Author Biographies 25

Laura Ingalls Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder

1867-1957

Laura Wilder was born on February 7, 1867, in Lake Pepin, Wisconsin. She grew up in a family that moved frequently from one part of the American frontier to another. Her father took the family by covered wagon to Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Indian Territory and Dakota Territory. At age 15, she began teaching in rural schools. In 1885, she married Almanzo J. Wilder, with whom she lived from 1894 on a farm near Mansfield, Missouri. Some years later, she began writing for various periodicals. She contributed to McCall’s Magazine and Country Gentleman, served as poultry editor for The St. Louis Star and, for 12 years, was home editor of The Missouri Ruralist.

Prompted by her daughter, Wilder began writing down her childhood experiences. Her stories centered on the male unrest and female patience of pioneers in the mid-1800s and celebrated their peculiarly American spirit and independence. In 1932, she published Little House in the Big Woods, which was set in Wisconsin. After writing Farmer Boy (1933), a book about her husband’s childhood, she published Little House on the Prairie (1935), a reminiscence of her family’s stay in Indian Territory. The Little House books were well received by the reading public and critics alike; their warm, truthful portrayal of a life made picturesque by its very simplicity charmed generations of readers.

Wilder continued the story of her life in On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937), By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939), The Long Winter (1940), Little Town on the Prairie (1941) and These Happy Golden Years (1943). Her books remain in print.

She died on February 10, 1957 in Mansfield, Missouri.

Source: http://www.biography.com/people/laura-wilder-9531246

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

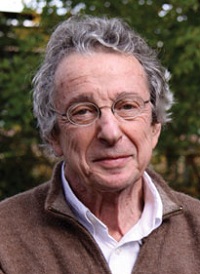

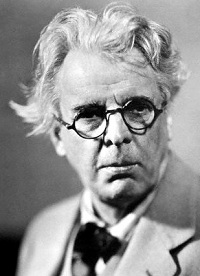

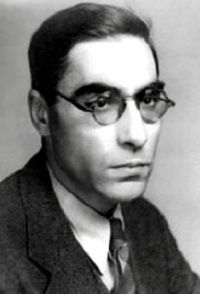

Thornton Wilder

Thornton Wilder

1897-1975

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897-December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and dramatist.

Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin, the son of Amos Parker Wilder, a U.S. diplomat, and Isabella Niven Wilder. His family lived for a time in China, where his sister, Janet, was born in 1910. He attended the English China Inland Mission Chefoo School at Yantai but returned with his mother and siblings to California in 1912 because of the unstable political conditions in China at the time. Thornton also attended Creekside Middle School in Berkeley and graduated from Berkeley High School in 1915. He also studied law for two years before dropping out of Purdue University.

After serving in the U.S. Coast Guard during World War I, he attended Oberlin College before earning his Bachelor of Arts degree at Yale University in 1920. He earned his Master of Art degree in French from Princeton University in 1926.

In 1926, Wilder’s first novel, The Cabala, was published. In 1927, The Bridge of San Luis Rey brought him commercial success and his first Pulitzer Prize in 1928. In 1938, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his play, Our Town, and he won the prize again in 1942 for his play, The Skin of Our Teeth.

World War II saw him rise to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Air Force Intelligence, first in Africa, then in Italy, until 1945. He went on to be a visiting professor at the University of Hawaii and to teach poetry at Harvard. In 1955, Wilder reworked The Merchant of Yonkers into The Matchmaker.

In 1967, he won the National Book Award for his novel, The Eighth Day. In his novel, The Ides of March (1948), he reflected on parallels between Benito Mussolini and Caesar. In 1962, he lived temporarily in the small town of Douglas, Arizona, where he started to write his longest novel, The Eighth Day. The book went on to win the National Book Award. His last novel, Theophilus North, was published in 1973.

He died on December 7, 1975, age 78, in Hamden, Connecticut, where he lived for many years with his sister, Isabel.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thornton_Wilder

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

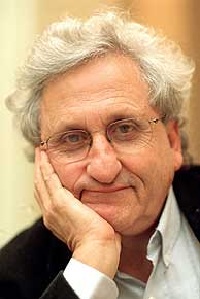

C.K. Williams

C.K. Williams

1936-2015

Charles Kenneth Williams (November 4, 1936-September 20, 2015) was an American poet. Senior poet Paul Muldoon described him as “one of the most distinguished poets of his generation.”

Williams grew up in Newark, New Jersey, and graduated from Columbia High School in Maplewood. He later studied at Bucknell University and the University of Pennsylvania. During this time, he spent five lonely months in Paris trying to write before realizing he knew nothing about poetry. He returned to Pennsylvania determined to learn something of poetry and began his writing career. He launched himself as a vehement anti-war poet at during the U.S. conflicts in southeast Asia. His first collection, Lies, was politically engaged; 1972 saw his first collection of explicitly anti-war poems.

He began teaching in 1975, first at a Y.M.C.A. in Philadelphia, later at Drexel University and then at the Franklin & Marshall College.

He won nearly every major poetry award. Flesh and Blood won the National Book Critics Circle Award. Repair (1999) won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, was a National Book Award finalist and won The Los Angeles Times Book Prize. The Singing won the National Book Award in 2003. In 2005, he was awarded the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Since 1996, he taught in the creative writing program at Princeton University and divided his time between Princeton and France.

Williams died of multiple myeloma on September 20, 2015 at his home in Hopewell, New Jersey.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._K._Williams

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Helen Maria Williams

Helen Maria Williams

1761/2-1827

Helen Maria Williams (1761/62-1827) was a British novelist, poet and translator of French-language works. A religious dissenter, she was a supporter of abolitionism and of the ideals of the French Revolution; she was imprisoned in Paris during the Reign of Terror but nonetheless spent much of the rest of her life in France.

She was born to a Scottish mother, Helen Hay, and a Welsh army officer father, Charles Williams. Sources variously give her birth as 1761 or 1762. Her father died when she was eight; the remnant of the family moved to Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Her 1786 Poems touch on topics ranging from religion to a critique of Spanish colonial practices. She allied herself with the cult of feminine sensibility, deploying it politically in opposition to war (“Ode on the Peace,” a 1786 poem about Peru) and slavery (the abolitionist “Poem on the Bill Lately Passed for Regulating the Slave Trade,” 1788).

In the context of the Revolution Controversy, she came down on the side of the revolutionaries in her 1790 novel, Julia, and defied convention by traveling alone to revolutionary France. Her letters from France marked a turn from being primarily a writer of poetry to one of prose. In France in July 1791, she published a poem, “A Farewell for Two Years to England.”

After the September Massacres of 1792, she allied herself with the Girondists; as a saloniere, she also hosted Mary Wollstonecraft, Francisco de Miranda and Thomas Paine. After the violent downfall of the Gironde and the rise of the Reign of Terror, she and her family were thrown into in the Luxembourg prison, where she was allowed to continue working on translations of French-language works into English, including what would prove to be a popular translation of Bernardin St. Pierre’s novel, Paul et Virginie. Upon her release, she traveled Switzerland. Her few poems from this period continue to express dissenting piety and were published in volumes with those of other religiously like-minded poets. In 1798, she published A Tour in Switzerland, which included an account of her travels, political commentary and the poem, “A Hymn Written amongst the Alps.”

Williams’ 1801 Sketches of the State of Manners and Opinions in the French Republic showed a continued attachment to the original ideals of the French Revolution but a growing disenchantment with the rise of Napoleon. After the Bourbon Restoration, she became a naturalized French citizen in 1818; nonetheless, in 1819, she moved to Amsterdam to live with a nephew she had helped raise.

She soon returned to Paris where, until her death in 1827, she continued to be an important interpreter of French intellectual currents for the English-speaking world.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_Maria_Williams

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Williams

John Williams

1664-1729

John Williams (December 10, 1664-June 12, 1729) was a New England Puritan minister who became famous for The Redeemed Captive, his account of his captivity by the Mohawk after the Deerfield Massacre during Queen Anne’s War. He was an uncle of the notable pastor and theologian, Jonathan Edwards. His first wife, Eunice Mather, was a niece of Rev. Increase Mather, a cousin of Rev. Cotton Mather and was related to Rev. John Cotton.

Williams was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony, to Samuel Williams (1632-98) and Theoda Park (1637-1718). His grandfather, Robert, had immigrated there from England in about 1638. Williams had local schooling; later, he attended Harvard College, where he graduated in 1683.

Williams was ordained to the ministry in 1688 and settled as the first pastor in Deerfield. The frontier town in western Massachusetts was vulnerable to the attacks of the Native Americans and their French allies from Canada. The local Pocumtuc resisted the colonists’ encroachment on their hunting grounds and agricultural land. In the early 18th century, French and English national competition resulted in frequent raids between New England and Canada, with each colonial power allying with various Native American tribes to enlarge their fighting forces.

In 1702, with the outbreak of Queen Anne’s War, New England colonists had taken prisoner a successful French pirate, Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste. To gain his return, the French governor of Canada planned to raid Deerfield, in alliance with the Mohawk of the Iroquois, Abenaki from northeast New England and the Pocumtuc. They intended to capture a prisoner of equal value to exchange. Raiding Deerfield, they captured Williams, prominent in the community, and more than 100 other English settlers.

On the night of February 28, 1704, approximately 300 French and Indian soldiers took 109 citizens captive, besides killing a total of 56 men, women and children, including two of Williams’ children and his African slave, Parthena. The raiding party led the Williams and other families on a march over 300 miles of winter landscape to Canada. En route to Quebec, a Mohawk killed Williams’ wife after she fell while trying to cross a creek, along with Frank, another African slave. Others of the most vulnerable older and youngest people died, some at the hands of Indians who judged them unable to go on. Williams remained steadfast and encouraged the other captives with prayer and Scripture along their journey to Quebec. The large party had seven weeks of hard overland travel to reach Fort Chambly.

While captive, Williams recorded his impressions of French colonial life in New France; Jesuit missionaries included him at their table for meals and he was often given comfortable lodgings, including a feather bed. Upon Pierre Maisonnat’s release from Boston, Williams was released by Quebec Governor Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil and returned to Boston on November 21, 1706, along with about 60 other captives. Among them were four of his children.

Williams and his children returned to Deerfield and resumed his pastoral charge in the latter part of 1706. He published several sermons and a narrative of his captivity called The Redeemed Captive (1707). He died in Deerfield in 1729.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Williams_%28minister%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Roger Williams

Roger Williams

1603?-1683

Roger Williams was born in London, circa 1603, the son of James and Alice (Pemberton) Williams. James, the son of Mark and Agnes (Audley) Williams, was a “merchant Tailor” (an importer and trader) and probably a man of some importance. His will, proved November 19, 1621, left, in addition to bequests to his “loving wife, Alice,” to his sons, Sydrach, Roger and Robert, and to his daughter, Catherine, money and bread to the poor in various sections of London.

Williams’ youth was spent in the parish of “St. Sepulchre’s, without Newgate, London.” While a young man, he must have been aware of the numerous burnings at the stake of so-called Puritans or heretics that had taken place at nearby Smithfield. This probably influenced his later strong beliefs in civic and religious liberty.

During his teens, Williams came to the attention of Sir Edward Coke, a brilliant lawyer and one-time Chief Justice of England, through whose influence he was enrolled at Sutton’s Hospital, a part of Charter House, a school in London. He next entered Pembroke College at Cambridge University, from which he graduated in 1627. All of the literature currently available at Pembroke to prospective students mentions Roger Williams, his part in the Reformation and his founding of the Colony of Rhode Island. At Pembroke, he was one of eight granted scholarships based on excellence in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Pembroke College in Providence, once the women’s college of Brown University, was named after Pembroke at Cambridge in honor of Roger Williams.

In the years after he left Cambridge, Roger Williams was Chaplain to a wealthy family and, on December 15, 1629, he married Mary Barnard at the Church of High Laver, Essex, England. Even at this time, he became a controversial figure because of his ideas on freedom of worship. And so, in 1630, 10 years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Roger thought it expedient to leave England. He arrived, with Mary, on February 5, 1631, at Boston in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Their passage was aboard the ship Lyon (Lion).

He preached first at Salem, then at Plymouth, then back to Salem, always at odds with the structured Puritans. When he was about to be deported back to England, Roger fled southwest out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was befriended by local Indians and eventually settled at the headwaters of what is now Narragansett Bay, after he learned that his first settlement on the east bank of the Seekonk River was within the boundaries of the Plymouth Colony. Roger purchased land from the Narragansett Chiefs, Canonicus and Miantonomi, and named his settlement Providence in thanks to God. The original deed remains in the Archives of the City of Providence.

Williams made two trips back to England during his lifetime. The first in June or July 1643 was to obtain a Charter for his colony to forestall the attempt of neighboring colonies to take over Providence. He returned with a Charter for “the Providence Plantations in Narragansett Bay,” which incorporated Providence, Newport and Portsmouth. During this voyage, he produced his best-known literary work, Key into the Languages of America which, when published in London in 1643, made him the authority on American Indians.

On his return, Williams started a trading post at Cocumscussoc (now North Kingstown) where he traded with the Indians and was known for his peacemaking between the neighboring colonists and the Indians. But again colony affairs interfered and, in 1651, he sold his trading post and returned to England with John Clarke (a Newport preacher) in order to have the Charter confirmed. Because of family responsibilities, he returned sometime before 1654.

Williams was Governor of the Colony from 1654 through 1658. During the later years of his life, almost all of Providence burned during King Philip’s War, 1675-1676. He lived to see Providence rebuilt. He continued to preach and the Colony grew through its acceptance of settlers of all religious persuasions.

Roger Williams died at Providence between January 16 and April 16, 1683/84.

Source: http://www.rogerwilliams.org/biography.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Tennessee Williams

Tennessee Williams

1911-1983

Tennessee Williams was born Thomas Lanier Williams III in Columbus, Mississippi, on March 26, 1911, to Cornelius Williams, a traveling salesman, and the former Edwina Dakin. He first began to write while afflicted with paralysis as a child, which affected him between the ages of five and seven, turning him into an invalid for two years. At the age of 13, his mother – who encouraged his writing – gave him a typewriter.

Williams wrote his first play, Cairo, Shanghai, Bombay!, when he was a teenager, in 1935. He became a published writer at the age of 16, winning third prize (and $5) for his essay, “Can a Good Wife Be a Good Sport?” in a contest sponsored by the magazine, Smart Set. The magazine Weird Tales published his short story, “The Vengeance of Nitocris,” in 1928.

When Williams was 17, the family moved to St. Louis. He went to the University of Missouri-Columbia for his higher education, where his fraternity brothers gave him the nickname “Tennessee” due to his deep Southern accent. Later, he transferred to Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, but did not take his degree until he was 28 years old, from the University of Iowa, where he matriculated in the school’s writing program.

His first play, A Battle of Angels, failed in Boston during tryouts in 1940. Though the play failed, it made Williams known and he worked as a contract writer, briefly, for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

The failure of The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Any More (1963) signaled the end of Williams’ greatness as a dramatist and his dominance of Broadway theater. His next original Broadway production, Slapstick Tragedy (an omnibus of two short plays), closed after seven performances in 1966. The Seven Descents of Myrtle, another original, lasted but 29 performances in 1968. Outcry lasted only 12 performances in 1973, while the dual bill of A Memory of Two Mondays and 27 Wagons Full of Cotton lasted 63 performances in 1976, but The Eccentricities of a Nightingale closed after 24 performances and Vieux Carre didn’t last a week, closing after six performances in 1977. The last Broadway original produced during Williams’ lifetime, Clothes for a Summer Hotel, lasted just 14 performances in 1980.

Two Broadway originals have been produced posthumously: Garden District, consisting of Something Unspoken and Suddenly, Last Summer, which ran for 31 performances in 1995; and the early play, Not about Nightingales, which ran for 125 performances in 1999 and was nominated for a Best Play Tony.

Tennessee Williams died on February 25, 1983, after choking on the cap of a bottle of eye drops that became lodged in his throat.

Source: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0931783/bio

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams

1883-1963

William Carlos Williams (September 17, 1883-March 4, 1963) was an American poet closely associated with Modernism and Imagism. He was also a pediatrician and general practitioner of medicine.

Williams was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, to an English father and a Puerto Rican mother. He received his primary and secondary education in Rutherford until 1897, when he was sent for two years to a school near Geneva and to the Lycee Condorcet in Paris. He attended the Horace Mann School upon his return to New York City and, after having passed a special examination, he was admitted in 1902 to the medical school of the University of Pennsylvania, from which he graduated in 1906. He published his first book, Poems, in 1909.

Williams married Florence Herman (1891-1976) in 1912, after his first proposal to her older sister was refused. They moved into a house in Rutherford, New Jersey, which was their home for many years. Shortly afterward, his second book of poems, The Tempers, was published by a London press through the help of his friend, Ezra Pound, whom he met while studying at the University of Pennsylvania.

Although his primary occupation was as a family doctor, Williams had a successful literary career as a poet. In addition to poetry, he occasionally wrote short stories, plays, novels, essays and translations. He practiced medicine by day and wrote at night.

In 1920, Williams was sharply criticized when he published one of his most experimental books, Kora in Hell: Improvisations. A few years later, Williams published one of his seminal books of poetry, Spring and All, which contained classic Williams poems like, “By the Road to the Contagious Hospital,” “The Red Wheelbarrow” and “To Elsie.”

In his modernist epic collage of place, “Paterson” (published between 1946 and 1958), an account of the history, people and essence of Paterson, New Jersey, he tried to write his own Modernist epic poem, focusing on “the local” on a wider scale than he had previously attempted.

After Williams suffered a heart attack in 1948, his health began to decline and, after 1949, a series of strokes followed. Williams died on March 4, 1963 at the age of 79 at his home in Rutherford. He was buried in Hillside Cemetery in Lyndhurst, New Jersey.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Carlos_Williams

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Wilmot (2nd Earl of Rochester)

John Wilmot (2nd Earl of Rochester)

1647-1680

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, English poet and wit, was the son of Henry Wilmot, 1st Earl (c. 1612-1658). He was born in Oxfordshire on April 1, 1647, and died there on July 26, 1680.

Rochester’s mother was Parliamentarian by descent and inclined to Puritanism for possibly expedient means. His father, a hard-drinking Royalist from Anglo-Irish stock, had been created Earl of Rochester in 1652 for military services to Charles II during his exile under the Commonwealth; he died abroad in 1658, two years before the restoration of monarchy in England.

At 12, Rochester matriculated at Wadham College, Oxford, and there, it is said, “grew debauched.” At 14, he was conferred with the degree of M.A. by the Earl of Clarendon, who was Chancellor to the University and Rochester’s uncle. After a tour of France and Italy, Rochester returned to London, where he was to grace the Restoration Court. Courage in sea battle against the Dutch made him a hero.

In 1667, he married Elizabeth Malet, a witty heiress whom he had attempted to abduct two years earlier.

Rochester’s life is divided between domesticity in the country and a riotous existence at Court, where he was renowned for drunkenness, vivacious conversation and “extravagant frolics” as part of the Merry Gang, who flourished for about 15 years after 1665. In banishment from Court for a scurrilous lampoon on Charles II, Rochester set up as “Doctor Bendo,” a physician skilled in treating barrenness; his practice was, it is said, “not without success.” Deeply involved with theatre, his coaching of his mistress Elizabeth Barry began her career as the greatest actress of the Restoration stage.

At the age of 33, as Rochester lay dying (from syphilis, it is assumed) his mother had him attended by her religious associates; a deathbed renunciation of atheism was published and promulgated as the conversion of a prodigal. This became legendary, reappearing in numerous pious tracts over the next two centuries.

Rochester’s own writings were at once admired and infamous. Posthumous printings of his play, Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery, gave rise to prosecutions for obscenity and were destroyed. During his lifetime, his songs and satires were known mainly from anonymous broadsheets and manuscript circulation; most of Rochester’s poetry was not published under his name until after his death.

Source: http://www.druidic.org/roc-bio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

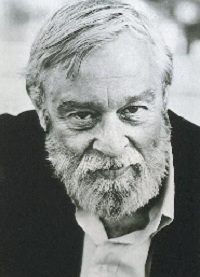

August Wilson

August Wilson

1945-2005

Born on April 27, 1945, August Wilson grew up in the Hill district of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His childhood experiences in this black slum community would later inform his dramatic writings, including his first produced play, Black Bart and the Sacred Hills, which was staged in 1981.

Then, in 1984, August Wilson was catapulted to the forefront of the American theatre scene with the success of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, produced at Yale and later in New York in 1984. The play was voted Best Play of the Year (1984-85) by the New York Drama Critics’ Circle.

Wilson continued to work in close collaboration with Lloyd Richards of the Yale School of Drama and, by early 1990s, had established himself as the best-known and most-popular African-American playwright.

Wilson also set for himself a daunting task to write a 10-play cycle that chronicles each decade of the black experience in the 20th century. Each of Wilson’s plays is a chapter in this remarkable cycle of plays and focuses on what Wilson perceives as the largest issue to confront African-Americans in that decade.

His second play, Fences, opened on Broadway in the spring of 1987 to enormous critical acclaim and earned Wilson his first Pulitzer Prize.

In April 1988, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone opened on Broadway, again to enormous critical acclaim.

The Piano Lesson was named Best Play of the Year by the New York Drama Critics’ Circle. It also earned Wilson his second Pulitzer Prize for Drama, as well as a Drama Desk Award.

In April 2005, Wilson finally completed his 10-play cycle when Radio Golf premiered at the Yale Repertory Theatre. Two months later, he was diagnosed with liver cancer and, on October 2, 2005, August Wilson passed away at the age of 60.

Source: http://www.imagi-nation.com/moonstruck/clsc48.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Harriet Wilson

Harriet Wilson

1825-1900

Harriet E. “Hattie” Adams Wilson (March 15, 1825-June 28, 1900) is traditionally considered the first female African-American novelist as well as the first African-American of any gender to publish a novel on the North American continent. Her novel, Our Nig, was published in 1859 and rediscovered in 1982.

Adams was born in Milford, New Hampshire, the daughter of Joshua Green, an African-American “hooper of barrels,” and Margaret Ann (or Adams) Smith, a washerwoman of Irish ancestry. Her father died when she was very young and her mother abandoned her at the farm of Nehemiah Hayward Jr., a well-to-do Milford farmer. As an orphan, Adams was made an indentured servant to the Hayward family, a customary way for society to arrange support at the time. In exchange for her labor, the child would receive room, board and training in life skills, or that was the ideal.

After the end of her indenture, Hattie Adams (as she was then known) worked as a house servant and a seamstress in households in southern New Hampshire and in central and western Massachusetts. She married Thomas Wilson in Milford on October 6, 1851.

Thomas abandoned Harriet soon after they married. Pregnant and ill, Wilson was sent to the Hillsborough County Poor Farm in Goffstown, New Hampshire, where her only son, George Mason Wilson, was born. His probable birth date was June 15, 1852. Soon after George’s birth, Thomas Wilson reappeared in her life and took her and her son away from the Poor Farm. Thomas Wilson returned to sea and died soon after. Harriet Wilson returned her son to the care of the Poor Farm, where he died in 1860 at the age of seven.

She moved to Boston, Massachusetts. While in Boston, Wilson wrote Our Nig. On August 18, 1859, she copyrighted it and a copy of the novel was deposited in the Office of the Clerk of the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts.

From 1867 to 1897, “Mrs. Hattie E. Wilson” was listed in the Banner of Light as a trance reader and lecturer. She spoke at camp meetings, in theaters and in private homes throughout New England.

Closer to home, Wilson was active in the organization and maintenance of Children’s Progressive Lyceums, the Spiritualist church equivalent to Sunday Schools; she organized Christmas celebrations; she participated in skits and playlets; at meetings she sometime sang as part of a quartet; she was also known for her floral centerpieces and the candies and confections she would make for the children were long remembered.

When she was not pursuing Spiritualistic activities, Wilson was employed as a nurse and healer (“clairvoyant physician”). For nearly 20 years, from 1879 to 1897, she was the housekeeper of a boardinghouse in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street. She rented out rooms, collected rents and provided basic maintenance. Despite Wilson’s active and fruitful life after Our Nig, there is no evidence that she ever wrote anything else for publication.

On June 28, 1900, “Hattie E. Wilson” died in the Quincy Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harriet_E._Wilson

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Jeanette Winterson

Jeanette Winterson

1959-

Jeanette Winterson (born August 27, 1959) is a British novelist.

Winterson was born in Manchester and adopted on January 21, 1960. She was raised in Accrington, Lancashire, by Constance and John William Winterson. She was raised in the Elim Pentecostal Church and, intending to become a Pentecostal Christian missionary, she began evangelizing and writing sermons at age six.

By age 16, she left home and attended Accrington and Rossendale College, supporting herself at a variety of odd jobs while reading for a degree in English at St. Catherine’s College, Oxford.

After moving to London, her first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, won the 1985 Whitbread Prize for a First Novel. She won the 1987 John Llewellyn Rhys Prize for The Passion, a novel set in Napoleonic Europe.

Winterson’s subsequent novels explore the boundaries of physicality and the imagination, gender polarities and sexual identities and have won several literary awards. Her stage adaptation of The PowerBook in 2002 opened at the Royal National Theatre, London.

Winterson was made an officer of Order of the British Empire (OBE) at the 2006 New Year Honours.

In 2009, she donated the short story, “Dog Days,” to Oxfam’s Ox-Tales project comprising four collections of UK stories written by 38 authors. Winterson’s story was published in the “Fire” collection.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeanette_Winterson

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Winthrop

John Winthrop

1588-1649

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/8-March 26, 1649) was a wealthy English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the first major settlement in New England after Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the first large wave of migrants from England in 1630 and served as governor for 12 of the colony’s first 20 years of existence. His writings and vision of the colony as a Puritan “city upon a hill” dominated New England colonial development, influencing the government and religion of neighboring colonies.

Born into a wealthy landowning and merchant family, Winthrop was trained in the law and became Lord of the Manor at Groton in Suffolk. Although he was not involved in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1628, he became involved in 1629 when the anti-Puritan King Charles I began a crackdown on Nonconformist religious thought. In October 1629, he was elected governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and, in April 1630, he led a group of colonists to the New World, founding a number of communities on the shores of Massachusetts Bay and the Charles River.

Between 1629 and his death in 1649, he served 12 annual terms as governor and was a force of comparative moderation in the religiously conservative colony, clashing with the more conservative Thomas Dudley and the more liberal Roger Williams and Henry Vane. Although Winthrop was a respected political figure, his attitude toward governance was somewhat authoritarian: He resisted attempts to widen voting and other civil rights beyond a narrow class of religiously approved individuals, opposed attempts to codify a body of laws that the colonial magistrates would be bound by and also opposed unconstrained democracy, calling it “the meanest and worst of all forms of government.” The authoritarian and religiously conservative nature of Massachusetts rule was influential in the formation of neighboring colonies, which were in some instances formed by individuals and groups opposed to the rule of the Massachusetts elders.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Winthrop

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Owen Wister

Owen Wister

1860-1938

Owen Wister, the “Father” of western fiction, was born on July 14, 1860, in Germantown, a neighborhood within the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His father, Owen Jones Wister, was a wealthy physician, one of a long line of Wisters raised at the storied Belfield estate in Germantown. His mother, Sarah Butler Wister, was the daughter of actress Fanny Kemble.

He briefly attended schools in Switzerland and Britain and later studied at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, and Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he was a classmate of Theodore Roosevelt, an editor of The Harvard Lampoon and a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon (Alpha chapter). Wister graduated from Harvard in 1882.

At first, he aspired to a career in music and spent two years studying at a Paris conservatory. Thereafter, he worked briefly in a bank in New York before studying law, having graduated from the Harvard Law School in 1888. Following this, he practiced with a Philadelphia firm but was never truly interested in that career. He was interested in politics, however, and was a staunch Theodore Roosevelt backer. In the 1930s, he opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Wister had spent several summers out in the American West, making his first trip to Wyoming in 1885. Like his friend Roosevelt, Wister was fascinated with the culture, lore and terrain of the region. On an 1893 visit to Yellowstone, Wister met the western artist Frederic Remington, who remained a lifelong friend.

When he started writing, he naturally inclined toward fiction set on the Western frontier. Wister’s most famous work remains the 1902 novel, The Virginian, the loosely constructed story of a cowboy who is a natural aristocrat, set against a highly mythologized version of the Johnson County War and taking the side of the large land owners. This is widely regarded as being the first cowboy novel and was reprinted 14 times in eight months. The book is dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1898, Wister married Mary Channing, his cousin. The couple had six children. Wister’s wife died during childbirth in 1913.

Wister died at his home in Saunderstown, Rhode Island. He is buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owen_Wister#Bibliography

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Amy Witting

Amy Witting

1918-2001

Amy Witting (January 26, 1918-September 18, 2001) was the pen name of an Australian novelist and poet born Joan Austral Fraser. She was widely acknowledged as one of Australia’s “finest fiction writers, whose work was full of the atmosphere and color or times past.”

Witting was born in the Sydney suburb of Annandale and was brought up as a Catholic. She suffered from tuberculosis as a child. She went to Fort Street Girls’ High School. She studied languages at the University of Sydney. Subsequently, she gained a Diploma of Education at Teachers College and became a school teacher. Her tuberculosis recurred in her early adulthood, resulting in her spending time in a sanatorium.

On July 28, 1934, when Witting was 16, one of her poems, written under the pseudonym De Guesclin, was published in The Sydney Morning Herald. Witting always wrote under a pseudonym. Her pen name, Amy Witting, is from a promise she made to herself to “never give up on consciousness, not be unwitting, but to always remain ‘witting.’”

Witting married Les Levick, a fellow high school teacher, in 1948, and they had one son. Greg.

She continued to write until her death, of cancer, a few weeks after the publication of After Cynthia, her last novel, in 2001.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amy_Witting

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Wolfe

Thomas Wolfe

1900-1938

Thomas Clayton Wolfe (October 3, 1900-September 15, 1938) was a major American novelist of the early 20th century.

Wolfe was born in Asheville, North Carolina, the youngest of eight children of William Oliver Wolfe (1851-1922) and Julia Elizabeth Westall (1860-1945). His father was a successful stone carver who ran a gravestone business. His mother took in boarders and was active in acquiring real estate. In 1904, she opened a boarding house in St. Louis for the World’s Fair.

Wolfe began to study at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) when he was 15 years old; he was a member of the Dialectic Society and Pi Kappa Phi fraternity and predicted that his portrait would one day hang in Old West near that of North Carolina governor Zebulon Vance, which it does today.

Wolfe’s first literary aspiration was to be a playwright and, in the fall of 1919, he enrolled in a playwriting course. His one-act play, The Return of Buck Gavin, was performed by the newly formed Carolina Playmakers, then composed of classmates in Frederick Koch’s playwriting class, with Wolfe acting the title role. He edited UNC’s student newspaper, The Daily Tar Heel, and won the Worth Prize for Philosophy for an essay, “The Crisis in Industry.” Another of his plays, The Third Night, was performed by the Playmakers in December 1919. Wolfe was inducted into the Golden Fleece honor society. In 1922, Wolfe received his master’s degree from Harvard.

Wolfe went to New York City in November 1923 and solicited funds for UNC while trying to sell his plays to Broadway. In February 1924, he began temporarily teaching English as an instructor at New York University (NYU), a position he occupied periodically for almost seven years.

Unable to sell any of his plays after three years due to their excessive length, including a close call when the Theatre Guild came very close to producing his play, Welcome to Our City, before ultimately rejecting it, Wolfe found his writing style more suited to fiction than the stage. He sailed to Europe in October 1924 to continue writing. In the summer of 1926, he began writing the first version of a novel, O Lost, which eventually evolved into Look Homeward, Angel. It was a bestseller in the United Kingdom and Germany.

After four more years writing in Brooklyn, the second novel Wolfe submitted to Scribner’s was The October Fair, a multi-volume epic. It was edited to create a single, bestseller-sized volume, Of Time and the River. This novel was more commercially successful than Look Homeward, Angel.

Wolfe had spent much time in Europe and was especially popular and at home in Germany, where he had many friends. However, in 1936, he witnessed discriminatory incidents toward Jewish people that upset him and changed his mind about the country. Wolfe returned to America and published a short story chronicling the incidents, called “I Have a Thing to Tell You,” in The New Republic. Following the publication, Wolfe’s books were banned by the German government and he was forbidden from traveling there.

On September 6, he was sent to Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital for treatment of military tuberculosis of the brain under the most famous neurosurgeon in the country, Dr. Walter Dandy, but an attempt at a life-saving operation revealed the disease had overrun the entire right side of his brain. Without regaining consciousness, he died 18 days before his 38th birthday.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Wolfe

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Tom Wolfe

Tom Wolfe

1931-2018

Tom Wolfe was born and raised in Richmond, Virginia. He was educated at Washington and Lee (B.A., 1951) and Yale (Ph.D, American Studies, 1957) universities. In December 1956, he took a job as a reporter on The Springfield (Massachusetts) Union. This was the beginning of a 10-year newspaper career, most of it spent as a general-assignment reporter. For six months in 1960 he served as The Washington Post’s Latin American correspondent and won the Washington Newspaper Guild’s foreign news prize for his coverage of Cuba.

In 1962, he became a reporter for The New York Herald-Tribune and, in addition, one of the two staff writers of New York magazine, which began as The Herald-Tribune’s Sunday Supplement. While still a daily reporter for The Herald-Tribune, he completed his first book, a collection of articles about the flamboyant 1960s written for New York and Esquire and published in 1965 as The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.

In 1968, he published two bestsellers on the same day: The Pump House Gang, made up of more articles about life in the 1960s, and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, a nonfiction story of the hippie era. In 1970, he published Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, a highly controversial book about racial friction in the United States.

Even more controversial was Wolfe’s 1975 book on the American art world, The Painted Word. In 1976, he published another collection, Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine, which included his well-known essay, “The Me Decade and the Third Great Awakening.”

In 1979, Wolfe completed a book he had been at work on for more than six years, an account of the rocket airplane experiments of the post-World War II era and the early space program, focusing upon the psychology of the rocket pilots and the astronauts and the competition between them. The Right Stuff became a bestseller and won the American Book Award for nonfiction, the National Institute of Arts and Letters Harold Vursell Award for prose style and the Columbia Journalism Award.

The book, In Our Time, published in 1980, featured his own illustrations of his work. In 1981, he wrote a companion to The Painted Word, entitled From Bauhaus to Our House, about the world of American architecture.

In 1984 and 1985, Wolfe wrote his first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, in serial form against a deadline of every two weeks for Rolling Stone magazine. It came out in book form in 1987.

In 1996, Wolfe wrote the novella, Ambush at Fort Bragg, as a two-part series for Rolling Stone. In 1997, it was published as a book. The novel, A Man in Full, was published in November 1998.

In October 2000, Wolfe published Hooking Up, a collection of fiction and nonfiction concerning the turn of the new century. In 2005, he published his novel, I Am Charlotte Simmons.

Wolfe lived in New York City with his wife, Sheila. He died from an infection on May 14, 2018, at the age of 88.

Source: http://www.tomwolfe.com/bio.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Tobias Wolff

Tobias Wolff

1945-

Tobias Jonathan Ansell Wolff (born June 19, 1945) is an American author. He is known for his memoirs, particularly This Boy’s Life (1989), and his short stories. He has also written two novels.

Wolff was born in 1945 in Birmingham, Alabama. After attending Concrete High School in Concrete, Washington, Wolff was accepted by The Hill School under the self-embellished name Tobias Jonathan von Ansell-Wolff III but he was later expelled. He served in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War era. He holds a First Class Honors degree in English from Hertford College, Oxford (1972), and an M.A. from Stanford University. In 1975, he was awarded a Wallace Stegner Fellowship in Creative Writing at Stanford.

Wolff is the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, where he has taught classes in English and creative writing since 1997. He also served as the director of the Creative Writing Program at Stanford from 2000 to 2002.

Wolff is best known for his work in two genres: the short story and the memoir. His first short story collection, In the Garden of the North American Martyrs, was published in 1981. The collection was well received and several of its stories have since reappeared in a number of anthologies.

Wolff’s 1984 novella, The Barracks Thief, won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction for 1985. In 1985, Wolff’s second short story collection, Back in the World, was published.

Wolff chronicled his early life in two memoirs. This Boy’s Life (1989) concerns itself with the author’s adolescence in Seattle and then in Newhalem, a remote company town in the North Cascade mountains of Washington State. In Pharaoh’s Army (1994) records Wolff’s U.S. Army tour of duty in Vietnam. A third collection of stories, The Night in Question, was published in 1997. Our Story Begins, a collection of new and previously published stories, appeared in 2008.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobias_Wolff

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft

1759-1797

Mary Wollstonecraft (April 27, 1759-September 10, 1797) was an 18th century British writer, philosopher and advocate of women’s rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book and a children’s book. Wollstonecraft is best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), in which she argues that women are not naturally inferior to men but appear to be only because they lack education. She suggests that both men and women should be treated as rational beings and imagines a social order founded on reason.

Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft’s life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationships, received more attention than her writing. After two ill-fated affairs, with Henry Fuseli and Gilbert Imlay (by whom she had a daughter, Fanny Imlay), Wollstonecraft married the philosopher William Godwin, one of the forefathers of the anarchist movement.

Wollstonecraft died at the age of 38, 10 days after giving birth to her second daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (later Mary Shelley), leaving behind several unfinished manuscripts.

After Wollstonecraft’s death, her widower published a Memoir (1798) of her life.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Wollstonecraft

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

1882-1941

Adeline Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882-March 28, 1941) was an English author, essayist, publisher and writer of short stories.

During the inter-war period, Woolf was a significant figure in London literary society and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Her most famous works include the novels, Mrs. Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) and Orlando (1928), and the book-length essay, “A Room of One’s Own” (1929).

Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen in London in 1882 to Sir Leslie Stephen and Julia Prinsep Stephen (nee Jackson). The sudden death of her mother in 1895, when Virginia was 13, and that of her half-sister, Stella, two years later, led to the first of Woolf’s several nervous breakdowns. She was, however, able to take courses of study in Greek, Latin, German and history at the Ladies’ Department of King’s College London between 1897 and 1901. The death of her father in 1904 provoked her most alarming collapse and she was briefly institutionalized. Throughout her life, Woolf was plagued by periodic mood swings and associated illnesses. Though this instability often affected her social life, her literary productivity continued with few breaks throughout her life.

She married writer Leonard Woolf on August 10, 1912. Despite his low material status, the couple shared a close bond. The two also collaborated professionally, in 1917 founding the Hogarth Press, which subsequently published Virginia’s novels along with works by T.S. Eliot, Laurens van der Post and others.

Woolf began writing professionally in 1900, initially for The Times Literary Supplement with a journalistic piece about Haworth, home of the Bronte family. Her first novel, The Voyage Out, was published in 1915. Woolf went on to publish novels and essays as a public intellectual to both critical and popular success.

After completing the manuscript of her last (posthumously published) novel, Between the Acts, Woolf fell into a depression similar to that which she had earlier experienced. The onset of World War II, the destruction of her London home during the Blitz and the cool reception given to her biography of her late friend, Roger Fry, all worsened her condition until she was unable to work.

On March 28, 1941, Woolf put on her overcoat, filled its pockets with stones, and walked into the River Ouse near her home and drowned herself.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Woolf

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Woolman

John Woolman

1720-1772

John Woolman (October 19, 1720-October 7, 1772) was an American itinerant Quaker preacher who traveled throughout the American colonies and in England, advocating against cruelty to animals, economic injustices and oppression, conscription, military taxation and, particularly, slavery and the slave trade.

Woolman came from a family of Friends (Quakers). His grandfather, also named John Woolman, was one of the early colonial settlers of New Jersey. His father, Samuel Woolman, was a farmer. Their estate was between Burlington and Mount Holly Township in that colony.

In his Journal, Woolman related a story about a major turning point in his life. During his youth, he happened upon a robin’s nest with hatchlings in it. Woolman, as many young people would do, began throwing rocks at the mother robin just to see if he could hit her. He ended up killing the mother bird, but then remorse filled him as he thought of the baby birds who had no chance of surviving without her. He got the nest down from the tree and quickly killed the hatchlings – believing it to be the most merciful thing to do. This experience weighed on his heart and inspired in him a love and protectiveness for all living things from then on.

At age 23, his employer asked him to write a bill of sale for a slave. Though he told his employer that he thought that slave-keeping was inconsistent with Christianity, he wrote the bill of sale. Later, he refused to write the part of a will that included disposing of a slave and in that case, convinced the man to set the slave free. Many Friends believed that slavery was bad – even a sin – but there was not a universal condemnation of it among Friends. Some Friends bought slaves from other people in order to treat them humanely and educate them. Other Friends seemed to have no conviction against slavery whatsoever.

Woolman took up a concern to minister to Friends and others in remote places. He went on his first ministry trip in 1746 with Isaac Andrews. They traveled about 1,500 miles round-trip in three months, going as far south as North Carolina. He preached on many topics, including slavery, during this and other such trips.

In 1754, Woolman wrote “Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes.” He subsequently refused to draw up wills transferring slaves. Working on a nonconfrontational, personal level, he individually convinced many Quaker slaveholders to free their slaves. He attempted personally to avoid using the products of slavery; for example, he wore undyed clothing because slaves were used in the making of dyes. He was also known in later life to abjure riding in stagecoaches, on grounds that their operation was too often cruel and injurious to their teams of horses.

In his lifetime, Woolman did not succeed in eradicating slavery even within the Society of Friends in colonial America; however, his personal efforts changed Quaker viewpoints. In 1790, the Society of Friends petitioned the United States Congress for the abolition of slavery. The fair treatment of people of all races is now part of the Friends’ Testimony of Equality. Woolman’s colonial-era success in persuading his fellow Quakers on this issue is credited with giving Quakers in the early days of the U.S. the moral authority to labor with people of other Christian traditions over it.

Woolman’s final journey was to England in 1772. During the voyage, he stayed in steerage and spent time with the crew rather than in the better accommodations of the other passengers. He attended the Britain London Yearly Meeting and Friends there were persuaded to oppose slavery in their Epistle (a type of letter sent to Quakers in other places.) Woolman went from London to York, where he died of smallpox. He was buried on October 9. A memorial to him is located in Mount Holly, New Jersey, on the site of one of his orchards, housed in a small home he reportedly built for his daughter and her husband.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Woolman

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Constance Fenimore Woolson

Constance Fenimore Woolson

1840-1894

Constance Fenimore Woolson (March 5, 1840-January 24, 1894) was an American novelist and short story writer. She was a grand-niece of James Fenimore Cooper and is best known for fictions about the Great Lakes region, the American South and American expatriates in Europe.

Woolson was born in Claremont, New Hampshire, but her family soon moved to Cleveland, Ohio, after the deaths of three of her sisters from scarlet fever. Woolson was educated at the Cleveland Female Seminary and a boarding school in New York. She traveled extensively through the midwestern and northeastern regions of the U.S. during her childhood and young adulthood.

Woolson’s father died in 1869 and, in the following year, she began to publish fiction and essays in magazines such as The Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Magazine. Her first full-length publication was a children’s book, The Old Stone House (1873) and, in 1875, she published her first volume of short stories, Castle Nowhere: Lake-Country Sketches, based on her experiences in the Great Lakes region, especially Mackinac Island.

From 1873 to 1879, Woolson wintered with her mother in St. Augustine, Florida. During these winter visits she traveled widely in the South, which gave her material for her next collection of short stories, Rodman the Keeper: Southern Sketches (1880). After her mother’s death in 1879, she went to Europe, staying at a succession of hotels in England, France, Italy, Switzerland and Germany.

In 1880, she met Henry James and the relationship between the two writers has prompted much speculation by biographers, especially Lyndall Gordon in her 1998 book, A Private Life of Henry James. Woolson’s most famous story, “Miss Grief,” has been read as a fictionalization of their friendship, though she had not yet met James when she wrote it. Recent novels such as Emma Tennant’s Felony (2002), David Lodge’s Author, Author (2004) and Colm Toibin’s The Master (2004) have treated with the still-unclear relationship between Woolson and James.

Woolson published her first novel, Anne, in 1880, followed by three others: East Angels (1886), Jupiter Lights (1889) and Horace Chase (1894). In 1883, she published the novella, For the Major, a story of the post-war South that has become one of her most respected fictions. In the winter of 1889-1890, she traveled to Egypt and Greece, which resulted in a collection of travel sketches, Mentone, Cairo and Corfu (published posthumously in 1896).

In 1893, Woolson rented an elegant apartment on the Grand Canal of Venice. Suffering from influenza and depression, she either jumped or fell to her death from a window in the apartment in January 1894. Two volumes of her short stories appeared after her death: The Front Yard and Other Italian Stories (1895) and Dorothy and Other Italian Stories (1896). She is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constance_Fenimore_Woolson

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

1770-1850

William Wordsworth was born April 7, 1770, in Cockermouth, Cumberland, to John and Anne (Cookson) Wordsworth, the second of their five children. His father was law agent and rent collector for Lord Lonsdale, and the family was fairly well off. After his mother’s death in 1778, he was sent to Hawkshead Grammar School, near Windermere; in 1787, he went up to St. John’s College, Cambridge.

In 1794, he was reunited with his sister, Dorothy, who became his companion, close friend, moral support and housekeeper until her physical and mental decline in the 1830s. William and Dorothy settled in his beloved Lake district, near Grasmere. The next year, he met Coleridge and the three of them grew very close, the two men meeting daily in 1797-98 to talk about poetry and to plan Lyrical Ballads, which was published in 1798.

Wordsworth’s literary career began with Descriptive Sketches (1793) and reached an early climax before the turn of the century with Lyrical Ballads. His powers peaked with Poems in Two Volumes (1807).

The important later works were well under way. His success with shorter forms made him the more eager to succeed with longer, specifically with a long, three-part “philosophical poem, containing views of Man, Nature, and Society … having for its principal subject the sensations and opinions of a poet living in retirement.” The 17,000 lines that were eventually published made up only a part of this mammoth project. The second section, The Excursion, was completed (published 1814), as was the first book of the first part, The Recluse. During his lifetime he refused to print The Prelude, which he had completed by 1805, because he thought it was unprecedented for a poet to talk as much about himself – unless he could put it in its proper setting, which was as an introduction to the complete three-part Recluse.

Durham University granted him an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1838 and Oxford conferred the same honor the next year. When Robert Southey died in 1843, Wordsworth was named Poet Laureate.

He died in 1850 and his wife published the much-revised Prelude that summer.

Source: http://www.victorianweb.org/previctorian/ww/bio.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

James Wright

James Wright

1927-1980

James Arlington Wright (December 13, 1927-March 25, 1980) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet.

Wright first emerged on the literary scene in 1956 with The Green Wall, a collection of formalist verse that was awarded the prestigious Yale Younger Poets Prize. But, by the early 1960s, Wright, increasingly influenced by the Spanish-language surrealists, had dropped fixed meters. His transformation achieved its maximum expression with the publication of the seminal The Branch Will Not Break (1963), which positioned Wright as a curious counterpoint to the Beats and New York schools that predominated on the American coasts.

Wright discovered a terse, imagistic, free verse of clarity and power. During the next 10 years, Wright would go on to pen some of the most beloved and frequently anthologized masterpieces of the century, such as “A Blessing,” “Autumn Begins in Martin’s Ferry, Ohio” and “I Am a Sioux Indian Brave, He Said to Me in Minneapolis.”

Wright was born in Martins Ferry, Ohio, one of many steel-producing towns along the heavily industrialized Upper Ohio River Valley as it borders West Virginia and Pennsylvania. His Midwestern working-class roots held firm through three decades of poetic portraits drawn from heartland realities. Wright thrived on public speaking in grade school and began writing verse in high school. After being drafted into the U.S. Army during World War II, he wrote his mother to forward copies of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ verse and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese. After he was mustered out while serving in occupied Japan, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill and entered the only school that showed interest, Kenyon College.

Wright later attended Yale, from which he graduated cum laude in 1951, after which he received a Fulbright Fellowship and travelled to Rabat, Morocco. After Wright shifted his concentration from vocational education to English and Russian literature, by 1952 he had published in 20 journals and earned the Robert Frost Poetry Prize, election to Phi Beta Kappa and a B.A. degree. He attended the University of Vienna on a Fulbright Fellowship.

In 1954, he went to the University of Washington. In 1957, when his book of poems, The Green Wall (1957), was published, he joined the faculty of the University of Minnesota as an English instructor. In 1959, he earned a Ph.D from the University of Washington with a dissertation on Charles Dickens and his second collection, Saint Judas, was published in the Wesleyan University Press series. During this period, Wright contributed poetry and book reviews to major publications like The Sewanee Review and regularly published in virtually every important journal, from The New Yorker to The New Orleans Poetry Review. Three years later, he won the Ohiona Book Award for Saint Judas (1960).

Wright published The Lion’s Tail and Eyes: Poems Written Out of Laziness and Silence (1962). Other works include: The Branch Will Not Break (1963) and Shall We Gather at the River (1968). Throughout this period, he published regularly in some 15 journals. Wright held subsequent teaching positions at Macalester College, Hunter College and State University of New York. His Collected Poems (1971) won a Pulitzer Prize. He was active for the remainder of the 1970s, when his elegies were issued in Two Citizens (1973), I See the Wind (1974), Old Booksellers and Other Poems (1976), Moments of the Italian Summer (1976) and To a Blossoming Pear Tree (1978).

Wright died from throat cancer on March 25, 1980, shortly after being diagnosed with cancer of the tongue.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Wright_%28poet%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

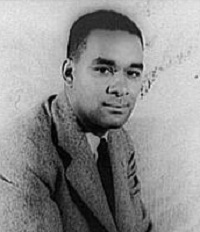

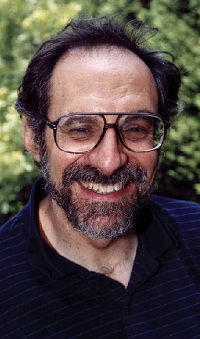

Richard Wright

Richard Wright

1908-1961

Writer and poet Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908, near Natchez, Mississippi. The grandson of slaves and the son of a sharecropper, he went to school in Jackson, Mississippi, only until the ninth grade but had a story published at age 16 while working at various jobs in the South. In 1927, he went to Chicago and worked briefly in the post office but, forced onto relief by the Depression, he joined the Communist Party (1932).

With two more minor works published, he found employment with the Federal Writers Project, and his Uncle Tom’s Children (1938), a collection of four stories, was highly acclaimed. In 1937, he moved to New York City, where he was an editor on the Communist newspaper, Daily Worker, but the publication of Native Son (1940) brought him overnight fame and freedom to write. A stage version (by Wright and Paul Green) followed in 1941 and Wright himself later played the title role in a film version made in Argentina.

Black Boy, published in 1945, is a moving account of his childhood and youth in the South and depicts extreme poverty and his accounts of racial violence against blacks. The autobiography advanced Wright’s reputation but, after living mainly in Mexico (1940-46), he had become so disillusioned with both the Communists and white America that he went off to Paris, where he lived the rest of his life as an expatriate. He continued to write novels, including The Outsider (1953) and The Long Dream (1958), and nonfiction, such as Black Power (1954) and White Man, Listen! (1957), and was regarded by African-American writers, such as James Baldwin, as an inspiration. His naturalistic fiction no longer has the standing it once enjoyed, but his life and works remain exemplary.

Richard Nathaniel Wright died on November 28, 1960 in Paris, France.

Source: http://www.biography.com/people/richard-wright-9537751

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Mary Wroth

Mary Wroth

1587?-1651?

Lady Mary Wroth was the daughter of Robert Sidney, later Earl of Leicester, and the wealthy heiress Barbara Gamage, first cousin to Sir Walter Raleigh. Robert Sidney was himself a poet, the younger brother of Sir Philip Sidney and Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke.

In 1604, Mary was married to Sir Robert Wroth, a wealthy landowner in favor with James I. Although the marriage was not a happy one, Wroth’s favor with the king brought Lady Mary into court circles. She even got a role in Queen Anne’s first masque, Ben Jonson’s Masque of Blackness, as Ethiopian nymph Baryte. She also appeared in Jonson’s Masque of Beauty three years later. Lady Mary became a personal acquaintance of Ben Jonson, who dedicated his The Alchemist to her. Sir Robert Wroth died in 1614 and left Mary in enormous debt.

In 1621, Lady Wroth’s prose romance, The Countess of Montgomeries Urania, was published. Urania caused great controversy because of its purported similarities to actual people and events. In particular, Edward Denny, Baron of Waltham, charged Wroth with slander. He wrote two angry letters to her and attacked the work in a poem. This poem was mocked by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, in the final couplet of her 1664 preface to Sociable Letters. Lady Wroth claimed innocence and wrote a brilliant poem in answer. This did not deter her from writing a sequel, The Second Part of the Countesse of Montgomerys Urania, but the work remained unpublished. She also wrote an unpublished play, Love’s Victory, and some poetry.

Of her later life virtually nothing is known or recorded, the scholarly consensus being that her reputation was permanently besmirched by Urania’s notoriety and that she must have kept a low profile.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/wroth/wrothbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

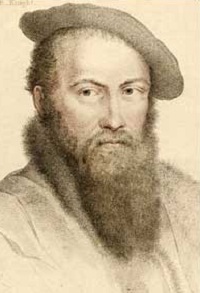

Thomas Wyatt

Thomas Wyatt

1503-1542

Thomas Wyatt was born to Henry and Anne Wyatt at Allington Castle, near Maidstone, Kent, in 1503. Little is known of his childhood education. His first court appearance was in 1516 as Sewer Extraordinary to Henry VIII. In 1516, he also entered St. John’s College, University of Cambridge. Around 1520, when he was only 17 years old, he married Lord Cobham’s daughter, Elizabeth Brooke. She bore him a son, Thomas Wyatt the Younger, in 1521. He became popular at court and carried out several foreign missions for King Henry VIII and also served various offices at home.

He accompanied Sir Thomas Cheney on a diplomatic mission to France in 1526 and Sir John Russell to Venice and the papal court in Rome in 1527. He was made High Marshal of Calais (1528-1530) and Commissioner of the Peace of Essex in 1532. Also in 1532, Wyatt accompanied King Henry and Anne Boleyn, who was by then the King’s mistress, on their visit to Calais. Anne Boleyn married the King in January 1533 and Wyatt served in her coronation in June.

Wyatt was knighted in 1535 but, in 1536, he was imprisoned in the Tower for quarreling with the Duke of Suffolk, and possibly also because he was suspected of being one of Anne Boleyn’s lovers. During this imprisonment, Wyatt witnessed the execution of Anne Boleyn on May 19, 1536, from the Bell Tower, and wrote “V. Innocentia Veritas Viat Fides Circumdederunt me inimici mei.” He was released later that year. Henry, Wyatt’s father, died in November 1536.

Wyatt was returned to favor and made ambassador to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, in Spain. He returned to England in June 1539 and, later that year, was again ambassador to Charles until May 1540. Wyatt’s praise of country life and the cynical comments about foreign courts in his verse epistle, “Mine Own John Poins,” derive from his own experience.

In 1541, Wyatt was charged with treason on a revival of charges originally leveled against him in 1538 by Edmund Bonner, now Bishop of London. Bonner claimed that, while ambassador, Wyatt had been rude about the King’s person and had dealings with Cardinal Pole, a papal legate and Henry’s kinsman, with whom Henry was much angered over Pole’s siding with papal authority in the matter of Henry’s divorce proceedings from Katharine of Aragon. Wyatt was again confined to the Tower, where he wrote an impassioned “Defence.” He received a royal pardon, perhaps at the request of then-queen Catharine Howard, and was fully restored to favor in 1542.

Wyatt was given various royal offices after his pardon but he became ill after welcoming Charles V’s envoy at Falmouth and died at Sherborne on October 11, 1542.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/wyattbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Wycherly

William Wycherly

1641-1715

William Wycherley (c. 1640-December 31, 1715) was an English dramatist of the Restoration period, best known for the plays The Country Wife and The Plain Dealer.

He was born at Clive, Shropshire, near Shrewsbury, where his family was settled on a moderate estate of about £600 a year. After a tour of France, Wycherley returned to England shortly before the restoration of King Charles II and lived at Queen’s College. Wycherley only lived in the provost’s lodgings; he does not seem to have matriculated or taken a degree.

Wycherley left Oxford and took up residence at the Inner Temple but gave little attention to the study of law. Pleasure and the stage were his only interests. His play, Love in a Wood, was produced early in 1671. The Gentleman Dancing Master was published in 1673. It is, however, his two last comedies – The Country Wife (1672) and The Plain Dealer – that sustain Wycherley’s reputation.

Wycherley wrote verses and, when quite an old man, prepared them for the press aided by Alexander Pope, then not much more than a boy. But, notwithstanding all of Pope’s tinkering, they remain contemptible. Pope’s published correspondence with the dramatist was probably edited by him with a view to giving an impression of his own precocity. The friendship between the two cooled, according to Pope’s account, because Wycherley took offence at the numerous corrections on his verses. It seems more likely that Wycherley discovered that Pope, while still professing friendship and admiration, satirized his friend in the “Essay on Criticism.”

Wycherley died on January 1, 1716, and was buried in the vault of the church in Covent Garden.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wycherley

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Elinor Wylie

Elinor Wylie

1885-1928

Elinor Morton Wylie (nee Hoyt, September 7, 1885-December 16, 1928) was an American poet and novelist who was popular before World War II.

Wylie was born in Somerville, New Jersey. Her parents were Henry Martyn Hoyt and Anne Morton McMichael. Her grandfather, Henry M. Hoyt, was a governor of Pennsylvania; she was raised in this socially prominent family in Washington, D.C. Her aunt was Helen Hoyt, a minor poet. In 1912, she graduated from the Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, Maryland. She eloped with Harvard graduate Philip Simmons Hichborn, son of rear-admiral Philip Hichborn; they were married on December 13, 1906. She later eloped with Horace Wylie while still married to Hichborn. She married three times and had a son, Philip Simmons Hichborn Jr., by her first husband. Her last marriage, in 1923, was to William Rose Benet, who was part of her literary circle and brother of Stephen Vincent Benet.

Talented in several arts, she was torn between painting and writing, but her position inside Washington, D.C., literary circles, particularly with John Dos Passos and Edmund Wilson, encouraged her writing efforts. She wrote eight novels and several books of poetry. Her first book, Incidental Numbers (1912), was published privately in England. The first of her books to bring her recognition was her first official collection of poetry, Nets to Catch the Wind (1921). She was named literary editor of Vanity Fair magazine in 1922.

Her other volumes of poetry include: Black Armour (1923); Trivial Breath (1928); Angels and Earthly Creatures (1929); and Collected Poems of Elinor Wylie (1932). Wylie’s literary interests were largely conservative and formal, as demonstrated by her preoccupation with the sonnet. Heavily influenced by 16th and 17th century English poetics, Wylie also shares the Romantics’ infatuation with nature and fantasy.

Her last novel, Orphan Angel (1926), explores what Percy Bysshe Shelley’s life would have been like if he had escaped his early death and moved to America.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elinor_Wylie

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Xenophon

Xenophon

430 BC-354 BC

Xenophon (c. 430-354 BC), also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates. He is known for his writings on the history of his own times, the 4th century BC, preserving the sayings of Socrates, and descriptions of life in ancient Greece and the Persian Empire.

Xenophon’s birth date is uncertain, but most scholars agree that he was born around 430 BC in Athens. He was born into the ranks of the upper classes, thus granting him access to certain privileges of the aristocracy of ancient Attica. While a young man, Xenophon participated in the expedition led by Cyrus the Younger against his older brother, King Artaxerxes II of Persia, in 401 BC. Xenophon’s book, Anabasis (The Expedition or The March Up Country), is his record of the entire expedition against the Persians and the journey home. The Anabasis was used as a field guide by Alexander the Great during the early phases of his expedition into Persia.

Xenophon was later exiled from Athens, most likely because he fought under the Spartan King Agesilaus II against Athens at Coronea. However, there may have been contributory causes, such as his support for Socrates, as well as the fact that he had taken service with the Persians. The Spartans gave him property at Scillus, near Olympia in Elis, where he composed The Anabasis. However, because his son, Gryllus, fought and died for Athens at the Battle of Mantinea while Xenophon was still alive, Xenophon’s banishment may have been revoked.

Xenophon died in either Corinth or Athens. His date of death is uncertain.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xenophon

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

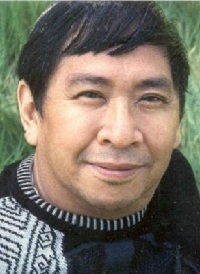

Hisaye Yamamoto

Hisaye Yamamoto

1921-2011

Hisaye Yamamoto (August 23, 1921-January 30, 2011) was a Japanese-American author. She was best known for the short story collection, Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, first published in 1988. Her work confronts issues of the Japanese immigrant experience in America, the disconnect between first- and second-generation immigrants, as well as the difficult role of women in society.

Yamamoto was born to Issei parents in Redondo Beach, California. Her generation, the Nisei, were often in perpetual motion, born into the nomadic existences imposed upon their parents by the California Alien Land Law and the Asian Exclusion Act. As a mainstay, Yamamoto found comfort in reading and writing from a young age, producing almost as much work as she consumed. As a teen, her enthusiasm mounted as Japanese-American newspapers began publishing her letters and short stories.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese navy, an act of war that was both undeclared by the Japanese and unexpected by the United States. Within four months of the bombing, Japanese-Americans numbering close to 120,000 were forced into internment, two-thirds of which were born on American soil. Yamamoto was 20 years old when her family was placed in the internment camp in Poston, Arizona. In an effort to stay active, Yamamoto began reporting for The Poston Chronicle, the camp newspaper. She started by publishing her first work of fiction, “Death Rides the Rails to Poston,” a mystery that was later added to Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories, followed shortly thereafter by a much shorter piece, “Surely I Must be Dreaming.” The three years that Yamamoto spent at Poston profoundly impacted all of her subsequent writing.