/e-t-a-hoffmann

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

James Hogg

James Hogg

1770-1835

James Hogg (1770-November 21, 1835) was a Scottish poet and novelist who wrote in both Scots and English. He was born in a small farm near Ettrick, Scotland, in 1770 and was baptized there on December 9, his actual date of birth having never been recorded. His father, Robert Hogg (1729-1820), was a tenant farmer while his mother, Margaret Hogg (nee Laidlaw) (1730-1813), was noted for collecting native Scottish ballads.

Hogg had little formal education and became a shepherd, living in grinding poverty, hence his nickname, “The Ettrick Shepherd.” His employer, James Laidlaw of Blackhouse in the Yarrow valley, seeing how hard he was working to improve himself, offered to help by making books available. Hogg used these to essentially teach himself to read and write (something he had achieved by the age of 14).

In 1801, Hogg visited Edinburgh for the first time. His first collection, The Mountain Bard, was published in 1807 but he struggled to make an impact on the literary scene. Another venture, a magazine called The Spy, failed after a year. But his epic story-poem, “The Queen’s Wake,” was published in 1813 and was a success. Now a well-known literary figure, he was recruited by William Blackwood for Blackwood’s Magazine.

It was through Blackwood’s that Hogg found fame, although it was not the sort that he wanted. Launched as a counter-blast to the Whig Edinburgh Review, Blackwood wanted punchy content in his new publication. He found his ideal contributors in John Wilson (who wrote as Christopher North) and John Gibson Lockhart. Their first published article, “The Chaldee Manuscript,” a thinly disguised satire of Edinburgh society in biblical language that Hogg started and Wilson and Lockhart elaborated, was so controversial that Wilson fled and Blackwood was forced to apologize. Soon, Blackwood’s Tory views and reviews – often scurrilous attacks on other writers – were notorious and the magazine had become one of the best-selling journals of its day. But Hogg quickly found himself forced out of the inner circle. Wilson and Lockhart were dangerous friends.

Hogg’s Memoirs of the Author’s Life was savagely attacked by an anonymous reviewer, probably Wilson, and in 1822 the magazine launched the “Noctes Ambrosianae” or “Ambrosian Nights,” imaginary conversations in a drinking den between semi-fictional characters such as North, O’Doherty, The Opium Eater and the Ettrick Shepherd (Hogg). The Noctes continued until 1834 and were written after 1825, mostly by Wilson, although other writers, including Hogg himself, had a hand in them.

In 1824, no longer highly regarded in Edinburgh, largely excluded from Blackwood’s, now in his 50s but with a young family and writing desperately quickly for money to try to save his failing farm, Hogg wrote his famous tale of persecution, delusion, devilish mimicry and tortured consciousness: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Hogg

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Holcroft

Thomas Holcroft

1745-1809

Thomas Holcroft (December 10, 1745-March 23, 1809) was an English dramatist and miscellaneous writer. He was born in Orange Court, Leicester Fields, London. His father had a shoemaker’s shop and kept riding horses for hire but, having fallen into difficulties, was reduced to the status of hawking pedlar. The son accompanied his parents in their travels and obtained work as a stable boy at Newmarket, where he spent his evenings chiefly in miscellaneous reading and the study of music. Gradually, he obtained a knowledge of French, German and Italian.

When his job as stable boy came to an end, Holcroft returned to assist his father, who had resumed his trade of shoemaker in London; but, after marrying in 1765, he became a teacher in a small school in Liverpool. He failed in an attempt to set up a private school and became prompter in a Dublin theatre. He acted in various strolling companies until 1778, when he produced The Crisis; or Love and Famine, at Drury Lane. Duplicity followed in 1781.

Two years later, he went to Paris as correspondent of The Morning Herald. Here, he attended the performances of Beaumarchais’ Mariage de Figaro until he had memorized the whole. The translation of it, with the title The Follies of the Day, was produced at Drury Lane in 1784. The Road to Ruin, his most successful melodrama, was produced in 1792. A revival in 1873 ran for 118 nights.

He was a member of the Society for Constitutional Information and, as a result, was indicted in 1794 of high treason but was discharged without a trial. Among his novels are Alwyn (1780), an account, largely autobiographical, of a strolling comedian, and Hugh Trevor (1794-97). He also was the author of Travels from Hamburg through Westphalia, Holland and the Netherlands to Paris, of some volumes of verse and of translations from French and German.

His Memoirs written by Himself and continued down to the Time of his Death, from his Diary, Notes and other Papers, by William Hazlitt, appeared in 1816, and was reprinted, in a slightly abridged form, in 1852.

Source: http://www.knowledgerush.com/kr/biography/2067/Thomas_Holcroft/

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

1809-1894

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (August 29, 1809-October 7, 1894) was an American physician, professor, lecturer and author. Regarded by his peers as one of the best writers of the 19th century, he is considered a member of the Fireside Poets. His most famous prose works are the Breakfast-Table series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He is recognized as an important medical reformer.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Holmes was educated at Phillips Academy and Harvard College. After graduating from Harvard in 1829, he briefly studied law before turning to the medical profession. He began writing poetry at an early age; one of his most famous works, “Old Ironsides,” was published in 1830. Following training at the prestigious medical schools of Paris, Holmes was granted his M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1836. He taught at Dartmouth Medical School before returning to teach at Harvard and, for a time, served as dean there. During his long professorship, he became an advocate for various medical reforms and notably posited the controversial idea that doctors were capable of carrying puerperal fever from patient to patient. Holmes retired from Harvard in 1882 and continued writing poetry, novels and essays until his death in 1894.

Surrounded by Boston’s literary elite – which included friends such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell – Holmes made an indelible imprint on the literary world of the 19th century. Many of his works were published in The Atlantic Monthly, a magazine that he named. For his literary achievements and other accomplishments, he was awarded numerous honorary degrees from universities around the world. Holmes’ writing often commemorated his native Boston area and much of it was meant to be humorous or conversational.

Some of his medical writings, notably his 1843 essay regarding the contagiousness of puerperal fever, were considered innovative for their time. He was often called upon to issue occasional poetry, or poems written specifically for an event, including many occasions at Harvard. Holmes also popularized several terms, including “Boston Brahmin” and “anesthesia.”

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Wendell_Holmes,_Sr.#Writing

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

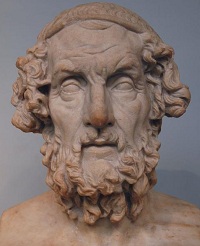

Homer

Homer

1100-1200 BC

In the Western classical tradition, Homer is the author of The Iliad and The Odyssey and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.

When he lived is controversial. Herodotus estimates that Homer lived 400 years before Herodotus’ own time, which would place him at around 850 BC, while other ancient sources claim that he lived much nearer to the supposed time of the Trojan War, in the early 12th century BC.

For modern scholars, “the date of Homer” refers not to an individual, but to the period when the epics were created. The consensus is that “The Iliad and The Odyssey date from around the 8th century BC, The Iliad being composed before The Odyssey, perhaps by some decades,” i.e. earlier than Hesiod, the Iliad being the oldest work of Western literature.

The question of the historicity of Homer the individual is known as the “Homeric question;” there is no reliable biographical information handed down from classical antiquity. The poems are generally seen as the culmination of many generations of oral storytelling in a tradition with a well-developed formulaic system of poetic composition.

The formative influence played by the Homeric epics in shaping Greek culture was widely recognized and Homer was described as the teacher of Greece. Homer’s works, which are about 50 percent speeches, provided models in persuasive speaking and writing that were emulated throughout the ancient and medieval Greek worlds. Fragments of Homer account for nearly half of all identifiable Greek literary papyrus finds.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homer

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Hone

William Hone

1780-1842

William Hone (June 3, 1780-November 8, 1842) was an English writer, satirist and bookseller. His victorious court battle against government censorship in 1817 marked a turning point in the fight for British press freedom.

Hone was born at Bath and had a strict religious upbringing. The only education he received was to be taught to read from the Bible. His father moved to London in 1783 and, in 1790, Hone was placed in an attorney’s office. After two and a half years in the office of a solicitor at Chatham, he returned to London to become clerk to a solicitor at Gray’s Inn. But he disliked the law and had learned to think for himself. To the great concern of his father, he joined the London Corresponding Society in 1796, which campaigned to extend the vote to working men and was deeply unpopular with the government, which had tried to charge its leaders with treason.

Hone married in 1800 and started a book and print shop with a circulating library in Lambeth Walk. He soon moved to St. Martin’s Churchyard, where he brought out his first publication, Shaw’s Gardener (1806).

In 1811, Hone was employed by the booksellers as auctioneer to the trade and had an office in Ivy Lane. Independent investigations carried on by him into the condition of lunatic asylums led again to business difficulties and failure, but he took a small lodging in the Old Bailey, keeping himself and his now-large family by contributions to magazines and reviews. In 1815, he started The Traveller newspaper and tried in vain to save Elizabeth Fenning, a cook convicted on thin evidence of poisoning her employers with arsenic. Although Fenning was executed, Hone’s 240-page book on the subject, The Important Results of an Elaborate Investigation into the Mysterious Case of Eliza Fenning – a landmark in investigative journalism – demolished the prosecution’s case.

Among Hone’s most successful political satires were The Political House that Jack Built (1819), The Queen’s Matrimonial Ladder (1820), Ill Favour of Queen Caroline, The Man in the Moon (1820) and The Political Showman (1821). Many of his squibs are directed against a certain “Dr. Slop,” a nickname given by him to Dr. (afterward Sir John) Stoddart, publisher of The Times. In researches, he had come upon some curious and at that time little-trodden literary ground. The results were shown by his publication in 1820 of his Apocryphal New Testament and, in 1823, of his Ancient Mysteries Explained. In 1826, he published The Every-day Book; in 1827-28, The Table-Book; and, in 1829, The Year-Book. All three were collections of curious information on manners, antiquities and various other subjects.

He died at Tottenham in 1842.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Hone

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood

1799-1845

Thomas Hood (May 23, 1799-May 3, 1845) was a British humorist and poet. He was born in London to Thomas Hood and Elizabeth Sands in the Poultry, Cheapside, above his father’s bookshop. Hood’s paternal family had been Scottish farmers from the village of Errol near Dundee.

Hood left his private school at 14 years of age and was admitted soon after into the counting house of a friend of his family. Eventually moving to Dundee, Hood made a number of close friends with whom he continue to correspond for many years, led a healthy outdoor life and also became a large and indiscriminate reader. It was also during his time here that Hood began to seriously write poetry and published his first work, a letter to the editor of The Dundee Advertiser.

Before long, Hood contributed humorous and poetical articles to the provincial newspapers and magazines. In 1821, John Scott, the editor of The London Magazine, was killed in a duel and the periodical passed into the hands of some friends of Hood, who proposed to make him sub-editor. His installation into this post at once introduced him to the literary society of the time. In becoming the associate of John Hamilton Reynolds, Charles Lamb, Henry Cary, Thomas de Quincey, Allan Cunningham, Bryan Procter, Serjeant Talfourd, Hartley Coleridge, the peasant-poet John Clare and other contributors to the magazine, he gradually developed his own powers.

In 1824, his first work, Odes and Addresses, was written in conjunction with his brother-in-law, J.H. Reynolds. The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies (1827) and a dramatic romance, “Lamia,” published later, belong to this time. The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies was a volume of serious verse – but Hood was known as a humorist and the public rejected this little book almost entirely.

The series of the Comic Annual, dating from 1830, was a kind of publication at that time popular, which Hood undertook and continued, almost unassisted, for several years. Under that somewhat frivolous title, he treated all the leading events of the day in caricature, without personal malice and with an undercurrent of sympathy.

From his sick-bed, from which he never rose, he continued his work and there composed well-known poems, such as “The Song of the Shirt” and “The Bridge of Sighs.”

Hood died in May 1845.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hood

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Richard Hooker

Richard Hooker

1554-1600

Richard Hooker was born in March 1554 in Exeter. He was educated in Exeter until he was sent, with Bishop Jewel as his patron, to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He graduated M.A. in 1577 and became a fellow of the college in the same year. He became assistant professor of Hebrew at the university and took holy orders, becoming a clergyman in the Church of England in 1581. Hooker was Master of the Temple (i.e., Dean of the Law School) in 1585-1591. Thereafter, he lived in London and then at Boscombe, Wiltshire. He died at Bishopsbourne, in Kent, where he had become vicar.

Hooker’s masterpiece is a long work in eight books called Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. The first four books were published together in 1593, the fifth was published in 1597 and the rest appeared after his death. Although the last three volumes were Hooker’s work, they seem to have been heavily edited. The work represents one of the most distinguished examples of Elizabethan literature. King James I is quoted by Izaak Walton, Hooker’s biographer, as saying, “I observe there is in Mr. Hooker no affected language; but a grave, comprehensive, clear manifestation of reason, and that backed with the authority of the Scriptures, the fathers and schoolmen, and with all law both sacred and civil.”

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/hookbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Anthony Hope

Anthony Hope

1863-1933

Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins, better known as Anthony Hope (February 9, 1863-July 8, 1933), was an English novelist and playwright. Although he was a prolific writer, especially of adventure novels, he is remembered best for only two books: The Prisoner of Zenda (1894) and its sequel, Rupert of Hentzau (1898).

Hope was born in Clapton, then on the edge of London, where his father, the Reverend Edward Connerford Hawkins, was headmaster of St. John’s Foundational School for the Sons of Poor Clergy. Hope’s mother was Jane Isabella Grahame. Hope trained as a lawyer and barrister, being called to the Bar by the Middle Temple in 1887. He had time to write, as his working day was not overly full during these first years, and he lived with his widowed father, then vicar of St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street. Hope’s short pieces appeared in periodicals but, for his first book, he resorted to a vanity press. More novels and short stories followed, including Father Stafford in 1891 and Mr. Witt’s Widow in 1892.

In 1893, he wrote three novels (Sport Royal, A Change of Air and Half-a-Hero) and a series of sketches that first appeared in The Westminster Gazette and were collected in 1894 as The Dolly Dialogues. The Prisoner of Zenda was published in 1894. In the same year, Hope also produced The God in the Car. The sequel to Zenda, Rupert of Hentzau, begun in 1895 and serialized in The Pall Mall Magazine, did not appear between hard covers until 1898. A prequel, The Heart of Princess Osra, a collection of short stories set about 150 years before Zenda, appeared in 1896.

Hope wrote 32 volumes of fiction over the course of his lifetime and he had a large popular following. In 1896, he published The Chronicles of Count Antonio, followed in 1897 by a tale of adventure set on a Greek island, entitled Phroso. In 1898, he wrote Simon Dale, an historical novel. One of Hope’s plays, The Adventure of Lady Ursula, was produced in 1898. This was followed by his novel, The King’s Mirror (1899). In 1900, he published Quisante. He wrote Tristram of Blent in 1901 and Double Harness in 1904, followed by A Servant of the Public in 1905. In 1906, he produced Sophy of Kravonia, a novel in a similar vein to Zenda. In 1910, he wrote Second String, followed the next year by Mrs. Maxon Protests.

In addition, Hope wrote or co-wrote many plays and some political nonfiction during the Great War, some under the auspices of the Ministry of Information. Later publications included Beaumaroy Home from the Wars (1919) and Lucinda (1920). He published an autobiographical book, Memories and Notes, in 1927.

Hope died of throat cancer at the age of 70.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Hope

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Laura Lee Hope (Stratemeyer Syndicate)

Laura Lee Hope (Stratemeyer Syndicate)

Laura Lee Hope is a pseudonym used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate for The Bobbsey Twins and several other series of children’s novels. Actual writers taking up the pen of Laura Lee Hope include Edward Stratemeyer, Howard and Lilian Garis, Elizabeth Ward, Harriet (Stratemeyer) Adams, Andrew E. Svenson, June M. Dunn, Grace Grote and Nancy Axelrad.

Laura Lee Hope was first used as a pseudonym in 1904 for the debut of The Bobbsey Twins.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laura_Lee_Hope

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Ellen Hopkins

Ellen Hopkins

1955-

Ellen Hopkins (born March 26, 1955) is a novelist who has published several New York Times bestselling novels that are popular among the teenage and young adult audience.

Hopkins began her writing career in 1990. She started with nonfiction books for children, including Air Devils and Orcas: High Seas Supermen. She has written 56 such nonfiction books.

Hopkins has since written several verse novels exposing teenage struggles such as drug addiction, mental illness and prostitution, including Burned, Impulse, Identical, Glass, Tricks and Fallout. Glass is the sequel to Crank, and Fallout, the third and final book in the series, was released on September 14, 2010. Perfect was released on September 13, 2011, and is a companion novel to Impulse. Hopkins released a sequel to Burned, called Smoke, in 2013.

Her second adult novel, Collateral (2012), is about military deployment and how the families that are left behind are affected. Hopkins wants us to remember that as our men and women return from the Middle East, they come home profoundly changed. Coping with that transformation can be challenging for the soldiers and for their loved ones. This book may help readers open their minds and hearts to the new lifestyles they will be living.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ellen_Hopkins

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Gerard Manley Hopkins

1844-1889

Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J. (July 28, 1844-June 8, 1889) was an English poet, Roman Catholic convert and Jesuit priest whose posthumous 20th century fame established him among the leading Victorian poets.

Hopkins was born in Stratford, East of London, as the first of nine children to Manley and Catherine (Smith) Hopkins. At 10 years old, Hopkins was sent to board at Highgate School (1854-1863) and, while studying Keats’ poetry, composed “The Escorial” (1860), his earliest poem extant. At Balliol College, Oxford (1863-67), he studied classics. He left Oxford in 1879.

Hopkins began his time in Oxford as a keen socialite and prolific poet, but he seemed to have alarmed himself with the changes in his behavior that resulted. He became more studious and began recording his “sins” in his diary. On January 18, 1866, Hopkins composed his most ascetic poem, “The Habit of Perfection.” On January 23, he included poetry in the list of things to be given up for Lent. In July, he decided to become a Catholic and traveled to Birmingham in September to consult the leader of the Oxford converts, John Henry Newman. Newman received him into the Church on October 21, 1866. On May 5, 1868, Hopkins firmly “resolved to be a religious.” Less than a week later, he made a bonfire of his poems and gave up poetry almost entirely for seven years. After his graduation in 1867, Hopkins was provided a teaching post at the Oratory in Birmingham by Newman. He also felt the call to enter the ministry and decided to become a Jesuit.

Hopkins began his novitiate in the Society of Jesus at Manresa House, Roehampton, in September 1868 and moved to St. Mary’s Hall, Stonyhurst, for his philosophical studies in 1870, taking vows of poverty, chastity and obedience on September 8, 1870. Writing would remain something of a concern for him, as he felt that his interest in poetry prevented him from wholly devoting himself to his religion. However, after reading Duns Scotus in 1872, he saw that the two did not necessarily conflict. He continued to write a detailed prose journal between 1868 and 1875. Unable to suppress his desire to describe the natural world, he also wrote music, sketched and, for church occasions, wrote some “verses,” as he called them. He would later write sermons and other religious pieces.

After suffering ill health for several years and bouts of diarrhea, Hopkins died of typhoid fever in 1889.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerard_Manley_Hopkins

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins

1859-1930

Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins (1859-August 13, 1930) was a prominent African-American novelist, journalist, playwright, historian and editor. She is considered a pioneer in her use of the romantic novel to explore social and racial themes. Her work was significantly influenced by W.E.B. Du Bois.

Her first known work, a musical play called Slaves’ Escape; or The Underground Railroad (later revised as Peculiar Sam; or the Underground Railroad), first performed in 1880, is one of the earliest-known literary treatments of slaves escaping to freedom. Her short story, “Talma Gordon,” published in 1900, is often named as the first African-American mystery story. She explored the difficulties faced by African-Americans amid the racist violence of post-Civil War America in her first novel, Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South, published in 1900. She published three serial novels between 1901 and 1903 in the African-American periodical, Colored American Magazine – Hagar’s Daughter: A Story of Southern Caste Prejudice; Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest; and Of One Blood: or the Hidden Self. She sometimes used the pseudonym Sarah A. Allen.

Hopkins spent the remainder of her years working as a stenographer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, from burns sustained in a house fire.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_Hopkins

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus)

Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus)

65 BC-8 BC

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (December 8, 65 BC-November 27, 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: “He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words.”

Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: “As his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings.” Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive.

His career coincided with Rome’s momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian’s right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was “a master of the graceful sidestep”), but for others he was, in John Dryden’s phrase, “a well-mannered court slave.”

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

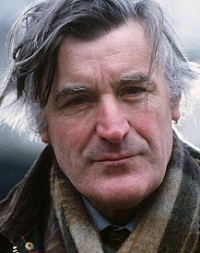

Nick Hornby

Nick Hornby

1957-

Nick Hornby was born in Redhill, Surrey, England. Hornby’s sister, Gill, is married to writer Robert Harris. He was brought up in Maidenhead and was educated at Maidenhead Grammar School and Jesus College, Cambridge.

Hornby’s first published book, 1992’s Fever Pitch, is an autobiographical story detailing his fanatical support for Arsenal Football Club. As a result, Hornby received the William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award. With the book’s success, Hornby began to publish articles in The Sunday Times, Time Out and The Times Literary Supplement, in addition to his music reviews for The New Yorker.

High Fidelity, his second book and first novel, was published in 1995, followed by: About a Boy (1998); How to Be Good (2001); and Speaking with the Angel (2002). He also contributed to the collection with the story, “NippleJesus.”

In 2003, Hornby wrote a collection of essays on selected popular songs and the emotional resonance they carry, called 31 Songs. Also in 2003, Hornby was awarded the London Award 2003, an award that was selected by fellow writers. Hornby has written essays on various aspects of popular culture and, in particular, he has become known for his writing on pop music and mix tape enthusiasts. He also began writing a book review column, Stuff I’ve Been Reading, for the monthly magazine, The Believer, that ran through September 2008; all of these articles are collected between The Polysyllabic Spree (2004), Housekeeping vs. The Dirt (2006) and Shakespeare Wrote for Money (2008).

Hornby’s novel, A Long Way Down, was published in 2005. Slam was released on October 16, 2007.

He released his latest novel, Juliet, Naked, in September 2009.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Hornby

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

E.W. Hornung

E.W. Hornung

1866-1921

Ernest William Hornung (June 7, 1866-March 22, 1921), known as Willie, was an English author, most famous for writing the Raffles series of novels about a gentleman thief in late Victorian London.

Hornung was born in Middlesbrough, England, the third son and youngest of eight children of John Peter Hornung, who was born in Hungary. Ernest Hornung was educated at Uppingham School.

Hornung spent most of his life in England and France but, in December 1883, left for Australia, arrived in 1884 and stayed for two years, working as a tutor at Mossgiel station in the Riverina. Although his Australian experience was brief, it colored most of his literary work – from A Bride from the Bush, published in 1899, to Old Offenders and a few Old Scores, which appeared after his death. Nearly two-thirds of his 30 published novels make reference to Australian incidents and experiences.

Hornung worked as a journalist and also published the poems, “Bond and Free” and “Wooden Crosses,” in The Times. The character of A.J. Raffles, a “gentleman thief,” first appeared in Cassell’s Magazine in 1898 and the stories were later collected as The Amateur Cracksman (1899). Other titles in the series include: The Black Mask (1901), A Thief in the Night (1905) and the full-length novel, Mr. Justice Raffles (1909). He also co-wrote the play, Raffles, The Amateur Cracksman, with Eugene Presbrey in 1903.

After Hornung spent time in the trenches with the troops in France, he published Notes of a Camp-Follower on the Western Front in 1919, a detailed account of his time there.

Hornung died in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, in the south of France, on March 22, 1921.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_William_Hornung

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Khaled Hosseini

Khaled Hosseini

1965-

Khaled Hosseini (born March 4, 1965) is an Afghan-born American novelist and physician. He is a citizen of the United States, where he has lived since he was 15 years old.

Hosseini was born in Kabul, Afghanistan. In 1970, Hosseini and his family moved to Iran, where his father worked for the Embassy of Afghanistan in Tehran.

In 1976, Hosseini’s father obtained a job in Paris, France, and moved the family there. They were unable to return to Afghanistan because of the Saur Revolution in which the PDPA communist party seized power through a bloody coup in April 1978. Instead, in 1980 they sought political asylum in the United States and made their residence in San Jose, California.

Hosseini graduated from Independence High School in San Jose in 1984 and enrolled at Santa Clara University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology in 1988. The following year, he entered the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, where he earned his M.D. in 1993. He completed his residency in internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles in 1996. He practiced medicine for more than 10 years, until a year and a half after the release of The Kite Runner.

His two novels to date are The Kite Runner (2005) and A Thousand Splendid Suns (2007).

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khaled_Hosseini

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

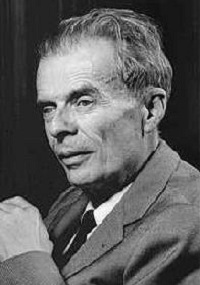

A.E. Housman

A.E. Housman

1859-1936

Alfred Edward Housman (March 26, 1859-April 30, 1936), usually known as A.E. Housman, was an English classical scholar and poet, best known to the general public for his cycle of poems, A Shropshire Lad.

Housman was counted one of the foremost classicists of his age and has been ranked as one of the greatest scholars of all time. He established his reputation publishing as a private scholar and, on the strength and quality of his work, was appointed Professor of Latin at University College London and, later, at Cambridge. His editions of Juvenal, Manilius and Lucan are still considered authoritative.

The eldest of seven children, Housman was born at Valley House in Fockbury, a hamlet on the outskirts of Bromsgrove in Worcestershire, to Sarah Jane (nee Williams) and Edward Housman, and was baptized on April 24, 1859 at Christ Church, in Catshill. In 1877, he won an open scholarship to St. John’s College, Oxford, where he studied classics.

After Oxford, Housman worked as a clerk in the Patent Office in London. Housman continued pursuing classical studies independently and published scholarly articles on such authors as Horace, Propertius, Ovid, Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles.

Although Housman’s early work and his sphere of responsibilities as professor included both Latin and Greek, he began to focus his energy on Latin poetry. In 1911, he took the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he remained for the rest of his life. From 1903-30, he published his critical edition of Manilius’ Astronomicon in five volumes. He also edited works of Juvenal (1905) and Lucan (1926).

Housman died at 77 in Cambridge.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._E._Housman

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Henry Howard (Earl of Surrey)

Henry Howard (Earl of Surrey)

1517-1547

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, was born in Hunsdon, Hertfordshire, in 1517. He was the eldest son of Thomas Howard and Lady Elizabeth Stafford (daughter of the Duke of Buckingham). Surrey was of royal descent on both sides of his family. He was given the title “Earl of Surrey” by courtesy in 1524 on the death of his grandfather, Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey and 2nd Duke of Norfolk, when his father was created 3rd Duke of Norfolk.

In 1532, Surrey accompanied his first cousin, Anne Boleyn, King Henry VIII and the Duke of Richmond to France for a meeting with Francis I. Richmond and Surrey stayed in the French court for nearly a year, as members of the entourage of the French king. Surrey returned to England for the coronation of Anne Boleyn in 1533 and had a position of honor in the ceremonies.

Surrey was a mighty soldier, like his father and grandfather before him, and the Howards had long been loyal to the Tudors. But the Howards were in trouble when Jane Seymour became queen in 1536, and the Seymours, a rival faction at court, began their scheming in earnest. In 1537, the Seymours accused the Howards of sympathizing with the rebels of the Pilgrimage of Grace. Surrey struck a courtier who repeated the slander at court and was imprisoned in Windsor on the order of the privy council. Surrey’s famous poem, “Prisoned in Windsor,” in which he recalls his boyhood days in Windsor, dates from the same year. The accusations were patently false; after all, Surrey and his father had fought to put down the rebellion. He was released later in the year and served as a mourner in Jane Seymour’s funeral.

Surrey served the king in Flanders with the English army on the side of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who was seeking to acquire the Netherlands. In the following year, 1544, Surrey was wounded at the siege of Montreuil and returned to England. He was back in France at the head of a company of 5,000 men in Calais and, in 1545, he became Commander of Guisnes and Commander of the garrison of Boulogne.

When Henry VIII’s health was failing in 1546, Surrey made the mistake of announcing his opinion of the obviousness of his father becoming Protector to young Prince Edward. Arrested along with his father on charges of treason, he was imprisoned in the Tower. Several additional claims were made against him, including that he was secretly a papist. Surrey was indicted of high treason in January 1547, despite the lack of any real evidence, condemned and executed on January 19, 1547 on Tower Hill.

Surrey’s poetry circulated in manuscript form at court. He published his “Epitaph on Sir Thomas Wyatt” but most of his poetry first appeared in 1557, 10 years after his death.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/henrybio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Robert E. Howard

Robert E. Howard

1906-1936

Robert Ervin Howard (January 22, 1906-June 11, 1936) was an American author who wrote pulp fiction in a diverse range of genres. He is regarded as the father of the Sword and Sorcery genre and he created, among other characters, Conan the Cimmerian.

Howard was born and raised in the state of Texas. He spent most of his life in the town of Cross Plains with some time spent in the nearby Brownwood. A bookish and intellectual child, he was also a fan of boxing and spent some time in his late teens bodybuilding, eventually taking up amateur boxing himself. From the age of nine he dreamed of becoming a writer of adventure fiction but did not have real success until he was 23. He was published in a wide selection of magazines, journals and newspapers but his main outlet was the pulp magazine, Weird Tales.

Howard created Conan the Barbarian, in the pages of the Depression-era pulp magazine, Weird Tales, a character whose pop-culture imprint has been compared to such icons as Tarzan, Count Dracula, Sherlock Holmes and James Bond. With Conan and his other heroes, Howard created the genre now known as Sword and Sorcery, spawning a wide swath of imitators and giving him an influence in the fantasy field rivaled only by J.R.R. Tolkien and Tolkien’s similarly inspired creation of High Fantasy. Howard remains a highly read author, with his best work endlessly reprinted. He has been compared to other American masters of the weird, gloomy and spectral, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville and Jack London.

He was successful in several genres and was on the verge of publishing his first novel when he committed suicide at the age of 30. His mother was terminally ill with tuberculosis before she had even met his father and so was slowly dying throughout Howard’s entire life. When he learned that his mother had entered a coma from which she was not expected to wake he, for reasons that are not clear, walked out to his car and shot himself in the head. His suicide and the circumstances surrounding it have led to varied speculation about his mental health; from an Oedipus complex, to clinical depression, to no mental disorders of any kind.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_E._Howard

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Sidney Coe Howard

Sidney Coe Howard

1891-1939

Sidney Coe Howard (June 26, 1891-August 23, 1939) was an American playwright and screenwriter.

Howard was born in Oakland, California, the son of Helen Louise (nee Coe) and John Lawrence Howard. He graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1915 and went on to Harvard University to study the art of playwriting.

A particular admirer of the understated realism of French playwright Charles Vildrac, Howard adapted two of his plays into English: S.S. Tenacity (1929) and Michael Auclair (1932). One of his greatest successes on Broadway was an adaptation of a French comedy by Rene Fauchois, The Late Christopher Bean. In 1921, Howard had his first Broadway production with Swords, followed by They Knew What They Wanted in 1924, which won the 1925 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Other plays included: Lucky Sam McCarver; The Silver Cord (1926); and Yellow Jack (1934).

A prolific writer and founding member of the Playwrights’ Company, he wrote or created more than 70 plays; he also directed and produced a number of works. Hired by Samuel Goldwyn, Howard worked in Hollywood, writing a number of very successful screenplays. In 1932, Howard was nominated for an Academy Award for his adaptation of the Sinclair Lewis novel, Arrowsmith, and, again in 1936, for Dodsworth, which he had adapted for the stage in 1934. Later, Howard wrote the screenplay for Gone with the Wind, for which he won the 1939 Academy Award for Writing-Adapted Screenplay.

A lover of the quiet rural life, Howard died in Tyringham, Massachusetts, while working on his 700-acre hobby farm. Howard was crushed to death by his two-and-a-half ton tractor. He had turned the ignition switch on and was cranking the engine to start it when it lurched forward, pinning him against the wall of the garage. Apparently, an employee had left the transmission in high gear.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Howard

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe

1819-1910

Julia Ward Howe (May 27, 1819-October 17, 1910) was a prominent American abolitionist, social activist and poet most famous as the author of, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Born Julia Ward in New Jersey, she was the fourth of seven children born to Samuel Ward and Julia Rush Cutler. Among her siblings was Samuel Cutler Ward. Her father was a well-to-do banker. Her mother died when she was five. When she was young she learned many languages: Italian, French, German and Greek.

In 1843, she married a hero of the Greek revolution, physician Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, nicknamed Chev, who founded the Perkins Institute for the Blind. The couple made their home in South Boston and were active in the Free Soil Party. She was a member of the Unitarian church. The Howes had five children who lived to adulthood. Her sixth and youngest child died at age 3 from diphtheria.

Howe’s “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” set to William Steffe’s already-existing music, was first published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1862 and quickly became one of the most popular songs of the Union during the American Civil War.

In 1870, Howe was the first to proclaim Mother’s Day with her “Mother’s Day Proclamation.”

After the war, Howe focused her activities on the causes of pacifism and women’s suffrage. From 1872 to 1879, she assisted Lucy Stone and Henry Brown Blackwell in editing Woman’s Journal.

From 1891 to 1909, she was interested in the cause of Russian freedom. Howe supported Russian emigre Stepniak-Kravchinskii and became a member of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom (SAFRF).

Howe died of pneumonia on October 17, 1910, at her home, Oak Glen, in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, at the age of 91. She is buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julia_Ward_Howe#Works_and_collections

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells

1837-1920

William Dean Howells (March 1, 1837-May 11, 1920) was an American realist author and literary critic. Nicknamed “The Dean of American Letters,” he was particularly known for his tenure as editor of The Atlantic Monthly as well as for his own writings, including the Christmas story, “Christmas Every Day,” and the novel, The Rise of Silas Lapham.

Born in Martins Ferry, Ohio, originally Martinsville, to William Cooper and Mary Dean Howells, Howells was the second of eight children. His father was a newspaper editor and printer and moved frequently around Ohio. Howells began to help his father with typesetting and printing work at an early age. In 1852, his father arranged to have one of Howells’ poems published in The Ohio State Journal without telling him.

In 1856, Howells was elected as a clerk in the State House of Representatives. In 1858, he began to work at The Ohio State Journal, where he wrote poetry, short stories and also translated pieces from French, Spanish and German. He avidly studied German and other languages.

Said to be rewarded for a biography of Abraham Lincoln used during the election of 1860, he gained a consulship in Venice. Upon returning to the U.S., Howells wrote for various magazines, including The Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Magazine. In January 1866, James Fields offered him the assistant editor role at The Atlantic Monthly. Howells accepted after successfully negotiating for a higher salary, but was frustrated by Fields’ close supervision. Howells was made editor in 1871, remaining in the position until 1881. In 1869, he first met Mark Twain, which began a longtime friendship. Howells gave a series of 12 lectures on “Italian Poets of Our Century” for the Lowell Institute during its 1870-71 season.

He wrote his first novel, Their Wedding Journey, in 1872, but his literary reputation took off with the realist novel, A Modern Instance, published in 1882, which described the decay of a marriage. His 1885 novel, The Rise of Silas Lapham, is perhaps his best known, describing the rise and fall of an American entrepreneur of the paint business. His social views were also strongly represented in the novels Annie Kilburn (1888), A Hazard of New Fortunes (1890) and An Imperative Duty (1892).

In 1902, Howells bought a summer home overlooking the Piscataqua River in Kittery Point, Maine. He returned there annually until his death. In 1904, he was one of the first seven people chosen for membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters, of which he became president.

Howells died in Manhattan on May 11, 1920.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dean_Howells

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes

1902-1967

James Mercer Langston Hughes, (February 1, 1902-May 22, 1967) was an American poet, novelist, playwright, short story writer and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the new literary art form, jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He is also known for what he wrote about the Harlem Renaissance, “Harlem Was in Vogue.”

Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, the second child of school teacher Carrie (Caroline) Mercer Langston and her husband, James Nathaniel Hughes (1871-1934). Both parents were mixed-race: Hughes was of African-American, European American and Native American descent. He grew up in a series of Midwestern small towns. Both of his paternal great-grandmothers were African-American, and both his paternal great-grandfathers were white: One of Scottish and one of Jewish descent.

Hughes’ father left his family and later divorced Carrie. He went to Cuba, and then Mexico, seeking to escape the enduring racism in the United States. After the separation of his parents, while his mother travelled seeking employment, young Hughes was raised mainly by his maternal grandmother, Mary Patterson Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas. Through the black American oral tradition and drawing from the activist experiences of her generation, Mary Langston instilled in the young Hughes a lasting sense of racial pride.

While in grammar school in Lincoln, Illinois, Hughes was elected class poet. During high school in Cleveland, Ohio, he wrote for the school newspaper, edited the yearbook and began to write his first short stories, poetry and dramatic plays. His first piece of jazz poetry, “When Sue Wears Red,” was written while he was still in high school. It was during this time that he discovered his love of books. From this early period in his life, Hughes would cite as influences on his poetry the American poets Paul Laurence Dunbar and Carl Sandburg.

Hughes worked various odd jobs before serving a brief tenure as a crewman aboard the S.S. Malone in 1923, spending six months traveling to West Africa and Europe. In Europe, Hughes left the S.S. Malone for a temporary stay in Paris.