Author Biographies 24

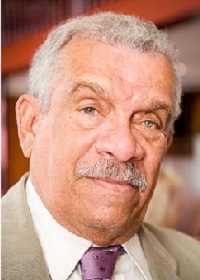

Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott

1930-2017

Derek Alton Walcott (born January 23, 1930-March 17, 2017) was a Saint Lucian poet, playwright, writer and visual artist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992 and the T.S. Eliot Prize in 2011 for White Egrets. His works include the Homeric epic, Omeros. Robert Graves wrote that Walcott “handles English with a closer understanding of its inner magic than most, if not any, of his contemporaries.”

Walcott was born and raised in Castries, Saint Lucia, in the West Indies, with a twin brother, the future playwright Roderick Walcott, and a sister. His mother, a teacher, had a love of the arts and would often recite poetry. His father, who painted and wrote poetry, died at 31 from mastoiditis.

Walcott studied as a writer, becoming “an elated, exuberant poet madly in love with English” and strongly influenced by Modernist poets such as T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

At 14, Walcott published his first poem in The Voice of St. Lucia, a Miltonic, religious poem. By 19, Walcott had self-published his two first collections, 25 Poems (1948) and Epitaph for the Young: XII Cantos (1949), which he distributed himself.

With a scholarship, he studied at the University of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica, then moved to Trinidad in 1953, becoming a critic, teacher and journalist. Exploring the Caribbean and its history in a colonialist and post-colonialist context, his collection, In a Green Night: Poems 1948-1960 (1962), saw him gain an international public profile.

He founded the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre at Boston University in 1981. Walcott taught literature and writing at Boston University, retiring in 2007. His later collections include Tiepolo’s Hound (2000), The Prodigal (2004) and White Egrets (2010), which was the recipient of the T.S. Eliot Prize.

Walcott was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992, the first Caribbean writer to receive the honor. In 2009, he began a three-year distinguished scholar-in-residence position at the University of Alberta. In 2010, he became Professor of Poetry at the University of Essex.

Walcott died at his home in Cap Estate, St. Lucia, on March 17, 2017. He was 87.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derek_Walcott

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Alice Walker

Alice Walker

1944-

Alice Malsenior Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American author, poet and activist. She has written both fiction and essays about race and gender.

Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, the youngest of eight children, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Lou Tallulah Grant. Her father, who was, in her words, “wonderful at math but a terrible farmer,” earned only $300 a year from sharecropping and dairy farming. Her mother supplemented the family income by working as a maid. She worked 11 hours a day for $17 per week to help pay for Alice to attend college.

After high school, Walker went to Spelman College in Atlanta on a full scholarship in 1961 and later transferred to Sarah Lawrence College near New York City, graduating in 1965.

Walker’s first book of poetry was written while she was a senior at Sarah Lawrence. She took a brief sabbatical from writing while working in Mississippi in the civil rights movement. Walker resumed her writing career when she joined Ms. Magazine as an editor before moving to northern California in the late 1970s. Her 1975 article, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” published in Ms. Magazine, helped revive interest in the work of Hurston, who inspired Walker’s writing and subject matter. In 1973, Walker and fellow Hurston scholar Charlotte D. Hunt discovered Hurston’s unmarked grave in Ft. Pierce, Florida. The women collaborated to buy a modest headstone for the gravesite.

In addition to her collected short stories and poetry, Walker’s first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, was published in 1970. In 1976, Walker’s second novel, Meridian, was published. In 1982, Walker published what has become her best-known work, the novel, The Color Purple.

Walker has written several other novels, including The Temple of My Familiar and Possessing the Secret of Joy. She has published a number of collections of short stories, poetry and other works.

Her short stories include the 1973 “Everyday Use,” in which she discusses feminism, racism and the issues raised by young black people who leave home and lose respect for their parents’ culture.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Walker

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

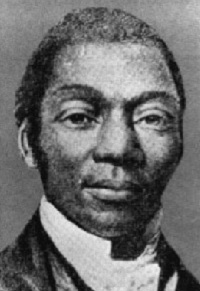

David Walker

David Walker

1785-1830

David Walker was an abolitionist, orator and author of David Walker’s Appeal. Although Walker’s father, who died before his birth, was enslaved, his mother was a free woman; thus, when he was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, in September 1785, he was also free, following the “condition” of his mother as prescribed by Southern laws regulating slavery.

Relocating to Boston in the mid-1820s, he became a clothing retailer and, in 1828, married a woman named Eliza. They had one son, Edward (or Edwin) Garrison Walker, born after Walker’s death in 1830.

An active figure in Boston’s African-American community during the late 1820s, David Walker had a reputation as a generous, benevolent person who sheltered fugitives and frequently shared his income with the poor. He joined the Methodist Church and in 1827 became a general agent for Freedom’s Journal, a newly established African-American newspaper. During the two years of the newspaper’s existence, he regularly supported the New York City-based publication, finding subscribers, distributing copies and contributing articles. He was also a notable member of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, an antislavery and civil rights organization founded in 1826. In lectures before the association, Walker spoke out against slavery and colonization, while urging African-American solidarity.

In September 1829, he published David Walker’s Appeal. In this pamphlet, he fiercely denounced slavery, colonization and the institutional exclusion, oppression and degradation of African peoples. His Appeal was a militant call for united action against the sources of the “wretchedness” of African-Americans, enslaved and free. Often reprinted, widely circulated and highly regarded by a number of African-American readers, Walker’s Appeal generated a vehement response from white Americans, especially in the South. Several Southern state legislatures passed laws banning such “seditious” literature and reinforced legislation forbidding the education of slaves in reading and writing. The governors of Georgia and Virginia and the mayor of Savannah wrote letters to the mayor of Boston expressing outrage about the Appeal and demanding that Walker be arrested and punished. In Georgia, a bounty was offered on him, $10,000 alive, $1,000 dead. In the North, newspapers attacked the pamphlet, as did white abolitionists (and pacifists) Benjamin Lundy and William Lloyd Garrison, who admired Walker’s courage and intelligence but condemned the circulation of the Appeal as imprudent.

Walker died in the summer of 1830. Although the cause and circumstances of his death are mysterious, many have suspected that he was poisoned.

Source: http://www.answers.com/topic/david-walker

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

George Walker

George Walker

1772-1847

George Walker (December 24, 1772-February 8, 1847) was an English Gothic novelist. He was born in Falcon Square, Cripplegate, London, England. He worked as a bookseller and music publisher. His writings were anti-reform, reacting to writers such as William Godwin and Thomas Holcroft.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Walker_%28novelist%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Margaret Walker

Margaret Walker

1915-1998

Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander (July 7, 1915-November 30, 1998) was an African-American poet and writer. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, she wrote as Margaret Walker. One of her best-known poems is “For My People.”

Walker was born to Sigismund C. Walker, a Methodist minister and Marion Dozier Walker, who helped their daughter by teaching her philosophy and poetry as a child. Her family moved to New Orleans when Walker was a young girl. She attended school there, including several years of college before she moved north

In 1935, Margaret Walker received her Bachelor of Arts degree from Northwestern University and, in 1936, she began work with the Federal Writers’ Project under the Works Progress Administration. In 1942, she received her master’s degree in creative writing from the University of Iowa. In 1965, she returned to that school to earn her Ph.D.

Walker married Firnist Alexander in 1943; they had four children and lived in Mississippi. Walker was a literature professor at what is today Jackson State University (1949 to 1979). In 1968, Walker founded the Institute for the Study of History, Life and Culture of Black People (now the Margaret Walker Alexander National Research Center) at the school. She went on to serve as the Institute’s director.

Among Walker’s more popular works are her poem, “For My People,” which won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition in 1942 under the judgeship of editor Stephen Vincent Benet, and her 1966 novel, Jubilee, which also received critical acclaim. The book was based on her own great-grandmother’s life as a slave.

In 1975, Walker released three albums of poetry on Folkways Records: Margaret Walker Alexander Reads Langston Hughes, P.L. Dunbar and J.W. Johnson; Margaret Walker Reads Margaret Walker and Langston Hughes; and The Poetry of Margaret Walker. In 1988, she sued Alex Haley, claiming his novel, Roots: The Saga of an American Family, had violated Jubilee’s copyright. The case was dismissed.

Walker died of breast cancer in Chicago, Illinois, in 1998

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Walker

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

David Foster Wallace

David Foster Wallace

1962-2008

David Foster Wallace (February 21, 1962-September 12, 2008) was an American author of novels, essays and short stories and a professor at Pomona College in Claremont, California. He was widely known for his 1996 novel, Infinite Jest, which Time included in its All-Time 100 Greatest Novels list (covering the period 1923-2006).

Wallace was born in Ithaca, New York, to James Donald Wallace and Sally Foster Wallace. In his early childhood, Wallace lived in Champaign, Illinois. When he was in fourth grade, the family moved to Urbana and he attended Yankee Ridge school. He attended his father’s alma mater, Amherst College, and majored in English and philosophy, with a focus on modal logic and mathematics. In 1987, he received a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from the University of Arizona.

Wallace committed suicide by hanging himself on September 12, 2008, as confirmed by the October 27, 2008, autopsy report.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Foster_Wallace

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Edgar Wallace

Edgar Wallace

1875-1932

Edgar Wallace was a British novelist, playwright and journalist who produced popular detective and suspense stories and was in his time “the king” of the modern thriller. Wallace’s literary output – 175 books, 24 plays and countless articles and review sketches – have undermined his reputation as a fresh and original writer.

Wallace was born in Greenwich in the same year as Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1875. He was brought up as an adopted child in the family of Dick Freeman, a London fish porter. His parents were actors, Polly Richards and Richard Horatio Edgar Marriott, who used the false name of Walter Wallace on the birth records. Young Wallace left school at the age of 12 and took menial jobs before enlisting at the age of 18 in the Army, serving in the Royal West Kent Regiment from 1893 to 1896.

In 1896, Wallace was sent to South Africa, where he was in the Medical Staff Corps. During this period, he met the Reverend William Shaw Caldecott and Mrs. Marion Caldecott, who was a writer and willing to help Wallace in his writing aspirations. Wallace began to contribute to various journals and wrote war poems, later collected in The Mission That Failed (1898) and other volumes.

After his discharge in 1899, Wallace became a correspondent for Reuters and The London Daily Mail. His reports about Horatio Herbert Kitchnerer infuriated the influential British field marshal and Wallace was banned as a war correspondent until World War I. He served in 1902 as the editor of The Rand Daily Mail in Johannesburg before returning to London. During the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05), Wallace was sent by The Daily Mail to Vigo to examine a conflict in which the Russians opened fire on a British fishing fleet in the belief that it was the Japanese Navy. During this period, he learned about the activities of Russian and English spies operating around the coasts of Spain and Portugal. Later, Wallace returned to the world of secret agents in his stories, although he mostly concentrated on crime and detective books. His most famous spy story, “Code No. 2,” first appeared in The Stand Magazine of April 1916 and later in various collections and anthologies.

Wallace’s first novel, The Four Just Men, appeared in 1905 and was published by his own Tallis Press. It was not until the publication of Sanders of the River (1911) that his fame as a writer was established. Wallace then wrote several additional stories using his African experiences as background.

Wallace worked in the 1900s and 1910s in several journals, among them The Daily Mail (1903-1907), Standard (1910), The Week-End Racing Supplement (1910-12), Evening News (1910-1912), The Story Journal (1913) and Town Topics (1913-16). He was later a racing columnist for The Star (1927-32) and The Daily Mail (1930-32).

Wallace wrote his works at a prodigious pace: One of his most popular plays, On the Spot (1931), was finished in four days. His autobiography, People; Edgar Wallace: The Biography of a Phenomenon, appeared in 1926.

Wallace enjoyed an extremely good income from his writings, but he lost fortunes because of his extravagant lifestyle and obsessive betting on the wrong horses. Toward the end of his life, Wallace estimated that his work as a playwright was more important than his work as a writer of stories. It was largely the success of the plays – The Calendar (1929), On the Spot and The Case of The Frightened Lady (1931) – that led to his being invited to Hollywood to work as a scriptwriter.

Wallace died on February 10, 1932, en route to Hollywood to work on the screenplay for King Kong.

Source: http://www.classicreader.com/author/101/about/

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Edmund Waller

Edmund Waller

1606-1687

Edmund Waller was born March 3, 1606, in Coleshill, Hertfordshire (now in Buckinghamshire), the eldest son of a wealthy landowner. He was educated at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge. He was elected to Parliament at the young age of 16 and became a noted orator.

Waller was a celebrated poet and wit in his lifetime and many of his poems had long circulated in manuscript before the 1645 publication of his Poems. The first fully authorized edition was in 1664. In 1655 appeared the “Panegyrick to my Lord Protector,” celebrating Cromwell and, in 1660, “To the King, upon His Majesty’s Happy Return,” celebrating the restoration of King Charles II. Waller’s later works include Divine Poems (1685) and The Second Part of Mr. Waller’s Poems, posthumously published in 1690.

During the troubled 1640s, Waller tried to maintain a moderate course between the king and his opponents. In 1643, he devised a plot to oust the Parliamentary rebels, “Roundheads,” and to secure London for the king. When the plot, known as “Waller’s Plot,” was discovered in May, Waller was arrested and brought before the Parliament. Waller confessed and pleaded for mercy, but his freedom lay in bribes and betrayal of his co-conspirators – Waller was fined heavily (£10,000) and exiled.

He lived in Paris, traveling occasionally in Italy and Switzerland, until 1652, when he was allowed to return. He returned to Parliament and was restored to royal favor at the Restoration.

Waller died in his bed, aged 82, on October 21, 1687.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/waller/wallerbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Jeannette Walls

Jeannette Walls

1960-

Jeannette Walls is a writer and journalist widely known as former gossip columnist for MSNBC.com and as author of The Glass Castle, a memoir of the nomadic family life of her childhood.

Walls was born on April 21, 1960, in Phoenix, Arizona, to Rex Walls, an electrician, and Rose Mary Walls, an artist. The family shuttled from Phoenix to California (including a brief stay in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco), Battle Mountain, Nevada, and Welch, West Virginia, with periods of homelessness. Walls moved to New York at age 17 and graduated in 1984 with honors from Barnard College.

Walls has written for New York Magazine (The Intelligencer column, 1987-1993), Esquire (1993-1998) and USA Today. Early in her career, she interned at a local Brooklyn newspaper called The Phoenix and eventually became a full-time reporter there, although the newspaper went out of business in 1998. She contributed regularly to the gossip column, Scoop, at MSNBC.com from 1998 until her departure to write full-time in 2007.

In 2000, Walls published the book, Dish: The Inside Story on the World of Gossip. In 2005, Walls published the bestselling memoir, The Glass Castle. In 2009, she published her first fiction book, Half Broke Horses: A True-Life Novel, based on the life of her grandmother, Lily Casey Smith.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeannette_Walls

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Eric Walrond

Eric Walrond

1898-1966

Eric Derwent Walrond (December 18, 1898-August 8, 1966) was an African-American Harlem Renaissance writer who made a lasting contribution to literature; his work still being in print today as a classic of its era. He was well-travelled, being born in Georgetown, Guyana (British Guiana) the son of a Barbadian mother and a Guyanese father, moving early in life to live in Barbados and then Panama, New York and, eventually, England.

Walrond’s most famous book was Tropic Death, published in New York City in 1926 when he was 28, in which he brought together 10 stories, at least one of which had been previously published in small magazines. He had published other short stories prior to this, as well as a number of essays.

Much of the dialogue between Walrond’s characters is written in dialect, using the many different tongues loosely centered on the English language to portray the diversity of characters associated with the Pan-Caribbean diaspora.

When he was eight, his father left and Walrond moved with his mother, Ruth, to live with relatives in Barbados, where he attended St. Stephen’s Boys’ School, before moving to Panama at the time when the Panama Canal was being constructed. Here, Walrond completed his school education and became fluent in Spanish as well as English. Following training as a secretary and stenographer, he was employed as a clerk in the Health Department of the Canal Commission at Cristobal and as a reporter for The Panama Star-Herald newspaper. In 1918, he moved to New York, where he attended Columbia University, being tutored by Dorothy Scarborough.

In New York, Walrond worked at first as hospital secretary, porter and stenographer. His utopian sketch of a united Africa, “A Senator’s Memoirs” (1921), won a prize sponsored by Marcus Garvey and, after working briefly for Garvey, he became a protege of the National Urban League’s director, Charles S. Johnson. Here he was a contributor to, and business manager of, the Urban League’s Opportunity magazine between 1925-27, which had been founded in 1923 to help bring to prominence African-American contributors to the arts and politics of the 1920s. He was also a contributor to Smart Set, Vanity Fair and Negro World.

His short stories included: “On Being Black” (1922); “On Being a Domestic” (1923); “Miss Kenny’s Marriage” (1923); “The Stone Rebounds” (1923); “Vignettes of the Dusk” (1924); “The Black City” (1924); and “City Love” (1927). In 1928-29, Walrond was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship for Fiction.

After a decade in America, Walford left for England, where he met English writers and artists during the 1930s, including Winifred Holtby. In later life, he continued to employ his editorial skills from time to time while working as an accountant.

At the age of 67, he collapsed on a street in central London and was pronounced dead on arrival at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_D._Walrond

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Minette Walters

Minette Walters

1949-

Minette Walters (born September 26, 1949) is an English crime writer.

After her birth in Bishop’s Stortford to a serving army officer, Capt. Samuel Jebb (Royal Signals), and his wife Colleen, the first 10 years of Walters’ life were spent moving between army bases in the north and south of England. Following the death of her father from kidney failure in 1960, she spent a year at the Abbey School in Reading, Berkshire, before being granted a free Foundation Scholarship at the Godolphin boarding school in Salisbury. She graduated from Trevelyan College, Durham, in 1971 with a B.A. in French.

Walters joined IPC Magazines as a sub-editor in 1972 and became an editor of Woman’s Weekly Library the following year. She supplemented her salary by writing romantic novelettes, short stories and serials in her spare time. She turned freelance in 1977 but continued to write for magazines to cover her bills.

Her first full-length novel, The Ice House, was published in 1992, followed by The Sculptress and The Scold’s Bridle.

As part of the British project “Quick Reads,” a program to encourage literacy among adults with reading difficulties, Walters wrote a 20,000-word novella, Chickenfeed. In September 2007, Walters released her 14th book, The Chameleon’s Shadow.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minette_Walters

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

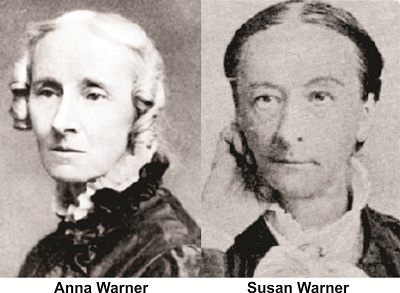

Susan and Anna Warner

Susan and Anna Warner

1827-1915/1819-1885

Anna Bartlett Warner (August 31, 1827-January 22, 1915) was an American writer and author of several hymns and religious songs for children. She was born on Long Island and died in Highland Falls, New York. Susan Bogert Warner (July 11, 1819-March 17, 1885) was an American evangelical writer of religious fiction, children’s fiction and theological works.

The Warners could trace their lineage back to the Puritan Pilgrims on both sides. Their father was Henry Warner, a New York City lawyer originally from New England, and their mother was Anna Bartlett, from a wealthy, fashionable family in New York’s Hudson Square. When they were young children, their mother died and their father’s sister, Fanny, came to live with them. Although Henry Warner had been a successful lawyer, he lost most of his fortune in the Panic of 1837 and in subsequent lawsuits and poor investments. The family had to leave their mansion at St. Mark’s Place in New York and move to an old Revolutionary War-era farmhouse on Constitution Island, near West Point, New York. In 1849, seeing little change in their family’s financial situation, Susan and Anna started writing to earn money.

Born in New York City, Susan wrote, under the name of “Elizabeth Wetherell,” 30 novels, many of which went into multiple editions. However, her first novel, The Wide, Wide World (1850), was the most popular. Other than Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it was perhaps the most widely circulated story of American authorship. Other works include: Queechy (1852); The Law and the Testimony (1853); The Hills of the Shatemuc (1856); The Old Helmet (1863); and Melbourne House (1864). In the 19th century, critics admired the depictions of rural American life in her early novels. American reviewers also praised Warner’s Christian and moral teachings, while London reviewers tended not to favor her didacticism.

Some of Susan Warner’s works were written jointly with her younger sister, Anna Bartlett Warner, who sometimes wrote under the pseudonym “Amy Lothrop.” The Warner sisters also wrote famous children’s Christian songs. Susan wrote “Jesus Bids Us Shine,” while Anna was author of the first verse of the well-known children’s song, “Jesus Loves Me, This I Know,” which she wrote at Susan’s request.

Both sisters became devout Christians in the late 1830s. After their conversion, they became confirmed members of the Mercer Street Presbyterian church although, in later life, Susan Warner was drawn into Methodist circles. The sisters also conducted Bible studies for the West Point cadets. When they were on military duty, the cadets would sing “Jesus Loves Me.” The popularity of the song was so great that, upon Anna Warner’s death, she was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. She was the first civilian to be given this honor.

Susan Warner died in Highland Falls, New York.

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susan_Warner

and

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Bartlett_Warner

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy Otis Warren

1728-1814

Mercy Otis Warren (September 14, 1728-October 19, 1814) was an American writer and playwright. She was known as the “Conscience of the American Revolution.” Otis was America’s first female playwright, having written unbylined, anti-British and anti-Loyalist propaganda plays from 1772 to 1775, and was the first woman to create a Jeffersonian (anti-Federalist) interpretation of the Revolution, entitled History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, published in three volumes in 1805.

Otis was the third child of 13 born to Colonel James Otis and Mary Allyne Otis in Barnstable, Massachusetts. Although she had no formal education, she studied with the Reverend Jonathan Russell while he tutored her brothers in preparation for college.

In 1754, Otis married James Warren, a prosperous merchant and farmer from Plymouth, Massachusetts. They settled in Plymouth and had five sons. Her husband had a very distinguished political career. In 1765, he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, eventually becoming speaker of the House and president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. He also served for a time as paymaster to George Washington’s army during the Revolutionary War. Mercy Warren actively participated in the political life of her husband, who encouraged her to write, fondly referring to her as the “scribbler,” and she became his chief correspondent and sounding board.

She became a correspondent and adviser to many political leaders, including Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and especially John Adams, who became her literary mentor in the years leading to the Revolution. Because Warren knew most of the leaders of the Revolution personally, she was continually at or near the center of events from 1765 to 1789. She combined her vantage point with a talent for writing to become both a poet and a historian of the Revolutionary era.

All of her work was published anonymously until 1790. She wrote several plays, including the satiric The Adulateur (1772). Directed against Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts, the play foretold the War of Revolution. In 1773, she wrote The Defeat, also featuring the character based on Hutchinson and, in 1775, Warren published The Group, a satire conjecturing what would happen if the British king abrogated the Massachusetts charter of rights. The anonymously published The Blockheads (1776) and The Motley Assembly (1779) are also attributed to her. In 1788, she published Observations on the New Constitution, whose ratification she opposed as an Anti-Federalist.

In 1790, she published Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous, the first work bearing her name. The book contains 18 political poems and two plays. In 1805, she completed her literary career with a three-volume History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution.

Mercy Otis Warren died in October 1814, at the age of 86.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercy_Otis_Warren

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren

1905-1989

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905-September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist and literary critic and was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He founded the influential literary journal, The Southern Review, with Cleanth Brooks in 1935. He received the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for the Novel for his novel, All the King’s Men (1946), and the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1958 and 1979. He is the only person to have won Pulitzer Prizes for both fiction and poetry.

Warren was born in Guthrie, Kentucky, which is very near the Tennessee-Kentucky border, to Robert Warren and Anna Penn. Warren’s mother’s family had roots in Virginia, having given their name to the community of Penn’s Store in Patrick County, Virginia. Warren graduated from Clarksville High School in Clarksville, Tennessee, Vanderbilt University in 1925 and the University of California, Berkeley, in 1926. Warren later attended Yale University and obtained his B. Litt. as a Rhodes Scholar from New College, Oxford, England, in 1930. He also received a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in Italy during the rule of Benito Mussolini. That same year, he began his teaching career at Southwestern College (now Rhodes College) in Memphis, Tennessee.

While still an undergraduate at Vanderbilt, Warren became associated with the group of poets there known as “The Fugitives” and, somewhat later, during the early 1930s, Warren and some of the same writers formed a group known as the Southern Agrarians. He contributed “The Briar Patch” to the Agrarian manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand, along with 11 other Southern writers and poets. In 1956, Warren published a small book, titled Segregation: The Inner Conflict in the South. In 1965, he published Who Speaks for the Negro?, a collection of interviews with black civil rights leaders, including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., thus further distinguishing his political leanings from the more conservative philosophies associated with fellow Agrarians.

Warren served as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, Poet Laureate, 1944-1945, and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1947 for his best-known work, the novel, All the King’s Men. Warren won Pulitzer Prizes in poetry in 1958 for Promises: Poems 1954-1956 and, in 1979, for Now and Then.

He lived the latter part of his life in Fairfield, Connecticut, and Stratton, Vermont, where he died of complications from bone cancer. He is buried at Stratton, Vermont.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Penn_Warren

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington

1856-1915

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856-November 14, 1915) was an American political leader, educator, orator and author. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915. Representing the last generation of black leaders born in slavery, and speaking for those blacks who had remained in the New South in an uneasy modus vivendi with the white Southerners, Washington was able throughout the final 25 years of his life to maintain his standing as the black leader because of the sponsorship of powerful whites, substantial support within the black community, his ability to raise educational funds from both groups and his skillful accommodation to the social realities of the age of segregation.

Washington was born into slavery to a white father and a slave mother in a rural area in southwestern Virginia. After emancipation, he worked in West Virginia in a variety of manual labor jobs before making his way to Hampton Roads seeking an education. He worked his way through Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) and attended college at Wayland Seminary. After returning to Hampton as a teacher, in 1881 he was named as the first leader of the new Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Washington received national prominence for his “Atlanta Address of 1895,” attracting the attention of politicians and the public as a popular spokesperson for African-American citizens. Washington built a nationwide network of supporters in many black communities, with black ministers, educators and businessmen composing his core supporters. Washington played a dominant role in black politics, winning wide support in the black community and among more liberal whites (especially rich Northern whites). He gained access to top national leaders in politics, philanthropy and education. Washington’s efforts included cooperating with white people and enlisting the support of wealthy philanthropists, which helped raise funds to establish and operate thousands of small community schools and institutions of higher education for the betterment of blacks throughout the South, work that continued for many years after his death.

Northern critics called Washington’s followers the “Tuskegee Machine.” After 1909, Washington was criticized by the leaders of the new NAACP, especially W.E.B. DuBois, who demanded a harder line on civil rights protests. Washington replied that confrontation would lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks, and that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way to overcome pervasive racism in the long run. Some of his civil rights work was secret, such as funding court cases.

In addition to the substantial contributions in the field of education, Washington was the author of 14 books; his autobiography, Up from Slavery, first published in 1901, is still widely read today. During a difficult period of transition for the United States, he did much to improve the overall friendship and working relationship between the races. His work greatly helped lay the foundation for the increased access of blacks to higher education, financial power, and understanding of the U.S. legal system led to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and adoption of important federal civil rights laws.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Booker_T._Washington

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

George Washington

George Washington

1732-1799

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732. He lost his father at age 11 and his half brother, Lawrence, took over the paternal role. Washington’s mother was protective and demanding, keeping him from joining the British navy as Lawrence wanted. Lawrence owned Mount Vernon and George lived with him from the age of 16. He was schooled entirely in Colonial Virginia and never went to college. He was good at math, which suited his chosen profession of surveying.

In 1749, Washington was appointed as surveyor for Culpeper County, Virginia, after a trek for Lord Fairfax into the Blue Ridge Mountains. He was in the military from 1752-58 before being elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1759. He spoke against Britain’s policies and became a leader in the Association. From 1774-75, he attended both Continental Congresses. He led the Continental Army from 1775-1783 during the American Revolution. He then became the president of the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

Washington joined the Virginia militia in 1752. He created and then was forced to surrender Fort Necessity to the French. He resigned from the military in 1754 and rejoined in 1766 as an aide-de-camp to General Edward Braddock. When Braddock was killed during the French and Indian War (1754-63), he managed to stay calm and keep the unit together as they retreated.

Washington was unanimously named Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. This army was no match for the British regulars and Hessians. He led them to significant victories, such as the capture of Boston, along with major defeats including the loss of New York City. After the winter at Valley Forge (1777), the French recognized American Independence. Baron von Steuben arrived and began training his troops. This help led to increased victories and the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781.

Despite being a member of the Federalist Party, Washington was immensely popular as a war hero and was an obvious choice as the first president for both federalists and anti-federalists. He was unanimously elected by the 69 electors. His runner up, John Adams, was named vice president. Washington was able to rise above the politics of the day and carry every electoral vote – 132 from 15 states – to win a second term. John Adams remained the vice president.

Washington did not run a third time. He retired to Mount Vernon. He was again asked to be the American commander if the U.S. went to war with France over the XYZ affair. However, fighting never occurred on land and he did not have to serve. He died on December 14, 1799, possibly from a streptococcal infection of his throat made worse from being bled four times.

Source: http://americanhistory.about.com/od/georgewashington/p/pwashington.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Wendy Wasserstein

Wendy Wasserstein

1950-2006

Wendy Wasserstein (October 18, 1950-January 30, 2006) was an American playwright and an Andrew Dickson White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University.

Wasserstein was born in the Brooklyn section of New York City to Morris Wasserstein, a wealthy textile executive, and his wife, Lola (nee Liska) Schleifer, an amateur dancer who moved to the United States from Poland when her father was accused of being a spy.

A graduate of the Calhoun School, Wasserstein earned a B.A. in history from Mount Holyoke College in 1971, an M.A. in creative writing from City College of New York, and an M.F.A. in 1976 from the Yale School of Drama. In 1990, she received an honoris causa Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Mount Holyoke College and, in 2002, she received an honoris causa Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Bates College.

Wasserstein’s first production of note was the play, Uncommon Women and Others. In 1989, she won the Tony Award, the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play, The Heidi Chronicles. Her other plays include: The Sisters Rosensweig; Isn’t It Romantic; An American Daughter; Old Money; and Third, which opened in 2005.

During her career, which spanned nearly four decades, Wasserstein wrote 11 plays, winning a Tony Award, a Pulitzer Prize, a New York Drama Critics Circle Award, a Drama Desk Award and an Outer Critics Circle Award. In addition, she wrote the screenplay for the 1998 film, The Object of My Affection.

Wasserstein was hospitalized with lymphoma in December 2005 and died on January 30, 2006, aged 55.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wendy_Wasserstein

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Yoko Kawashima Watkins

Yoko Kawashima Watkins

1933-2021

Yoko Kawashima Watkins was born in Japan in 1933. Her family lived in Manchuria, a region in northern China, where her father was stationed as a Japanese government official. This region of China had been under Japanese control since 1931. The family later moved to Nanam in northern Korea, where her father was overseeing Japanese political interests. Japan had taken control of Korea in 1910.

Although the family lived in Korea, they followed many Japanese traditions. Yoko, her brother, Hideyo, and her sister, Ko, practiced calligraphy, the art of serving and receiving tea and classic Japanese dance. Yoko’s family lived very comfortably in Korea until July of 1945, when it became clear that Japan was losing World War II. Yoko, her sister and her mother had to flee Korea to ensure their safety. Because Japan’s presence in Korea was greatly resented there, the family fled back to Japan.

Yoko survived the journey back to Japan, where she finished her secondary schooling. She then attended Kyoto University, where she was in an English-language program. She graduated and worked at the U.S. Air Force Base as a translator, where she met her future husband. She married Donald Watkins, an American pilot, in 1953. In 1955, her husband was transferred to the U.S., where they lived in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Oregon and finally settled in Brewster, Massachusetts. Together the couple had four children.

In 1976, Watkins began writing So Far from the Bamboo Grove. It was published in 1986 and won many awards. In 1994, she published a second book, My Brother, My Sister and I. In addition to writing, she gave lectures, visited schools, answered questions and gave advice to students.

Watkins died at her home in Brewster on December 8, 2021.

Source: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/102355.Yoko_Kawashima_Watkins

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Larry Watson

Larry Watson

1947-

Larry Watson is an American author of novels, poetry and short stories. He was born in 1947 in Rugby, North Dakota. He grew up in Bismarck, North Dakota. He earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts at the University of North Dakota. He subsequently earned a doctorate in creative writing from the University of Utah.

He taught English at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point for 25 years.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_Watson_(writer)

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

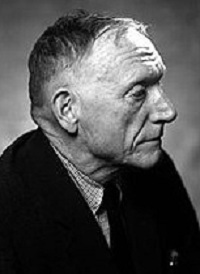

Evelyn Waugh

Evelyn Waugh

1903-1966

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (October 28, 1903-April 10, 1966), known as Evelyn Waugh, was an English writer of novels, travel books and biographies. He was also a prolific journalist and reviewer. His best-known works include his early satires, Decline and Fall (1928) and A Handful of Dust (1934), his novel, Brideshead Revisited (1945), and his trilogy of World War II novels, collectively known as Sword of Honour (1952-61).

The son of a publisher, Waugh was educated at Lancing and Hertford College, Oxford, and worked briefly as a schoolmaster before becoming a full-time writer. As a young man, he acquired many fashionable and aristocratic friends and developed a taste for country house society that never left him. In the 1930s, he traveled extensively, often as a special newspaper correspondent; he was reporting from Abyssinia at the time of the 1935 Italian invasion. He served in the British armed forces throughout the World War II, first in the Royal Marines and later in the Royal Horse Guards. All these experiences, and the wide range of people he encountered, were used in Waugh’s fiction, generally to humorous effect; even his own mental breakdown in the early 1950s, brought about by misuse of drugs, was fictionalized.

Waugh had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1930, after the failure of his first marriage. His traditionalist stance led him to oppose strongly all attempts to reform the Church; the changes brought about in the wake of the Second Vatican Council of 1962-65, particularly the introduction of the vernacular Mass, greatly disturbed him. This blow, together with a growing dislike for the welfare state culture of the post-war world and a decline in his health, saddened his final years, although he continued to write. To the public at large he generally displayed a mask of indifference, but he was capable of great kindness to those he considered his friends, many of whom remained devoted to him throughout his life. After his death in 1966, he acquired a new following through film and television versions of his work, such as Brideshead Revisited in 1982.

On Easter Day, April 10, 1966, after attending a Latin Mass in a neighboring village with members of his family, Waugh died suddenly of heart failure at his Combe Florey home.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evelyn_Waugh

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Frank J. Webb

Frank J. Webb

1828-1894

Frank J. Webb was an African-American novelist, poet and essayist. His only published novel, The Garies and Their Friends (1857), was the second novel to be published by an African-American.

Born in Philadelphia on March 21, 1828, Webb was an active part of the city’s community of free African-Americans by the time he married in 1845. His wife, Mary, gained renown for her dramatic readings of works by Shakespeare, Sheridan and Longfellow, attracting the attention of Harriet Beecher Stowe and other prominent literary abolitionists. Stowe was so impressed by Mary’s readings that she adapted scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin expressly for her performance and helped to arrange a transatlantic tour. With letters of introduction from Stowe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the Webbs traveled to England in 1856, where Mary’s dramatic readings garnered further acclaim. The couple received a warm welcome from many British nobles, including Lady Noel Byron, to whom he dedicated The Garies and Their Friends, and Henry, Lord Brougham, who wrote an enthusiastic introduction. The London firm of G. Routledge and Company published the novel in 1857, with an additional preface by Stowe.

Although The Garies and Their Friends received favorable reviews in England, it went relatively unnoticed in the United States until it was reprinted in 1969. It has less to do with slavery than with the lives of free African-Americans in the North and the violent racism that they face there. Its critique of Northern white racism, including its satirical portraits of several “benevolent-minded” but patronizing white Philadelphians, may have made it unpalatable to the readers who had made sentimental abolitionist works like Uncle Tom’s Cabin bestsellers. Moreover, its frank and sympathetic portrayal of a mixed-race marriage would likely have offended even the most progressive readers on both sides of the color line. Critical perspectives on the novel since its 1969 republication have been mixed. While Webb is often faulted for his sentimentalism and his apparent embrace of white middle-class values, he has also been credited for his realistic portrayal of the tense relations between whites and blacks in one of the most racially integrated cities in America at mid-century.

Soon after the novel’s publication, the Webbs relocated to Jamaica, hoping the warmer climate would benefit Mary’s poor health. After Mary’s death in 1859, Webb stayed in Jamaica for 10 more years, remarrying and fathering four children before returning to the U.S. in 1869. In Washington, he worked as a clerk for the Freedmen’s Bureau and wrote several essays, poems and two novellas for the African-American journal, The New Era. Little is known about his later years, but research by Allan Austin and Eric Gardner has revealed that he moved to Galveston, Texas, in 1870, and died there in 1894.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_J._Webb

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Mary Webb

Mary Webb

1881-1927

Mary Webb (March 25, 1881-October 8, 1927) was an English Romantic novelist and poet of the early 20th century whose work is set chiefly in the Shropshire countryside and among Shropshire characters and people she knew. Her novels have been successfully dramatized.

She was born Gladys Mary Meredith in the Shropshire village of Leighton, eight miles (13 km) southeast of Shrewsbury. Her father was a schoolteacher who inspired his daughter with his own love of literature and the local countryside. On her mother’s side, she was descended from a family related to Sir Walter Scott. Webb loved to explore the countryside around her home and developed a gift of detailed observation and description, both of people and places, which infuses her poetry and prose.

At the age of 20, she developed symptoms of Graves’ disease, a thyroid disorder (resulting in bulging protuberant eyes and throat goitre), which caused ill health throughout her life and probably contributed to her early death.

In 1912, she married Henry Webb, a teacher who at first supported her literary interests. They lived for a time in Weston-super-Mare before moving back to her beloved Shropshire, where they worked as market gardeners until Henry secured a job as a teacher at the Priory School.

The couple lived briefly in Rose Cottage near the village of Pontesbury between the years 1914 and 1916, during which time she wrote The Golden Arrow. Her time in the village was commemorated in 1957 by the opening of the Mary Webb School.

The publication of The Golden Arrow in 1917 enabled them to move to Lyth Hill, Bayston Hill, a place Mary loved, buying a plot of land and building Spring Cottage.

In 1921, they bought a second property in London, hoping that she would be able to achieve greater literary recognition. This, however, did not happen. By 1927, she was suffering increasingly bad health, her marriage was failing and she returned to Spring Cottage alone.

She died at St. Leonards on Sea, aged 46.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Webb

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Max Weber

Max Weber

1864-1920

Karl Emil Maximilian “Max” Weber (April 21, 1864-June 14, 1920) was a German sociologist and political economist who profoundly influenced social theory, social research and the discipline of sociology itself.

Weber was a key proponent of methodological antipositivism, presenting sociology as a non-empiricist field that must study social action through interpretive means based upon understanding the meanings and purposes that individuals attach to their own actions.

Weber’s main intellectual concern was understanding the processes of rationalization, secularization and “disenchantment” that he associated with the rise of capitalism and modernity. Weber is perhaps best known for his thesis combining economic sociology and the sociology of religion, elaborated in his book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Weber proposed that ascetic Protestantism was one of the major “elective affinities” associated with the rise of capitalism, bureaucracy and the rational-legal nation-state in the Western world. Against Marx’s “historical materialism,” Weber emphasized the importance of cultural influences embedded in religion as a means for understanding the genesis of capitalism.

The Protestant Ethic formed the earliest part in Weber’s broader investigations into world religion: He would go on to examine the religions of China, the religions of India and ancient Judaism, with particular regard to the apparent non-development of capitalism in the corresponding societies, as well as to their differing forms of social stratification.

In another major work, Politics as a Vocation, Weber defined the state as an entity that successfully claims a “monopoly on the legitimate use of violence.” He was also the first to categorize social authority into distinct forms, which he labeled as charismatic, traditional and rational-legal. His analysis of bureaucracy emphasized that modern state institutions are increasingly based on rational-legal authority. Weber also made a variety of other contributions in economic history, as well as economic theory and methodology. Weber’s thought on modernity and rationalization would come to facilitate critical theory of the Frankfurt school.

After World War I, Max Weber was among the founders of the liberal German Democratic Party. He also ran unsuccessfully for a seat in parliament and served as adviser to the committee that drafted the ill-fated democratic Weimar Constitution of 1919.

After contracting the Spanish flu, he died of pneumonia in 1920, aged 56.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Weber

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Webster

John Webster

1580?-1625?

Very little is known about the life of John Webster. He was the son of a London carriage maker, John Webster, who was a member of the Merchant Taylors’ Company before being made free in 1571. His father was married on November 4, 1577, to Elizabeth Coates. It is assumed that John Webster was born soon after but, because the parish records were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, no accurate date exists.

It is possible that John Webster attended the respected Merchant Taylors’ School, but there is no evidence to the same. There is a record of a John Webster entered at Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court, in 1598, but it is not certain that he was John Webster, the playwright. It is, however, likely, considering Webster’s connections with Templars Sir Thomas Overbury, John Marston and John Ford, as well as his knowledge of law as evidenced later by his plays. Yet, whoever this Webster was, he was never called to the bar.

Webster started in the theatre working for Philip Henslowe. The first mention of Webster as a writer comes in 1602 when Anthony Munday, Michael Drayton, Thomas Middleton and John Webster were paid an advance for a now-lost play titled Caesar’s Fall (or Two Shapes). Webster’s first known work dates from 1604 when he wrote an “Induction” for the revival of John Marston’s The Malcontent, and collaborated with Thomas Dekker on Westward Ho, a citizen comedy, and on The Famous History of Sir Thomas Wyatt. The satire was answered by Jonson, Marston and Chapman in their Eastward Ho. The collaboration with Dekker continued with their retaliation, Northward Ho, in 1605. A historical play, Appius and Virginia (c. 1608), was probably a collaboration with Thomas Heywood. Webster’s first sole-authorship play was The Devil’s Law Case (c. 1610), a tragicomedy. This was followed by his two masterpieces, The White Devil (acted perhaps in 1608; printed 1612) and The Duchess of Malfi (before 1614; pub 1623), among the finest of all Jacobean tragedies.

Webster wrote a pageant, Monuments of Honour (1624), and collaborated with Middleton on Any Thing for a Quiet Life (c. 1621) and with William Rowley on A Cure for a Cuckold (c. 1624). Other plays are suspected to be lost. Webster is thought to have died sometime after 1625, but no certainty exists.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/webster/webbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Frank Wedekind

Frank Wedekind

1864-1918

Benjamin Franklin Wedekind (July 24, 1864, Hanover-March 9, 1918, Munich), usually known as Frank Wedekind, was a German playwright. His work, which often criticizes bourgeois attitudes (particularly toward sex), is considered to anticipate expressionism, and he was a major influence on the development of epic theatre.

He was born and lived most of his adult life in Munich, though he had a brief period working in advertising for the Maggi soup firm in Switzerland in 1886. Having initially worked in business and the circus, Wedekind went on to become an actor and singer. In this capacity he received wide acclaim as the principal star of the satirical cabaret, Die elf Scharfrichter (The Eleven Executioners), launched in 1901. It was thanks to Wedekind’s success that the tradition of German satirical writing was established in the theatre. At the age of 34, Wedekind became a dramaturg (a play-reader and adapter) at the Munich Schauspielhaus.

Wedekind’s first major play was Fruhlings Erwachen (Spring Awakening, 1891). The Lulu plays – Erdgeist (Earth Spirit, 1895) and Die Buchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1904) – are probably his best-known works.

Der Kammersanger (The Court-Singer, 1899) is a one-act character study of a famous opera singer who receives a series of unwelcome guests at his hotel suite. In Franziska (1910), the title character, a young girl, initiates a Faustian pact with the devil.

Wedekind also wrote a symbolist novella, Mine-Haha, or On the Bodily Education of Young Girls (1903).

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Wedekind

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Peter Weir

Peter Weir

1944-

The son of a real estate agent, Peter Weir was born in Sydney on August 21, 1944. After giving his father’s business a try, he spent time traveling around Europe. Upon his return to Australia, Weir secured a job with the Commonwealth Film Unit, where he learned his craft on the sets of documentaries and educational films.

He made his directorial debut in 1971 with Three to Go, an effort that went largely unnoticed by audiences and critics alike. His next feature, The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), was a horror comedy. Even more successful was Weir’s adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock the following year, followed by The Last Wave (1977).

Weir first achieved international recognition with Gallipoli in 1981. His reputation was further enhanced the next year with The Year of Living Dangerously. Next were Witness (1985), Dead Poets Society (1989) and Green Card.

After a disappointing reception for Fearless (1993), Weir rebounded strongly in 1998 with The Truman Show. Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World followed in 2003.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Weir

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

James Welch

James Welch

1940-2003

James Welch (1940-August 4, 2003) was an award-winning U.S. author and poet. He received national literary awards for Fools Crow. In addition, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas in 1997.

James Welch was born in Browning, Montana, in 1940. His father was a member of the Blackfeet tribe and his mother a member of the Gros Ventre tribe; both also had Irish ancestry. As a child, Welch attended schools on the Blackfoot and Fort Belknap reservations.

Welch went to the University of Montana, where he studied under the author Richard Hugo and began his writing career. Welch taught at the University of Washington and at Cornell, as well as serving on the Parole Board of the Montana Prisons Systems and on the Board of Directors of the Newberry Library D’Arcy McNickle Center.

Welch was at the University of Montana when his writing career began in earnest, leading to the creation of works that would establish his place in the Native American Renaissance literary movement.

Welch and Paul Stekler co-wrote the Emmy Award-winning American Experience documentary, Last Stand at Little Bighorn, shown on PBS. Together, they also wrote the history, Killing Custer: The Battle of Little Bighorn and the Fate of the Plains Indians (1994).

When Winter in the Blood was reprinted in 2007, it included an introduction by Louise Erdrich, who wrote: “It is a central and inspiring text to a generation of western regional and Native American writers, including me.”

Welch died at age 62 in his home in Missoula, Montana, in 2003.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Welch_%28writer%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Orson Welles

Orson Welles

1915-1985

Orson Welles was born George Orson Welles in Kenosha, Wisconsin, on May 6, 1915, the second son of Richard Welles, an inventor, and Beatrice Ives, a concert pianist. Welles was enrolled in the progressive Todd School in Woodstock, Illinois. There, he was first introduced to theater and learned a great deal about production and direction. His formal education ended with graduation in 1931.

After a short stay in Ireland, where Welles was involved in the theater as an actor, he returned to Chicago, where he briefly served as a drama coach at the Todd School and coedited four volumes of plays by William Shakespeare (1564-1616). He made his Broadway debut with Katharine Cornell’s company in December 1934. He and John Houseman (1902-1988) joined forces the next year to manage a unit of the Federal Theatre Project, one of the work-relief arts projects established by the New Deal.

Welles and Houseman organized the Mercury Theatre, which over the next two seasons had a number of extraordinary successes, including a modern-dress Julius Caesar, an Elizabethan working-class comedy, Shoemaker’s Holiday, and George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House. Welles also found time to play “The Shadow” on radio and to supervise Mercury Theatre on the Air, whose most notorious success was an adaptation of H.G. Wells’ (1866-1946) War of the Worlds.

In 1939, the Mercury Theatre collapsed as a result of economic problems and Welles went to Hollywood, California, where he filmed Citizen Kane in 1939 and 1940. Among his other films are: The Magnificent Ambersons (1942); The Lady from Shanghai (1946); Othello (1952); Touch of Evil (1958); The Trial (1962); and F Is for Fake (1973).

Welles died of a heart attack on October 10, 1985.

Source: http://www.notablebiographies.com/Tu-We/Welles-Orson.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

H.G. Wells

H.G. Wells

1866-1946

Sometimes called the father of modern science fiction, H.G. Wells was born on September 21, 1866 in Bromley, Kent, England. His father, a professional cricket player and shopkeeper, and his mother, a former lady’s maid, raised Wells with the idea that he would find a place in the working world that they were accustomed to. He aspired to a different place in society.

When he was 13, he left school to become a draper’s apprentice, a job his family expected would be proper for a boy of his station. The work repelled him, however. He worked briefly in a drugstore, returned for a stint as a draper’s assistant, then finally found a job as a teacher’s assistant in a grammar school. Education and academia suited him well. In 1884, he entered college with a scholarship to study biology. He was able to study under one of the great biology teachers of the time, Thomas Henry Huxley, and graduated in 1888.

The writings of Jules Verne undoubtedly influenced Wells and he wrote his first novel, The Time Machine, partly in response to this new kind of literature that Verne produced. The story appeared in various forms in magazines from 1888 to 1894 and was released in its current form in 1895. The book was successful and Wells did not need to teach or worry about money from that time on.

Wells’ early novels continued in the science fiction mode of The Time Machine. The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897) and The War between the Worlds (1898) cemented his position within the genre. Wells also wrote short stories, mainstream fiction and nonfiction essays his entire life, most of them espousing in some form or another his views on humanity, society and the direction he saw the world going. Some of these works were also science fictional in nature.

He died of unspecified causes on August 13, 1946, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, Regent’s Park, London, aged 79.

Source: http://www.sff.net/people/james.van.pelt/wells/biography.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

1862-1931

Ida B. Wells was born on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, during the second year of the Civil War. Her parents, James and Elizabeth Wells, were slaves and, thus, Wells, a woman who devoted her life to promoting racial equality, was born a slave. It was from her parents that Wells developed an interest in politics and her unwavering dedication to achieving set goals.

Determined to keep the family together after the death of her parents in 1878, Wells refused all attempts at splitting up her remaining siblings. Instead, she insisted on caring for her five siblings, despite the fact that she was 16, unemployed and poor. At the urging of the local Masonic lodge, she applied for a teaching position in the country. She adjusted her appearance so as to look older. She passed the qualifying examination and was given a position six miles away. Friends and relatives stayed with the Wells children during the week when Ida was away at school.

In 1883, Wells moved 40 miles north to Memphis and found employment at a school in Woodstock, Tennessee, about 10 miles outside the city. During her summer vacations, Wells took teachers’ training courses at Fisk University and at Lemoyne Institute. By the fall of 1884 she had qualified to teach in the city schools and was assigned a first-grade class, where she taught for seven years.

Wells’ career as a writer was sparked by an incident that occurred on May 4, 1884. While riding a train back to her job in Woodstock, Wells was asked by the conductor to move from her seat in the ladies’ car to the front of the train into the smoking car. When she refused, the conductor attempted to physically remove her from her seat. It took three men to remove Wells from her seat and, rather than move to the smoking car, she got off at the next stop to the cheers of the white passengers on the train. When Wells got back to Memphis, she immediately hired a lawyer to bring suit against the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company. The court returned a verdict in favor of Wells and awarded her $500 in damages. Wells wrote an article for The Living Way, a black church weekly. Her article was so well received that the editor of The Living Way asked for additional contributions. As a result, Wells began a weekly column, entitled Iola. By 1886, Wells’ articles were appearing in prominent black newspapers across the nation.

In 1892, Wells spoke at a conference of black women’s clubs, where she was given $500 to investigate lynching and publish her findings. Wells began investigating the fraudulent charges given as reasons to lynch black men. She found that many blacks were hung, shot and burned to death for trivial things such as not paying a debt, disrespecting whites, testifying in court, stealing hogs and public drunkenness. Her findings were published in a pamphlet, entitled “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” The New York Age began printing her articles and Wells launched a lecturing tour throughout the northeast to further spread her message on the horrors of lynching.

The remaining years of Ida B. Wells’ career were filled with more writing, activism and organizing. In 1909, she became one of the founders of the NAACP. In 1913, Wells established the first black women’s suffrage club, called the Alpha Suffrage Club. That same year, she marched in a suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., and met with President William McKinley about a lynching in South Carolina. During the years following World War I, she covered various race riots in Arkansas, East St. Louis and Chicago and published her reports in pamphlets and in The Conservator and newspapers nationwide.

Ida B. Wells died on March 25, 1931.

Source: http://www.webster.edu/~woolflm/idabwells.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Eudora Welty

Eudora Welty

1909-2001

Eudora Alice Welty (April 13, 1909-July 23, 2001) was an American author of short stories and novels about the American South. Welty was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, among numerous awards. She was the first living author to have her works published by the Library of America.

Welty was born in Jackson, Mississippi, the daughter of Christian Webb Welty and Mary Chestina (Andrews) Welty. Near the time of her high school graduation, Eudora moved with her family to a house built for them at 1119 Pinehurst Street, which would remain her permanent address until her death.

From 1925 to 1927, Welty studied at the Mississippi State College for Women, then transferred to the University of Wisconsin to complete her studies in English Literature. She studied advertising at Columbia University at the suggestion of her father. Because she graduated at the height of the Great Depression, she struggled to find work in New York. Soon after she returned to Jackson in 1931, her father died of leukemia. She took a job at a local radio station and wrote about Jackson society for the Tennessee newspaper, Commercial Appeal. In 1935, she began work for the Works Progress Administration. As a publicity agent, she collected stories, conducted interviews and took photographs of daily life in Mississippi. It was here that she got a chance to observe the Southern life and human relationships that she would later use in her short stories. During this time she also conducted meetings in her house with fellow writers and friends, a group she called the Night-Blooming Cereus Club. Three years later, she left her job to become a full-time writer.

In 1936, she published “The Death of a Traveling Salesman” in the literary magazine, Manuscript, and then proceeded to publish stories in several other notable publications, including The New Yorker. She solidified her place as an influential Southern writer when she penned her first book of short stories, A Curtain of Green.

She continued to write and won a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1973 for her novel, The Optimist’s Daughter. She also published a collection of photographs depicting the Great Depression, One Time, One Place, in 1971. She then lectured at Harvard University and eventually turned the speeches into a three-part book, One Writer’s Beginnings.

She continued to live in her family house in Jackson until her death on July 23, 2001.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eudora_Welty

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Dorothy West

Dorothy West

1907-1998

Dorothy West (June 2, 1907-August 16, 1998) was a novelist and short story writer who was part of the Harlem Renaissance. She is best known for her novel, The Living Is Easy, about the life of an upper-class black family.

West was born in Boston on June 2, 1907, to Isaac Christopher West, an emancipated slave who later became a successful businessman, and Rachel Pease Benson, one of 22 children. West reportedly wrote her first story at the age of 7. At age 14, she won several local writing competitions.

In 1926, West tied for second place in a writing contest sponsored by Opportunity, a journal published by the National Urban League, with her short story, “The Typewriter.” The person West tied with was future novelist Zora Neale Hurston.

Shortly before winning, West moved to Harlem with her cousin, the poet Helene Johnson. There West met other writers of the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and the novelist Wallace Thurman. Hughes gave West the nickname of “The Kid,” by which she was known during her time in Harlem.

West’s principal contribution to the Harlem Renaissance was to publish the magazine Challenge, which she founded in 1934 with $40. She also published the magazine’s successor, New Challenge. These magazines were among the first to publish literature featuring realistic portrayals of African-Americans. Among the works published were Richard Wright’s groundbreaking essay, “Blueprint for Negro Writing,” together with writings by Margaret Walker and Ralph Ellison.

After both magazines folded because of insufficient financing, West worked for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project until the mid-1940s. During this time she wrote a number of short stories for The New York Daily News. She then moved to Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, where she wrote her first novel, The Living Is Easy, in 1948.

In the next four decades, West worked as a journalist, primarily writing for a small newspaper on Martha’s Vineyard. In 1982, a feminist press brought The Living Is Easy back into print, giving new attention to West and her role in the Harlem Renaissance. As a result of this attention, at age 85, West finally finished a second novel, The Wedding, in 1995. The success of this novel resulted in the publication of a collection of West’s short stories and reminiscences, called The Richer, the Poorer.

West died on August 16, 1998, at the age of 91, one of the last surviving members of the Harlem Renaissance.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_West

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Nathanael West

Nathanael West

1903-1940

Nathanael West (born Nathan von Wallenstein Weinstein, October 17, 1903-December 22, 1940) was a U.S. author, screenwriter and satirist.

West was born in New York City, the first child of German-speaking Russian Jewish parents from Lithuania who maintained an upper-middle-class household in a Jewish neighborhood on the Upper West Side. West displayed little ambition in academics, dropping out of high school and only gaining admission into Tufts College by forging his high school transcript. After being expelled from Tufts, West got into Brown University by appropriating the transcript of a fellow Tufts student who was also named Nathan Weinstein. Although West did little schoolwork at Brown, he read extensively. He ignored the realist fiction of his American contemporaries in favor of French surrealists and British and Irish poets of the 1890s, in particular Oscar Wilde. West’s interests focused on unusual literary style as well as unusual content.

West barely finished at Brown with a degree. He then went to Paris for three months, and it was at this point that he changed his name to Nathanael West. West’s family, who had supported him thus far, ran into financial difficulties in the late 1920s. West returned home and worked sporadically in construction for his father, eventually finding a job as the night manager of the Hotel Kenmore Hall on East 23rd Street in Manhattan. One of West’s real-life experiences at the hotel inspired the incident between Romola Martin and Homer Simpson that would later appear in The Day of the Locust (1939).

Although West had been working on his writing since college, it was not until his quiet night job at the hotel that he found the time to put his novel together. It was at this time that West wrote what would eventually become Miss Lonelyhearts (1933). Maxim Lieber served as his literary agent in 1933.

In 1931, however, two years before he completed Miss Lonelyhearts, West published The Dream Life of Balso Snell, a novel he had conceived of in college.

In 1933, West bought a farm in eastern Pennsylvania but soon got a job as a contract scriptwriter for Columbia Pictures and moved to Hollywood. He published a third novel, A Cool Million, in 1934. None of West’s three works sold well, however, so he spent the mid-1930s in financial difficulty, sporadically collaborating on screenplays. It was at this time that West wrote The Day of the Locust. West took many of the settings and minor characters of his novel directly from his experience living in a hotel on Hollywood Boulevard.

On December 22, 1940, West and his wife, Eileen McKenney, were returning to Los Angeles from a hunting trip in Mexico. Possibly distraught over hearing of his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald’s death (Fitzgerald died on December 21 and his death was made known the next day), West ran a stop sign in El Centro, California, resulting in a collision in which he and McKenney were both killed. McKenney had been the inspiration for the title character in the Broadway play, My Sister Eileen, and she and West had been scheduled to fly to New York City for the Broadway opening on December 26. West was buried in Mount Zion Cemetery in Queens, New York, with his wife’s ashes placed in his coffin.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathanael_West

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Rebecca West

Rebecca West

1892-1983

Cicely Isabel Fairfield (December 21, 1892-March 15, 1983), known by her pen name Rebecca West, or Dame Rebecca West, was an English author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. She reviewed books for The Times, The New York Herald Tribune, The Sunday Telegraph and The New Republic and was a correspondent for The Bookman. Her major works include: Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), on the history and culture of Yugoslavia; A Train of Powder (1955), her coverage of the Nuremberg trials; The Meaning of Treason; The Return of the Soldier, a modernist World War I novel; and the Aubrey trilogy of autobiographical novels, The Fountain Overflows, This Real Night and Cousin Rosamund.