Author Biographies 6

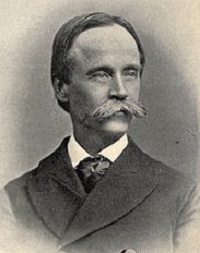

James Branch Cabell

James Branch Cabell

1879-1958

James Branch Cabell (April 14, 1879-May 5, 1958) was an American author of fantasy fiction and belles lettres. During his life, Cabell published 52 books, including novels, genealogies, collections of short stories, poetry and miscellanea. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1937.

Cabell was born into an affluent and well-connected Virginian family and lived most of his life in Richmond. Although Cabell’s surname is often mispronounced “Ka-BELL,” he himself pronounced it “CAB-ble.” To remind an editor of the correct pronunciation, Cabell composed this rhyme: “Tell the rabble my name is Cabell.”

Cabell matriculated to the College of William and Mary in 1894 at the age of 15 and graduated in 1898. While an undergraduate, Cabell taught French and Greek at the College. According to his close friend and fellow author, Ellen Glasgow, Cabell developed a friendship with a professor at the college that was considered by some to be “too intimate” and, as a result, Cabell was dismissed, although he was subsequently readmitted and finished his degree. Following his graduation, he worked from 1898 to 1900 as a newspaper reporter in New York City, but returned to Richmond in 1901, where he worked several months on the staff of The Richmond News.

His first stories were accepted for publication in 1901. In 1902, seven of his first stories appeared in national magazines and over the next decade he wrote many short stories and articles, contributing to nationally published magazines, including Harper’s Monthly Magazine and The Saturday Evening Post, as well as carrying out extensive research on his family’s genealogy.

Cabell died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1958 in Richmond. He is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Branch_Cabell

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

George Washington Cable

George Washington Cable

1844-1925

George Washington Cable (October 12, 1844-January 31, 1925) was an American novelist notable for the realism of his portrayals of Creole life in his native Louisiana. His fiction has been thought to anticipate that of William Faulkner.

Cable was born in New Orleans, Louisiana. He served in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. At the end of the war in 1865, he went into journalism, writing for The New Orleans Picayune, where he would remain through 1879. By that time, he was a well-established writer. His sympathy for civil rights and opposition toward the harsh racism of the era showed in his writings, earning him resentment by many white Southerners. In 1884, Cable moved to Massachusetts. He became friends with Mark Twain and the two writers did speaking tours together.

Cable died in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Washington_Cable

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Caedmon

Caedmon

d. 680

Caedmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. An Anglo-Saxon herdsman attached to the double monastery of Streonaeshalch (Whitby Abbey) during the abbacy of St. Hilda (657-680), he was originally ignorant of “the art of song” but, according to Bede, learned to compose one night in the course of a dream. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational religious poet.

Caedmon is one of 12 Anglo-Saxon poets identified in medieval sources, and one of only three for whom both roughly contemporary biographical information and examples of literary output have survived. His story is related in the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) by St. Bede, who wrote, “[t]here was in the Monastery of this Abbess a certain brother particularly remarkable for the Grace of God, who was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of scripture, he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in English, which was his native language. By his verse the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven.”

Caedmon’s only known surviving work is Caedmon’s Hymn, the nine-line alliterative vernacular praise poem in honor of God that he supposedly learned to sing in his initial dream. The poem is one of the earliest attested examples of Old English and is, with the runic Ruthwell Cross and Franks Casket inscriptions, one of three candidates for the earliest attested example of Old English poetry. It is also one of the earliest recorded examples of sustained poetry in a Germanic language.

After a long and zealously pious life, Caedmon died like a saint: Receiving a premonition of death, he asked to be moved to the abbey’s hospice for the terminally ill where, having gathered his friends around him, he expired just before nocturns. Although he is often listed as a saint, this is not confirmed by Bede and it has recently been argued that such assertions are incorrect.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C%C3%A6dmon

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

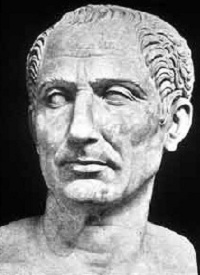

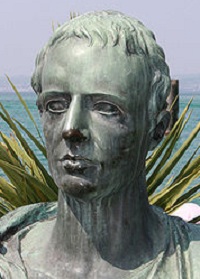

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

100-44 BC

Gaius Julius Caesar (July 100 BC-15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

In 60 BC, Caesar, Crassus and Pompey formed a political alliance that was to dominate Roman politics for several years. Their attempts to amass power through populist tactics were opposed by the conservative elite within the Roman Senate, among them Cato the Younger, with the frequent support of Cicero. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, completed by 51 BC, extended Rome’s territory to the English Channel and the Rhine. Caesar became the first Roman general to cross both when he built a bridge across the Rhine and conducted the first invasion of Britain. These achievements granted him unmatched military power and threatened to eclipse Pompey’s standing. The balance of power was further upset by the death of Crassus in 53 BC. Political realignments in Rome finally led to a standoff between Caesar and Pompey, the latter having taken up the cause of the Senate. Ordered by the Senate to stand trial in Rome for various charges, Caesar marched from Gaul to Italy with his legions, crossing the Rubicon in 49 BC. This sparked a civil war from which he emerged as the unrivaled leader of the Roman world.

After assuming control of government, he began extensive reforms of Roman society and government. He centralized the bureaucracy of the Republic and was eventually proclaimed “dictator in perpetuity.” A group of senators, led by Marcus Junius Brutus, assassinated the dictator on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC, hoping to restore the constitutional government of the Republic. However, the result was a series of civil wars, which ultimately led to the establishment of the permanent Roman Empire by Caesar’s adopted heir, Octavius (later known as Augustus).

Much of Caesar’s life is known from his own accounts of his military campaigns and other contemporary sources, mainly the letters and speeches of Cicero and the historical writings of Sallust. The later biographies of Caesar by Suetonius and Plutarch are also major sources.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Caesar

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

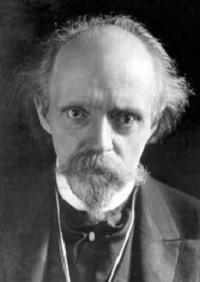

Abraham Cahan

Abraham Cahan

1860-1951

Abraham “Abe” Cahan (July 7, 1860-August 31, 1951) was a Lithuanian-born American socialist newspaper editor, novelist and politician. He was born in Podberezhie, now part of Lithuania but then part of the Russian empire, into an Orthodox Jewish family. His grandfather was a rabbi in Vidz, Vitebsk, his father a teacher of Hebrew language and the Talmud. The family, which was devoutly religious, moved in 1866 to Wilna (Vilnius), where the young Cahan received the usual Jewish preparatory education for the rabbinate. He, however, was attracted by secular knowledge and clandestinely studied the Russian language, ultimately prevailing on his parents to allow him to enter the Teachers Institute of Wilna, from which he was graduated in 1881. He was appointed teacher in a Jewish government school in Velizh, Vitebsk, in the same year.

On March 13, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by terrorist members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Reprisals by the Russian state were quick and massive. A visit from the police prompted the young socialist schoolteacher to escape to the United States through emigration.

Cahan arrived in New York City in June 1882. He transferred his commitment to socialism to his new country and devoted all the time he could spare from work to the study and teaching of radical ideas to the Jewish working men of New York. Cahan joined the Socialist Labor Party of America, writing articles on socialism and science, and translating literary works for the pages of its Yiddish language paper, The Arbeiter Zeitung (The Workers’ News). Cahan saw himself as an educator and enlightener of the impoverished Jewish working class of the city, “meeting them on their own ground and in their own language.” Cahan’s contribution to Yiddish-language socialist propaganda was massive, as before his arrival educated Jewish emigres from the old Russian empire tended to speak Russian.

During his years of activity, Cahan was either originator, collaborator or editor of almost all the earlier socialist periodicals published in Yiddish in the United States. From 1903 until 1946, Cahan ran The Jewish Daily Forward (Forverts), a socialist Yiddish-language daily in New York. In 1906 he introduced an advice column named A Bintel Brief.

Cahan quickly mastered the English language and, four years after his arrival in New York, taught immigrants in one of the evening schools. Later, he began to contribute articles to The Sun and other newspapers printed in English and was for several years employed in a literary capacity by The Commercial Advertiser, where we was a regular contributor.

His first novel, Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto, was published in 1896. Cahan’s next work of fiction, The Imported Bridegroom and Other Stories, published in 1898, was also well received and favorably noticed by the general press. Of his shorter publications, an article about the Russian Jews in the United States, which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, July 1898, deserves special mention. His other important work, The Rise of David Levinsky, was published in 1917. Cahan also wrote a five-volume Yiddish-language autobiography, Bleter fun mayn Leben, the first three volumes of which were translated into English as The Education of Abraham Cahan.

Cahan died of congestive heart failure on August 31, 1951.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Cahan

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Henry Hall Caine

Thomas Henry Hall Caine

1853-1931

Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine (May 14, 1853-August 31, 1931), usually known as Hall Caine, was a Manx author. He is best known as a novelist and playwright of the late Victorian and the Edwardian eras. In his time he was exceedingly popular and, at the peak of his success, his novels outsold those of his contemporaries. Many of his novels were also made into films. His novels were primarily romances involving love triangles, but also addressed some of the more serious political and social issues of the day.

Caine acted as secretary to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and at one time he aspired to become a man of letters. To this end he published a number of serious works, but these had little success. He was a lover of the Isle of Man and Manx culture, and purchased a large house, Greeba Castle, on the island. For a time he was a Member of the House of Keys, but he declined to become more deeply involved in politics. A man of striking appearance, he traveled widely and used his travels to provide the settings for some of his novels. He came into contact with, and was influenced by, many of the leading personalities of the day, particularly those of a socialist leaning.

Caine’s novels are considered outdated by creators of English literature curricula today and, despite his immense popularity during his life, he is now virtually unknown and unremembered.

In August 1931, at age 78, Caine slipped into a coma and died. On his death certificate was the diagnosis of “cardiac syncope.”

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hall_Caine

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Erskine Caldwell

Erskine Caldwell

1903-1987

Erskine Preston Caldwell (December 17, 1903-April 11, 1987) was an American author. His writings about poverty, racism and social problems in his native South, like the novels Tobacco Road and God’s Little Acre, won him critical acclaim, but they also made him controversial among fellow Southerners of the time who felt he was deprecating the people of the region.

Caldwell was born in a house in a wooded area outside Moreland, Georgia, the son of a minister of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church. During his early childhood, he was relocated from state to state across the American South, as his father found jobs in various churches.

Later, he attended but did not graduate from Erskine College. He was six feet tall, athletic and played football. His political sympathies were with the working class, and he used his experiences with common workers to write books that extolled the simple life of those less fortunate than he was. Later in life, he gave seminars on low-income tenant-sharecroppers in the American South.

His first and second published works were Bastard (1929) and Poor Fool (1930), but the works for which he is most famous are his novels, Tobacco Road (1932) and God’s Little Acre (1933).

When his first book was published, it was banned and copies were seized by authorities. Later, with the publication of God’s Little Acre, authorities, at the instigation of The New York Literary Society (apparently incensed at Caldwell’s choice of title), arrested Caldwell and seized his copies when he went to New York for a book-signing event. A trial exonerated Caldwell and he counter-sued for false arrest and malicious prosecution.

Through the 1930s, Caldwell and his first wife, Helen, managed a bookstore in Maine. Caldwell was married to photographer Margaret Bourke-White from 1939 to 1942, and they collaborated on three photo-documentaries: You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), North of the Danube (1939) and Say, Is This the USA? (1941).

During World War II, Caldwell obtained papers from the USSR that allowed him to travel to Ukraine and work as a foreign correspondent documenting the war effort there. Disillusionment with the intrigues of the Stalinist regime caused him to compose a four-page short story, “Message for Genevieve,” published on returning to the United States during 1944. After he returned from World War II, Caldwell took up residence in San Francisco.

During the last 20 years of his life, he got into the habit of traveling around the world for six months of each year, and he took with him notebooks in which to jot down his ideas. Many of these notebooks were not published, but can be examined in a museum dedicated to him. The house in which he was born was moved from its original site, preserved and was made into a museum in the town square of Moreland, Ga.

Caldwell, a heavy smoker, died from complications of emphysema and lung cancer on April 11, 1987, in Paradise Valley, Arizona. He is interred in Scenic Hills Memorial Park, Ashland, Oregon.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erskine_Caldwell

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

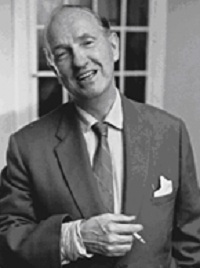

Morley Callaghan

Morley Callaghan

1903-1990

Morley Callaghan was born in Toronto in 1903 to Roman-Catholic parents. He attended St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto, from 1921-25. He earned a general arts degree by taking classes across a multiplicity of disciplines. He also participated in a wide variety of extra-curricular activities and worked part-time for The Toronto Star Weekly, where he met Ernest Hemingway, who became an early mentor. Although he completed a law degree in 1928, Callaghan’s first love was writing.

Callaghan’s first novel, Strange Fugitive, appeared in 1928. In 1929, he signed with a publishing house in New York to produce his first collection of short stories, A Native Argosy. He married and sailed to France, where he socialized with Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and James Joyce in Paris. During a friendly boxing match with Hemingway he knocked out the American novelist and, as a result, their friendship was never the same. Callaghan was heavily influenced by American naturalist literature, apparent in such novels as It’s Never Over (1930) and A Broken Journey (1932). His most commercially popular book came in 1934 with Such Is My Beloved. He followed with They Shall Inherit the Earth (1935), Now That April’s Here and Other Stories (1936) and More Joy in Heaven (1937). These books, with their Christian theological themes, complex characterizations and ambiguous treatment of love, established Callaghan as an important figure in North American literary circles.

The war saw his financial success wane and he began to work once again as a professional writer. He wrote for newspapers and radio in order to support his wife and two sons. He felt that his inspiration was beginning to falter. But after the deaths of three close family members, Callaghan once again turned to the redemptive power of literature. In the 1950s and 1960s, he involved himself in many aspects of writing, including working with the Writer’s Union. In 1951, he finally won a Governor-General’s Award for The Loved and the Lost. He also wrote That Summer in Paris (1963), a memoir of his summer in Paris in 1929.

During the last two decades of his life, Callaghan wrote with self-reflexive irony. He would often portray himself in his later works in a playful way and would refer to his early works and reviews. He was awarded a number of honors later in his life, including the Lorne Pierce Medal (1960) and the Order of Canada (1982). He died in Toronto in 1990. One of his sons, Barry Callaghan, is a successful writer and editor.

Source: http://www.athabascau.ca/writers/mcallaghan.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Charles Stuart Calverley

Charles Stuart Calverley

1831-1884

Charles Stuart Calverley (December 22, 1831-February 17, 1884) was an English poet and wit. He was the literary father of what has been called “the university school of humor.”

He was born at Martley, Worcestershire, and given the name Charles Stuart Blayds. In 1852, his father, the Rev. Henry Blayds, resumed the old family name of Calverley, which his grandfather had exchanged for Blayds in 1807. Charles went up to Balliol College, Oxford, from Harrow School in 1850, and was soon known in Oxford as the most daring and high-spirited undergraduate of his time. He was a universal favorite, a delightful companion, a brilliant scholar and the playful enemy of all “dons.” In 1851, he won the Chancellor’s prize for Latin verse, but it is said that the entire exercise was written in an afternoon, when his friends had locked him into his rooms, refusing to let him out until he had finished what they were confident would prove the prize poem.

A year later, to avoid the consequences of a college escapade (he had been expelled from Oxford), he too changed his name to Calverley and moved to Christ’s College, Cambridge. Here he was again successful in Latin verse, the only undergraduate to have won the Chancellor’s prize at both universities. In 1856, he took second place in the first class in the Classical Tripos.

He was elected fellow of Christ’s (1858), published Verses and Translations in 1862 and was called to the bar in 1865. Injuries sustained in a skating accident prevented him from following a professional career and, during the last years of his life, he was an invalid. He died of Bright’s disease.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Stuart_Calverley

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Italo Calvino

Italo Calvino

1923-1985

Italo Calvino (October 15, 1923-September 19, 1985) was an Italian writer and novelist. Born in Santiago de Las Vegas, Cuba, to botanists Mario Calvino and Evelina Mameli, he soon moved to Italy, where his family originated and where he lived most of his life. He stayed in San Remo, in the Riviera, for some 20 years.

In 1947, Calvino graduated from Turin’s university with a thesis on Joseph Conrad and started working with the official Communist paper, L’Unita; he also had a short relationship with the Einaudi publishing house, which put him in contact with Norberto Bobbio, Natalia Ginzburg, Cesare Pavese and Elio Vittorini. With Vittorini he wrote for the weekly Il Politecnico (a cultural magazine of the university). He then left Einaudi to work mainly with L’Unita and the newborn communist weekly political magazine, Rinascita. In 1950, he worked again for the Einaudi house, where he became responsible for the literary volumes. The following year, presumably in order to verify a possibility of advancement in the communist party, he visited the Soviet Union. The reports and correspondence he produced from this visit where later collected and earned him literary prizes.

In 1952, Calvino wrote with Giorgio Bassani for Botteghe Oscure, a magazine named after the popular name of the party’s head offices, and worked for Il Contemporaneo, a Marxist weekly. It was in 1957 that Calvino unexpectedly left the Communist party; his letter of resignation (soon famous) was published in L’Unita. He found new spaces for his periodic writings in the magazines Passato e Presente and Italia Domani. Together with Vittorini, he became a co-editor of Il Menabo di letteratura, a position that he held for many years.

Despite the previously severe restrictions for foreigners holding communist views, he was allowed to visit the United States, where he stayed for six months (four of which in New York), after an invitation by the Ford Foundation. Back in Italy, and once again working for Einaudi, he started publishing some of his cosmicomics in Il Caffe, a literarian magazine.

In 1975, he was made Honorary Member of the American Academy; the following year he was awarded the Austrian State Prize for European Literature. He visited Japan and Mexico and gave lectures in several American towns. In 1981, he was awarded the prestigious French Legion d’Honneur.

In 1985, he died in Siena of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Source: http://www.biographybase.com/biography/Calvino_Italo.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Campbell

Thomas Campbell

1777-1844

Thomas Campbell (July 27, 1777-June 15, 1844) was a Scottish poet chiefly remembered for his sentimental poetry dealing specially with human affairs. He was also one of the initiators of a plan to found what became the University of London. In 1799, he wrote “The Pleasures of Hope,” a traditional 18th century survey in heroic couplets. He also produced several stirring patriotic war songs: “Ye Mariners of England,” “The Soldier’s Dream,” “Hohenlinden” and, in 1801, “The Battle of Baltic.”

Born in Glasgow, Campbell was the youngest son of Alexander Campbell, of the Campbells of Kirnan, Argyll. His father belonged to a Glasgow firm trading in Virginia and lost his money in consequence of the American Revolutionary War. Campbell, who was educated at the Glasgow High School and University of Glasgow, won prizes for classics and for verse-writing. He spent the holidays as a tutor in the western Highlands. His poem, “Glenara,” and the “Ballad of Lord Ullin’s Daughter” owe their origin to a visit to Mull. In May 1797, he went to Edinburgh to attend lectures on law. He supported himself by private teaching and by writing. These early days in Edinburgh influenced such works as “The Wounded Hussar,” “The Dirge of Wallace” and the “Epistle to Three Ladies.”

In 1799, “The Pleasures of Hope” was published. During a tour of Germany, he wrote some of his best lyrics: “Hohenlinden,” “Ye Mariners of England” and “The Soldier’s Dream.” In 1809, he published a narrative poem in the Spenserian stanza, “Gertrude of Wyoming,” with which were printed some of his best lyrics.

In 1812, he delivered a series of lectures on poetry in London at the Royal Institution and was urged by Sir Walter Scott to become a candidate for the chair of literature at Edinburgh University. His pecuniary anxieties were relieved in 1815 by a legacy of £4000. He continued to occupy himself with his Specimens of the British Poets, the design of which had been projected years before. The work was published in 1819. In 1820, he accepted the editorship of The New Monthly Magazine and, in the same year, made another tour in Germany.

Four years later appeared his “Theodric,” a not very successful poem of domestic life. He was elected Lord Rector of Glasgow University (1826-1829) in competition against Sir Walter Scott. In 1834, he traveled to Paris and Algiers, where he wrote his “Letters from the South” (printed 1837). Campbell’s other works include a Life of Mrs. Siddons (1842) and a narrative poem, “The Pilgrim of Glencoe” (1842).

He died at Boulogne in 1844 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Campbell_%28poet%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Campion

Thomas Campion

1567-1620

Born in London on February 12, 1567, to John and Lucy Campion, Thomas Campion was a physician, a composer and a poet. His parents died while he was a child and, at the age of 14, he and a step-brother were sent away to Cambridge. Campion did not earn a degree at Cambridge, but he came into contact with writers such as Thomas Nashe and Gabriel Harvey. In 1586, he enrolled at Gray’s Inn, a law school, where he performed in plays and masques. The facts of his life from this time until 1602 remain vague; in 1602, Campion entered the University of Caen and, shortly thereafter, at the age of 40, took up a medical practice in London.

His first published works were five songs, which appeared in 1591. Campion’s first collection of poems, Thomae Campiani Poemata, was published in Latin in 1595. The book included more than 129 epigrams as well as a number of elegies and an incomplete epic poem. The epigrams show Campion’s ability to draw a portrait in a few precise lines; he would later publish 453 epigrams in Epigrammatum Libri II (1619).

By 1597, Campion had focused his attention almost completely on writing the words and music for songs. In 1601, he contributed 21 songs and a brief treatise on song to the Philip Rosseter’s Book of Ayeres. Rosseter was King James I’s lutenist. Campion would publish four more books of ayeres, or solo songs, including “Light Conceits of Lovers” (1613) and The Third and Fourth Booke of Ayres (circa 1617).

Campion’s book of prosody, Observations in the Art of English Posie, was published in 1602. In it, he explored the relationship of music and poetry, and warned against “the childish titillation of rhyming.” Campion also wrote a number of libretti for masques performed in King James’ court, including Lord Hay’s Masque (1607) and The Squire’s Masque (1614). These works, commissioned by King James, allowed Campion to associate with many of England’s artistic and aristocratic elite.

Campion died on March 1, 1620, in London, probably of the plague, and was buried at St. Dunstan’s-in-the-West, Fleet Street.

Source: http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/293

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Albert Camus

Albert Camus

1913-1960

Albert Camus was born on November 7, 1913, in Mondovi, Algeria, then part of France.

His schooling was completed only with help from scholarships. At the University of Algiers, he was a brilliant student of philosophy, focusing on the comparison of Hellenism and Christianity. Camus is described as both a physical and mental athlete. While still a student, he founded a theater and both directed and acted in plays. At 17 he contracted tuberculosis, which kept him from further sports, the military and teaching jobs.

Camus worked at various jobs before becoming a journalist in 1938. His first published works were L’Envers et l’endroit (1937; The Wrong Side and the Right Side) and Noces (1938; Festivities), books of essays dealing with the meaning of life and its joys, as well as its underlying meaninglessness. His first novel, L’Etranger (The Stranger), published in 1942, focuses on the negative aspect of man.

Unable to find work in France during World War II because Germany invaded and occupied France, Camus returned to Algeria in 1941 and finished his next book, Le Mythe de Sisyphe (The Myth of Sisyphus), also published in 1942. Back in France that year, Camus joined a Resistance group and engaged in underground journalism until the Liberation in 1944, when he became editor of the former Resistance newspaper, Combat, for three years. Also during this period his first two plays were staged: Le Malentendu (Cross-Purpose) in 1944 and Caligula in 1945. In 1947, Camus published his second novel, La Peste (The Plague). Camus’ next important book was L’Homme revolte (1951; The Rebel).

In 1957, Camus received the great honor of the Nobel Prize in Literature for his works. In the same year he began to work on a fourth important novel and was also about to become the director of a major Paris theater when, on January 4, 1960, he was killed in a car crash near Paris. He was 46 years old.

Source: http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ca-Ch/Camus-Albert.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Truman Capote

Truman Capote

1924-1984

Truman Streckfus Persons was born on September 24, 1924, in New Orleans, Louisiana. His parents, Archulus Persons and Lillie Mae Faulk, were divorced when he was four years old. He lived with relatives in Monroeville, Alabama, while his mother and her second husband, Cuban businessman Joseph Capote, lived in New York.

His closest friends at this time were an elderly cousin, Miss Sook Faulk, and a neighboring tomboy, Harper Lee (1926-). She later became an award-winning author herself, writing To Kill a Mockingbird. Both friends appear as characters in Capote’s early fiction.

When he was nine years old, his mother brought her son to live in Manhattan, New York. He then took on his adopted last name, Capote. He continued to spend summers in the South. He did poorly in school, even though psychological tests proved that his Intelligence Quotient (IQ) was above genius level. Capote developed an outgoing personality to hide his loneliness and unhappiness.

Capote began secretly writing at an early age. When he completed high school, he worked for The New Yorker. There he wrote articles and short stories. When he was 17, several magazines published his short stories. That exposure eventually led to a contract to write his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms.

Many of Capote’s early stories were written when he was in his teens and early 20s. Collected in A Tree of Night and Other Stories, these stories show the influence of Gothic writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and William Faulkner.

In some of Capote’s works of the 1950s, his attention is turned away from traditional fiction. In Local Color, he wrote a collection of pieces retelling his impressions and experiences while in Europe. In The Muses Are Heard: An Account, he wrote essays about his travels in Russia with a touring theater company that presented the play, Porgy and Bess.

Before Capote found his main subject, he published one more traditional novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It was an engaging story of Manhattan playgirl Holly Golightly. From these projects, Capote developed the idea of creating work that would combine fact and fiction. The result was In Cold Blood.

In the late 1960s Capote began suffering from writer’s block. He spent most of his time revising or throwing out his works in progress. During the mid-1970s he published several chapters of Answered Prayers in Esquire magazine.

In 1983, Music for Chameleons, a final collection of short prose pieces, was published. Afterward, Capote took to alcohol, drug addiction and suffered poor health. He died in Los Angeles, California, on August 24, 1984, shortly before his 60th birthday.

Source: http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ca-Ch/Capote-Truman.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Orson Scott Card

Orson Scott Card

1951-

Orson Scott Card (born August 24, 1951) is an American author, critic, public speaker, essayist, columnist and political activist. He writes in several genres but is primarily known for his science fiction. His novel, Ender’s Game (1985), and its sequel, Speaker for the Dead (1986), both won Hugo and Nebula Awards, making Card the only author to win both of science fiction’s top U.S. prizes in consecutive years.

Card is the son of Willard and Peggy Card, third of six children and the older brother of composer and arranger Arlen Card. He was born in Richland, Washington, and grew up in Santa Clara, California, as well as Mesa, Arizona, and Orem, Utah. He served as a missionary for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Brazil and graduated from Brigham Young University and the University of Utah; he also spent a year in a Ph.D. program at the University of Notre Dame.

Card lives in Greensboro, North Carolina, an environment that played a significant role in Ender’s Game and many of his other works.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orson_Scott_Card

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Richard Carew

Richard Carew

1555-1620

Richard Carew, English poet and antiquary, was born on July 17, 1555, at Antony House, East Antony, Cornwall. At the age of 11, he entered Christ Church, Oxford, and when only 14 was chosen to carry on an extempore debate with Sir Philip Sidney, in presence of the earls of Leicester and Warwick and other noblemen. From Oxford he removed to the Middle Temple, where he spent three years, and then went abroad. By his marriage with Juliana Arundel in 1577 he added Coswarth to the estates he had already inherited from his father.

In 1586, he was appointed high-sheriff of Cornwall. He entered parliament in 1584 and served under Sir Walter Raleigh, then lord lieutenant of Cornwall, as treasurer. He became a member of the Society of Antiquaries in 1589 and was a friend of William Camden and Sir Henry Spelman.

His great work is The Survey of Cornwall, published in 1602, and reprinted in 1769 and 1811. It still possesses interest, apart from its antiquarian value, for the picture it gives of the life and interests of a country gentleman in the days of Elizabeth I.

Carew’s other works are: a translation of the first five Cantos of Tasso’s Gerusalemme (1594), printed in the first instance without the author’s knowledge, and entitled Godfrey of Balloigne, or the Recouerie of Hierusalam; The Examination of Men’s Wits (1594), a translation of an Italian version of John Huarte’s Examen de Ingenios; and An Epistle Concerning the Excellences of the English Tongue (1605).

Carew died on November 6, 1620.

Source: http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Richard_Carew

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Carew

Thomas Carew

1594-1640

Thomas Carew (pronounced Carey) was born, possibly at West Wickham, Kent, in either 1594 or 1595. His father, lawyer Matthew Carew, moved the family to London about 1598. Nothing is known of Carew’s education before he matriculated at Merton College, Oxford, in 1608. Graduating B.A. in 1610/11, he was incorporated B.A. of Cambridge in 1612, after which he was admitted to the Middle Temple. From 1613 to 1616 Carew served as secretary to Sir Dudley Carleton on embassies to Italy and the Netherlands. After being fired for making insulting remarks about Carleton and his wife, Carew returned to England in a futile search for employment. In 1619, his father having died the previous year, Carew joined an embassy to Paris headed by Sir Edward Herbert (later Lord Herbert of Chirbury). Possibly, he met there the Italian poet Giambattista Marino.

In 1622, Carew’s first poem was published: “Verses prefixed to Thomas May’s comedy, The Heir.” In the early 1620s Carew associated with Ben Jonson and his circle and also frequented the court. In 1630, Carew was made a gentleman of Charles I’s Privy Chamber Extraordinary. He was named Sewer in Ordinary to the King (that is, an official in charge of the royal dining arrangements). It is said he was “high in favour with that king, who had a high opinion of his wit and abilities.”

This reputation did nothing to damage his career as a poet, soldier and courtier. His society verses, such as “A Divine Mistress” and “Disdain Returned,” were prized for their wit. Carew’s masque, Coelum Britannicum, performed before the king in 1634, though full of jokes and allusions, draws upon an important work by the 16th century Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno. Much of Carew’s poetry was sexually explicit far beyond the norms of his age, and he was a reputed libertine. Yet he translated nine of the Psalms and wrote one of the finest elegies of the period: “An Elegy on the Death of the Dean of St. Paul’s, Dr. John Donne.”

Perhaps the most interesting of Carew’s achievements is his verse criticism of his contemporaries. Formal criticism was in its infancy during the early 17th century. Carew’s commendatory, complimentary and elegiac poems provide some of the best evidence concerning the literary values of the age.

Carew died on March 23, 1640, and was buried in St. Dunstan’s-in-the-West, Westminster. His Poems were published the same year, to be followed by the second edition “revised and enlarged” in 1642.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/carew/carewbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle

1795-1881

Thomas Carlyle (December 4, 1795-February 5, 1881) was a Scottish satirical writer, essayist, historian and teacher during the Victorian era. He called economics “the dismal science,” wrote articles for the Edinburgh Encyclopedia and became a controversial social commentator.

Coming from a strict Calvinist family, Carlyle was expected by his parents to become a preacher but, while at the University of Edinburgh, he lost his Christian faith. Calvinist values, however, remained with him throughout his life. This combination of a religious temperament with loss of faith in traditional Christianity made Carlyle’s work appealing to many Victorians who were grappling with scientific and political changes that threatened the traditional social order.

Carlyle was born in Ecclefechan, Dumfries and Galloway. His parents determinedly afforded him an education at Annan Academy, Annan, where he was bullied and tormented so much that he left after three years. After attending the University of Edinburgh, Carlyle became a mathematics teacher, first in Annan and then in Kirkcaldy.

In 1819-1821, Carlyle returned to the University of Edinburgh, where he suffered an intense crisis of faith and conversion that would provide the material for Sartor Resartus (The Tailor Retailored), which first brought him to the public’s notice. He began reading deeply in German literature. Carlyle’s thinking was heavily influenced by German Idealism, in particular the work of Johann Gottlieb Fichte. He established himself as an expert on German literature in a series of essays for Fraser’s Magazine and by translating German writers, notably Goethe (the novel, Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre). He also wrote Life of Schiller (1825).

His residence for much of his early life, after 1828, was a farm in Craigenputtock and a house in Dumfrieshire, Scotland, where he wrote many of his works, including some of his most distinguished essays, and he began a lifelong friendship with the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1834, Carlyle moved to the Chelsea section of London, where he was then known as the “sage of Chelsea” and became a member of a literary circle that included the essayists Leigh Hunt and John Stuart Mill. In London, Carlyle wrote The French Revolution, A History (1837), as a historical study concerning oppression of the poor, which was immediately successful.

His last major work was the epic Life of Frederick the Great (1858-65). Later writings were generally short essays, often indicating the hardening of Carlyle’s political positions. In 1866, Thomas Carlyle partly retired from active society. He was appointed rector of the University of Edinburgh.

Carlyle died on February 5, 1881 in London.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Carlyle

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lewis Carroll

Lewis Carroll

1832-1898

Lewis Carroll was born Charles Lutwidge Dodgson on January 27, 1832, the eldest son and third of 11 children born to Frances Jane Lutwidge and the Reverend Charles Dodgson. Carroll had a happy childhood. His mother was patient and gentle; his father, despite his religious duties, tutored all of his children and raised them to be good people. Carroll frequently made up games and wrote stories and poems, some of which were similar to his later published works, for his seven sisters and three brothers.

Although his years at Rugby School (1846-49) were unhappy, he was recognized as a good student and in 1850 he was admitted to further study at Christ Church, Oxford, England. He graduated in 1854; in 1855, he became mathematical lecturer at the college. This permanent appointment, which not only recognized his academic skills but also paid him a decent sum, required Carroll to take holy orders in the Anglican Church and to remain unmarried. He agreed to these requirements and was made a deacon in 1861.

Among adults, Carroll was reserved but he did not avoid their company as some reports have stated. He attended the theater frequently and was absorbed by photography and writing. In the mid-1850s Carroll also began writing both humorous and mathematical works. In 1856, he created the pseudonym “Lewis Carroll” by translating his first and middle names into Latin, reversing their order, then translating them back into English. His mathematical writing, however, appeared under his real name.

In 1856, Carroll met Alice Liddell, the four-year-old daughter of the head of Christ Church. During the next few years, Carroll often made up stories for Alice and her sisters. In July 1862, while on a picnic with the Liddell girls, Carroll recounted the adventures of a little girl who fell into a rabbit hole. Alice asked him to write the story out for her. He did so, calling it Alice’s Adventures under Ground. After some changes, this work was published in 1865 as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Encouraged by the book’s success, Carroll wrote a second volume, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1872). Based on the chess games Carroll played with the Liddell children, it included material he had written before he knew them. The first section of Jabberwocky, for example, was written in 1855. More of Carroll’s famous Wonderland characters – such as Humpty Dumpty, the White Knight, and Tweedledum and Tweedledee – appear in this work than in Alice in Wonderland.

Carroll published several other nonsense works, including The Hunting of the Snark (1876), Sylvie and Bruno (1889) and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893). He also wrote a number of pamphlets poking fun at university affairs, which appeared under a fake name or without any name at all, and he composed several works on mathematics under his true name. In 1881, Carroll gave up his lecturing to devote all of his time to writing. From 1882 to 1892, however, he was curator of the common room at Christ Church.

After a short illness, he died on January 14, 1898.

Source: http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ca-Ch/Carroll-Lewis.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Hayden Carruth

Hayden Carruth

1921-2008

Hayden Carruth was born on August 3, 1921, in Waterbury, Connecticut, and educated at both the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Chicago, where he earned a master’s degree.

His first collection of poems, The Crow and the Heart, was published in 1959. Since then, he published more than 30 books, including Toward the Distant Islands: New and Selected Poems (2006) and Doctor Jazz: Poems 1996-2000 (2001).

Other poetry titles include Scrambled Eggs & Whiskey: Poems, 1991-1995 (1996), which received the National Book Award for Poetry; Collected Longer Poems (1994); Collected Shorter Poems, 1946-1991 (1992), which received the National Book Critics’ Circle Award; The Sleeping Beauty (1990); and Tell Me Again How the White Heron Rises and Flies across Nacreous River at Twilight Toward the Distant Islands (1989).

Known also for his criticism, Carruth is the author of several prose collections, including Selected Essays & Reviews (1996) and Sitting In: Selected Writings on Jazz, Blues and Related Topics (1993), as well as nonfiction works, including Beside the Shadblow Tree: A Memoir of James Laughlin (1999) and Reluctantly: Autobiographical Essays (1998).

He is also the author of a novel, Appendix A (1963), and has edited a number of anthologies, including The Voice That Is Great Within Us: American Poetry of the Twentieth Century (1970).

Informed by his political radicalism and sense of cultural responsibility, many of Carruth’s best-known poems are about the people and places of northern Vermont, as well as rural poverty and hardship.

Carruth received fellowships from the Bollingen Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, and a 1995 Lannan Literary Fellowship. He was presented with the Lenore Marshall Award, the Paterson Poetry Prize, the Vermont Governor’s Medal, the Carl Sandburg Award, the Whiting Award and the Ruth Lilly Prize, among many others.

He taught at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, and at the Graduate Creative Writing Program at Syracuse University.

Carruth lived in Vermont for many years before residing in Munnsville, New York, with his wife, the poet Joe-Anne McLaughlin Carruth. He died September 29, 2008.

Source: http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/232

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Angela Carter

Angela Carter

1940-1992

Angela Carter (May 7, 1940-February 16, 1992) was an English novelist and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism and picaresque works.

Born Angela Olive Stalker in Eastbourne, in 1940, Carter was evacuated as a child to live in Yorkshire with her maternal grandmother. She began work as a journalist on the Croydon Advertiser, following in the footsteps of her father. Carter attended the University of Bristol, where she studied English literature.

She married twice, first in 1960 to Paul Carter. They separated in 1970. In 1969 Carter used the proceeds of her Somerset Maugham Award to leave her husband and relocate for two years to Tokyo, Japan, where she claims in Nothing Sacred (1982) that she “learnt what it is to be a woman and became radicalized.” She wrote about her experiences there in articles for New Society and a collection of short stories, Fireworks: Nine Profane Pieces (1974), and evidence of her experiences in Japan can also be seen in The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972). She then explored the United States, Asia and Europe, helped by her fluency in French and German. She spent much of the late 1970s and 1980s as a writer in residence at universities, including the University of Sheffield, Brown University, the University of Adelaide and the University of East Anglia. In 1977, Carter married Mark Pearce, with whom she had one son.

As well as being a prolific writer of fiction, Carter contributed many articles to The Guardian, The Independent and New Statesman, collected in Shaking a Leg. Her screenplays are published in the collected dramatic writings, The Curious Room, together with her radio scripts, a libretto for an opera of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, an unproduced screenplay entitled The Christchurch Murders (based on the same true story as Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures) and other works. Her novel, Nights at the Circus, won the 1984 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for literature.

Angela Carter died aged 51 in 1992 at her home in London after developing lung cancer.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angela_Carter

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Raymond Carver

Raymond Carver

1938-1988

Raymond Clevie Carver Jr. (May 25, 1938-August 2, 1988) was an American short story writer and poet. Carver is considered a major American writer of the late 20th century and also a major force in the revitalization of the short story in the 1980s.

Carver was born in Clatskanie, Oregon, a mill town on the Columbia River, and grew up in Yakima, Washington. His father, a skilled sawmill worker from Arkansas, was a fisherman and a heavy drinker. Carver’s mother worked on and off as a waitress and a retail clerk. His one brother, James Franklin Carver, was born in 1943.

Carver was educated at local schools in Yakima, Washington. In June 1957, aged 19, he married 16-year-old Maryann Burk, who had just graduated from a private Episcopal school for girls. Their daughter, Christine La Rae, was born in December 1957. When their second child, a boy named Vance Lindsay, was born the next year, Carver was 20. Carver supported his family by working as a janitor, sawmill laborer, delivery man and library assistant. During their marriage, Maryann worked as a waitress, salesperson, administrative assistant and high school English teacher.

Carver became interested in writing in California, where he had moved with his family because his mother-in-law had a home in Paradise. Carver attended a creative-writing course taught by the novelist John Gardner, who became a mentor and had a major influence on Carver’s life and career. Carver continued his studies first at Chico State University and then at Humboldt State College in Arcata, California, where he studied with Richard Cortez Day and received his B.A. in 1963. During this period, he was first published and served as editor for Toyon, the university literary magazine, in which he included several of his own pieces under pseudonyms. He later attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, at the University of Iowa, for one year. Maryann graduated from San Jose State College in 1970 and taught English at Los Altos High School until 1977.

His first published story, “The Furious Seasons,” appeared in 1960. His first collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?, was first published in 1976; the title story appeared in the Best American Short Stories 1976 collection.

In the mid-1960s Carver and his family lived in Sacramento, where he worked as a night custodian at Mercy Hospital. In 1967 he moved his family to Palo Alto, California, so that he could take a job as a textbook editor for Science Research Associates. He worked there until he was fired in 1970 for his inappropriate writing style. In the 1970s and 1980s, as his writing career began to take off, Carver taught for several years at universities throughout the United States.

During his years of working different jobs, rearing children and trying to write, Carver started to drink heavily. By his own admission, eventually he more or less gave up writing and took to full-time drinking. After being hospitalized three times (between June 1976 and February or March 1977), Carver began his “second life” and stopped drinking on June 2, 1977, with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Carver was nominated again in 1984 for his third major press collection, Cathedral, the volume generally perceived as his best. Included in the collection are the award-winning stories, “A Small, Good Thing” and “Where I’m Calling From.”

On August 2, 1988, Carver died in Port Angeles, Washington, from lung cancer at the age of 50. In the same year, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Carver

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Alice and Phoebe Cary

Alice and Phoebe Cary

1820-1871/1824-1871

Born near Cincinnati, Ohio, Alice on April 26, 1820, and Phoebe on September 4, 1824, the Cary sisters grew up on a farm and received little schooling. Nevertheless, they were for their time well educated, Alice by their mother and Phoebe by Alice, and they early developed a taste for literature.

Alice’s first published poem appeared in The Sentinel, a Cincinnati Universalist newspaper, when she was 18; for 10 years thereafter she continued to contribute poems and prose sketches to various periodicals with no remuneration. Phoebe began to write under Alice’s guidance and had her first poem published in a Boston newspaper about the time of Alice’s first. Their work attracted the favorable notice of Edgar Allan Poe, Horace Greeley, John Greenleaf Whittier and Rufus W. Griswold, through whose recommendation their joint works were issued as Poems of Alice and Phoebe Carey [sic] (1850). Some two-thirds of the poetry was the work of Alice. Their book’s modest success encouraged the sisters to move to New York City.

In New York City, Alice and Phoebe became regular contributors to Harper’s, The Atlantic Monthly and other periodicals. Alice, much more prolific than her sister, enjoyed the higher reputation during her lifetime, although Phoebe was later held in greater critical esteem for the wit and feeling of her poems. Their salon became a popular meeting place for the leading literary lights of New York, and both women were famed for their hospitality.

Among Alice’s books were two volumes of reminiscent sketches entitled Clovernook Papers (1852, 1853), three novels and several volumes of poetry. Phoebe devoted much of her time to keeping house and, in later years, to caring for Alice. As a result, she published only Poems and Parodies (1854) and Poems of Faith, Hope and Love (1868), but one of her religious verses, “Nearer Home” (sometimes called, from the first line, “One Sweetly Solemn Thought”), became widely popular as a hymn.

Both sisters supported the women’s rights movement. Phoebe was for a short time an assistant editor of Susan B. Anthony’s paper, The Revolution. In 1868, Alice reluctantly agreed to serve as first president of Sorosis, the pioneer women’s club founded by Jane Croly. After a long illness, Alice died in New York City on February 12, 1871; exhausted by grief and stricken with malaria, Phoebe died on July 31, 1871, in Newport, Rhode Island.

Source: http://www.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap3/cary.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Elizabeth Cary

Elizabeth Cary

1585-1639

Elizabeth Cary, Lady Falkland, nee Tanfield, was an English poet, translator and dramatist. Precocious and studious, she was known from a young age for her learning and knowledge of languages.

At the age of 17, she married Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland, and over the next decades she bore 11 children, including Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland and Patrick Cary. She was disinherited by her father for using part of her jointure to meet expenses, and the family were in financial difficulties from thereon. Her husband abandoned her to poverty in 1626 and denied her access to their children when she made public her conversion to Catholicism. Despite several orders of the Privy Council, he refused her a maintenance in an apparent effort to force her to recant. She lived in abject circumstances, though she still managed to maintain connections with a constellation of politically prominent women. Her husband died in 1633 and she sought to regain custody of her children. She was questioned in the Star Chamber for kidnapping her sons (she had previously, and more easily, gained custody of her daughters), but although she was threatened with imprisonment there is no record of any punishment.

She is best known now for The Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry (1613), the first original play in English known to have been written by a woman. She was also the first English woman author to be the subject of a literary biography – The Lady Falkland: Her Life was written by one of her daughters, probably in the 1643-50 era, though not published till 1861.

Cary died in London in 1639.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Cary,_Lady_Falkland

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Willa Cather

Willa Cather

1873-1947

Willa Sibert Cather (December 7, 1873-April 24, 1947) was an American author who achieved recognition for her novels of frontier life on the Great Plains, in works such as O Pioneers!, My Antonia and The Song of the Lark. In 1923, she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for One of Ours (1922), a novel set during World War I.

Cather was born on her maternal grandmother’s farm in the Back Creek Valley near Winchester, Virginia. Her father was Charles Fectigue Cather (d. 1928), whose family had lived on land in the valley for six generations. Her mother was Mary Virginia Boak (d. 1931), a former school teacher. Within a year of Cather’s birth, the family moved to Willow Shade, a Greek Revival-style home on 130 acres given to them by her paternal grandparents.

The Cathers moved to Nebraska in 1883, joining Charles’ parents, when Willa was nine years old. Her father tried his hand at farming for 18 months, then he moved the family into the town of Red Cloud, where he opened a real estate and insurance business and the children attended school for the first time. Cather’s time in the western state, still on the frontier, was a deeply formative experience for her. She was intensely moved by the dramatic environment and weather, and the various cultures of the European-American, immigrant and Native American families in the area. Her town was named for the renowned Oglala Lakota chief.

Cather had planned to major in science at the University of Nebraska – she hoped to become a medical doctor. After her essay about Thomas Carlyle was published in The Nebraska State Journal during her freshman year, she became a regular contributor to The Journal, changed her major and graduated in 1894 with a B.A. in English.

In 1896, Cather moved to Pittsburgh after being hired to write for The Home Monthly, a women’s magazine patterned after the successful Ladies Home Journal. A year later, she became a telegraph editor and drama critic for The Pittsburgh Leader and frequently contributed poetry and short fiction to The Library, another local publication. In Pittsburgh, she taught Latin, algebra and English composition at Central High School for one year. She next taught English and Latin at Allegheny High School, where she became the head of the English department.

In 1906, Cather moved to New York City upon receiving a job offer on the editorial staff from McClure’s Magazine. During her first year at McClure’s, she wrote a critical biography of Christian Science founder, Mary Baker Eddy. Mary Baker Eddy: The Story of Her Life and the History of Christian Science was published in McClure’s in 14 installments over the next 18 months and later in book form.

McClure’s serialized Cather’s first novel, Alexander’s Bridge (1912). Cather followed Alexander’s Bridge with her Prairie Trilogy: O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915) and My Antonia (1918). Through the 1910s and 1920s, Cather was firmly established as a major American writer, receiving the Pulitzer Prize in 1922 for her novel, One of Ours.

Cather died on April 24, 1947 in New York City of a cerebral hemorrhage and was buried in the Old Burying Ground in Jaffrey, New Hampshire.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willa_Cather

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Gaius Valerius Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus

84-54 BC

Gaius Valerius Catullus (ca. 84 BC-ca. 54 BC) was a Latin poet of the Republican period. His surviving works are still read widely and continue to influence poetry and other forms of art.

Catullus came from a leading equestrian family of Verona in Cisalpine Gaul and, according to St. Jerome, he was born in the town. The family was prominent enough for his father to entertain Caesar, then proconsul of both Gallic provinces. In one of his poems, Catullus describes his happy return to the family villa at Sirmio on Lake Garda near Verona. The poet also owned a villa near the fashionable resort of Tibur (modern Tivoli).

The poet appears to have spent most of his young adult years in Rome. A number of prominent contemporaries appear in his poetry, including Cicero, Caesar and Pompey.

He spent the provincial command year summer 57 to summer 56 BC in Bithynia on the staff of the commander, Gaius Memmius. While in the East, he traveled to the Troad to perform rites at his brother’s tomb, an event recorded in a moving poem.

There survives no ancient biography of Catullus: His life has to be pieced together from scattered references to him in other ancient authors and from his poems. Thus, it is uncertain when he was born and when he died. St. Jerome says that he died in his 30th year, and was born in 87 BC. But the poems include references to events of 55 and 54 BC. Since the Roman consular fasti make it somewhat easy to confuse 87-57 BC with 84-54 BC, many scholars accept the dates 84 BC-54 BC, supposing that his latest poems and the publication of his Libellus coincided with the year of his death.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catullus

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Margaret Cavendish (Duchess of Newcastle)

Margaret Cavendish (Duchess of Newcastle)

1623-1673

In 1623 in Colchester, Essex, Sir Thomas Lucas and his wife Elizabeth had their eighth child, a daughter they named Margaret. The Lucas children were indulged, but they were also encouraged to lead kind and virtuous lives. All were taught by an elderly gentlewoman, who imparted only the rudiments of reading and writing. Margaret and her sisters also learned needlework, singing, dancing and were taught to play the lute and virginal (an early form of the spinet). Her first efforts at writing were what she called her baby books. She wrote 16 of these books, the shortest of which was two or three quires of paper (50-75 pages). The more she wrote, the stronger became her ambition to excel in literature.

The members of Margaret’s family were devoted Royalists. In 1640, when she was 17, the civil war broke out in England. Margaret Lucas fled to Oxford with her sisters and their husbands, where Charles I and his court were in exile, and Margaret became a maid-of-honour to Queen Henrietta Maria. But after the royalist forces were defeated at Marston Moor in 1644, the Queen and her court fled further into exile in France. This flight was traumatic for Margaret as it was her first total separation from her family.

In France, Margaret met William Cavendish, the first Duke of Newcastle, and the couple married in 1645. They lived in comparative poverty during the Interregnum, first in Paris then Antwerp. During this time, Margaret received informal lessons in science and philosophy from both her husband and his brother, Sir Charles Cavendish.

Cavendish returned to England for a time in November of 1651. During that year she spent her days and nights writing her first book, a collection of poems entitled Poems and Fancies. The book caused a sensation, provoking both applause and derision.

Cavendish was a woman of firsts and especially displayed brilliance and freedom of thought in works of science fiction like The Blazing World. Her enthusiasm for science was reflected in books and poems in which she focuses on ideas such as the smallness of an atom and imagines how there might be “other worlds within this world … [a] world in an ear-ring worn by some lady quite unconscious of her responsibility.”

She was the first woman in England who wrote mainly for publication. She published 22 works during her lifetime.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, died suddenly on December 15, 1673 at the age of 50.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/cavendish/cavendishbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

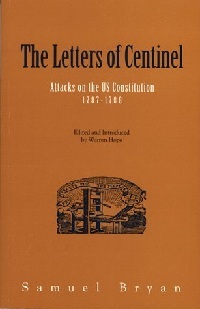

Centinel

Centinel

1787-1788

“Centinel” was an alias used to write a series of 18 articles that were printed in The Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer and The Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal between October 5, 1787, and April 9, 1788.

It is generally accepted by historians that the majority of these articles were written by Samuel Bryan. However, some may have been written by Eleazer Oswald of The Independent Gazetteer.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letters_of_Centinel

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

1547-1616

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was born in Alcala de Henares in the old kingdom of Toledo, Spain. His birth date is unknown but a record states that he was christened on October 9, 1547.

Nothing is known of Cervantes’ life until 1569. In that year, Juan Lopez de Hoyos, a humanist teacher who was devoted to literary culture and whose ideas emphasized nonreligious concerns, brought out a volume in memory of the death of Queen Isabel de Valois in 1568. Cervantes contributed three poems to this work and Lopez de Hoyos wrote of him as “our dear and beloved pupil.” Since Lopez de Hoyos was an admirer of the Dutch humanist Erasmus, Cervantes’ attitudes about religion and his admiration toward Erasmus is reflected in his works. Other than the probable likelihood that he studied with the Jesuits in Seville, Spain, that is all that is known about his education.

In 1570, Cervantes joined the Spanish forces at Naples, Italy. At this time, the Ottoman Empire and the Mediterranean countries were at war over control of land and power. As a soldier he witnessed the naval victory at the Gulf of Lepanto, Greece, on October 7, 1571. Aboard the Marquesa, in the thick of the battle, he was wounded twice in the chest and once in the left hand. The last wound maimed his hand for life. Cervantes often mentioned this victory in his works.

While in Tomar, Portugal, in 1581, Cervantes was given money to accomplish a royal mission to Oran. This he did, but the royal service was not very rewarding. About this same time, Cervantes turned to writing for the theater, an activity that guaranteed a certain income if the plays were successful. In the Adjunta to his Viaje del Parnaso (1614) and in the prologue to his Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses (1615), he tells of his dramatic successes and his eventual downfall. In a manuscript discovered in 1784, it was learned that of these early plays only two have survived: Los tratos de Argel and La Numancia.

In 1587, Cervantes was in Seville, Spain. The war between Spain and England was gearing up. The preparation of the Spanish Armada for its disastrous expedition against England was happening on a grand scale. But his new post as commander of the navy brought him only grief, shame and discomfort. As he had before, he turned to the theater for financial help. Cervantes agreed to write six plays, but payment would be withheld if the producer did not find each of the plays to be “one of the best ever produced in Spain.” Nothing is known of the outcome of this contract. For the next seven years, Cervantes was in and out of jail for bad financial deals.

Little documentation for the years from 1600 to 1603 exists. It is very probable that Cervantes was jailed again for financial reasons. Most of his time must have been taken up by the writing of Don Quixote. In January 1605, Don Quixote was published in Madrid. It was an immediate success.

When Cervantes was 65 years old he entered a period of extraordinary literary creativity. His Novelas ejemplares were published in Madrid in 1613. They are 12 little masterpieces, with which Cervantes created the art of short story writing in Spain.

In 1614, his poem, “Viaje del Parnaso,” was published. Later in 1615 Cervantes published his own second part of Don Quixote. Cervantes then put all of his energy into finishing Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, a novel of adventures. He had probably begun it at the turn of the century. He signed the dedication to the Count of Lemos (dated April 19, 1616) on his deathbed.

He died four days later in Madrid.

Source: http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ca-Ch/Cervantes-Miguel-de.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Wu Ch’eng-en

Wu Ch’eng-en

c. 1500-1582

Wu Cheng’en (ca. 1500-1582) was a Chinese novelist and poet of the Ming Dynasty, best known for being the attributed author of Journey to the West.

Wu was born in Lianshui, in Jiangsu province, and later moved to nearby Huaian. Wu’s father, Wu Rui, had had a good primary education and “shown an aptitude for study,” but ultimately spent his life as an artisan because of his family’s financial difficulties. Nevertheless, Wu Rui continued to “devote himself to literary pursuits” and, as a child, Wu acquired the same enthusiasm for literature – including classical literature, popular stories and anecdotes.

He took the imperial examinations several times in attempt to become a mandarin, or imperial, official but never passed and did not gain entry into the imperial university in Nanjing until middle age; after that, he did become an official and had postings in both Beijing and Changxing County, but he did not enjoy his work and eventually resigned, probably spending the rest of his life writing stories and poems in his hometown.

During this time he became an accomplished writer, producing both poetry and prose, and became friends with several prominent contemporary writers. Wu remained poor throughout his life, however, and did not have any children; dissatisfied with the political climate of the time and with the corruption of the world, he spent much of his life as a hermit.

Wu is best known for writing Journey to the West, one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature. Wu is widely thought to have published the work in anonymity due to the social pressures at the time. At the time when Wu lived, there was a trend in Chinese literary circles to imitate the classical literature of the Qin, Han and Tang dynasties, written in Classical Chinese; late in life, however, Wu went against this trend by apparently writing the novel, Journey to the West, in the vernacular tongue.

In addition to Journey to the West, Wu wrote numerous poems and stories (including the novel Yuding Animals, which includes a preface by Wu), although most have been lost. Some of his work survives because, after his death, a family member gathered as many manuscripts as he could find and compiled them into four volumes, entitled Remaining Manuscripts of Mr. Sheyang.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Cheng%27en

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Patrick Chamoiseau

Patrick Chamoiseau

1953-

Patrick Chamoiseau is a French author from Martinique known for his work in the creolite movement.

Chamoiseau was born on December 3, 1953 in Fort-de-France, Martinique, where he currently resides. After he studied law in Paris he returned to Martinique inspired by Edouard Glissant to take a close interest in Creole culture.

Chamoiseau is the author of a historical work on the Antilles under the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte and several nonfiction books, including Eloge de la creolite (In Praise of Creoleness), co-authored with Jean Bernabe and Raphael Confiant. His novel, Texaco, was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1992 and was chosen as a New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

Chamoiseau may also safely be considered as one of the most innovative writers to hit the French literary scene since Louis-Ferdinand Celine. His freeform use of French language – a highly complex yet fluid mixture of constant invention and “creolism” – fuels a poignant and sensuous depiction of Martinique people in particular and humanity at large.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Chamoiseau

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Raymond Chandler

Raymond Chandler

1888-1959

Raymond Thornton Chandler (July 23, 1888-March 26, 1959) was an American novelist and screenwriter.

Chandler was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1888, but spent his early years in Plattsmouth, Nebraska, living with his mother and father near his cousins, maternal aunt and uncle. After Chandler’s family were abandoned by his father, an alcoholic civil engineer who worked for the railway, and to obtain the best possible education for Ray, his mother moved them to London, England, in 1900. Another uncle, a successful Quaker lawyer in Waterford, supported them, while they lived with his maternal grandmother.

Chandler was classically educated at Dulwich College. He spent some of his childhood summers in Waterford with his maternal family. He did not attend university, instead spending time in Paris and Munich improving his foreign language skills. In 1907, he was naturalized as a British subject in order to take the civil service examination, which he passed, and then took an Admiralty job, lasting a year. His first poem was published during that time. Chandler regained his U.S. citizenship in 1956.

Chandler disliked the servility of the civil service and resigned, to the consternation of his family, and became a reporter for The Daily Express and The Bristol Western Gazette newspapers. He was an unsuccessful journalist, published reviews and continued writing romantic poetry.

In 1912, he borrowed money from his Waterford uncle, who expected it to be repaid with interest, and returned to America, visiting his aunt and uncle before settling in San Francisco for a time, where he took a correspondence bookkeeping course, finishing ahead of schedule. His mother joined him in late 1912 and they moved to Los Angeles in 1913. In 1917, when the U.S. entered World War I, he enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, saw combat in the trenches in France with the Gordon Highlanders and was undergoing flight training in the fledgling Royal Air Force (RAF) when the war ended.

Due to his meager financial circumstances during the Depression, Chandler turned to his latent writing talent to earn a living. Chandler’s first professional work, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” was published in Black Mask magazine in 1933; his first novel, The Big Sleep, was published in 1939, featuring his famous Philip Marlowe detective character speaking in the first person.

His second Marlowe novel, Farewell, My Lovely (1940), became the basis for three movie versions adapted by other screenwriters, including 1944’s Murder My Sweet. Literary success and film adaptations led to a demand for Chandler himself as a screenwriter. He and Billy Wilder co-wrote Double Indemnity (1944), based on James M. Cain’s novel of the same name. Chandler’s only original screenplay was The Blue Dahlia (1946). Chandler also collaborated on the screenplay of Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951).

In 1946, Chandler moved to La Jolla, California, an affluent coastal neighborhood of San Diego, where he wrote the final two Philip Marlowe novels, The Long Goodbye and his last completed work, Playback. Chandler’s final Marlowe short story, circa 1957, was entitled “The Pencil.”

Chandler’s loneliness worsened his propensity for clinical depression; he returned to drink, never quitting it for long, and the quality and quantity of his writing suffered. After a respite in England, he returned to La Jolla. He died at Scripps Memorial Hospital of pneumonial peripheral vascular shock and prerenal uremia in 1959.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Chandler

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Ellery Channing

William Ellery Channing

1780-1842