Author Biographies 17

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay

1892-1950

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892-October 19, 1950) was an American lyrical poet and playwright and the first woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. She was also known for her unconventional, bohemian lifestyle and her many love affairs. She used the pseudonym Nancy Boyd for her prose work.

Millay was born in Rockland, Maine, to Cora Lounella, a nurse, and Henry Tollman Millay, a schoolteacher who would later become superintendent of schools. Her middle name derives from St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York, where her uncle’s life had been saved just prior to her birth.

Cora taught her daughters to be independent and to speak their minds, which did not always sit well with the authority figures in Millay’s life. Millay preferred to be called “Vincent” rather than Edna, which she found plain.

At Camden High School, Millay began nurturing her budding literary talents, starting at the school’s literary magazine, The Megunticook, and eventually having some of her poetry published in the popular children’s magazine, St. Nicholas, The Camden Herald and, significantly, the anthology, Current Literature, all by the age of 15.

Millay’s career and celebrity began in 1912 when she entered her poem “Renascence” into a poetry contest in The Lyric Year. The poem was so widely considered the best submission that, when it was ultimately placed fourth, it was quite a scandal for which Millay received much publicity.

In New York, she lived in a number of places in Greenwich Village, including a house owned by the Cherry Lane Theatre that was renowned for being the smallest in New York City. It was at this time that she first attained great popularity in America. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923 for The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems. She was the first woman to be so honored for poetry. In 1943, she was awarded the Frost Medal for her lifetime contribution to American poetry. She was the sixth recipient of that honor and the second woman.

Millay was found dead at the bottom of the stairs in her house on October 19, 1950; it was clear she fell to her death but the cause of the fall is unknown.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edna_St._Vincent_Millay

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Arthur Miller

Arthur Miller

1915-2005

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915-February 10, 2005) was an American playwright and essayist. He was a prominent figure in American theatre, writing dramas that include plays such as: All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953) and A View from the Bridge (one-act, 1955; revised two-act, 1956).

Miller was born in Harlem, New York City, the second of three children of Isidore and Augusta Miller, Polish-Jewish immigrants. After graduating in 1932 from Abraham Lincoln High School, he worked at several menial jobs to pay for his college tuition.

At the University of Michigan, Miller first majored in journalism and worked as a reporter and night editor for the student paper, The Michigan Daily. It was during this time that he wrote his first play, No Villain. Miller switched his major to English and subsequently won the Avery Hopwood Award for No Villain. In 1937, Miller wrote Honors at Dawn, which also received the Avery Hopwood Award.

In 1938, Miller received a B.A. in English. After graduation, he began working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard while continuing to write radio plays, some of which were broadcast on CBS.

In 1940, Miller wrote The Man Who Had All the Luck, which was produced in New Jersey in 1940 and won the Theatre Guild’s National Award. In 1946, Miller’s play, All My Sons, was a success on Broadway and his reputation as a playwright was established. In 1948, Miller built a small studio in Roxbury, Connecticut. There, in less than a day, he wrote Act I of Death of a Salesman. Within six weeks, he completed the rest of the play.

In 1952, Miller traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, to research the witch trials of 1692. The Crucible, in which Miller likened the situation with the House Un-American Activities Committee to the witch hunt in Salem in 1692, opened on Broadway in 1953. In 1956, a one-act version of Miller’s verse drama, A View from the Bridge, opened on Broadway in a joint bill with one of Miller’s lesser-known plays, A Memory of Two Mondays. The following year, Miller revised A View from the Bridge as a two-act prose drama. Miller later began work on The Misfits.

In 1964, Miller’s next play, After the Fall, was produced. That same year, he produced Incident at Vichy. During this period, Miller wrote the penetrating family drama, The Price, produced in 1968.

Throughout the 1970s, Miller spent much of his time experimenting with the theatre, producing one-act plays such as Fame and The Reason Why, and producing In The Country and Chinese Encounters. Both his 1972 comedy, The Creation of the World and Other Business, and its musical adaptation, Up from Paradise, were critical and commercial failures. In 1978, he published a collection of his Theater Essays.

During the early 1990s, Miller wrote three new plays, The Ride Down Mt. Morgan (1991), The Last Yankee (1992) and Broken Glass (1994). Mr. Peters’ Connections was staged Off-Broadway in 1998. Miller’s final play, Finishing the Picture, opened at the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, in the fall of 2004.

He died of heart failure after a battle against cancer, pneumonia and congestive heart disease at his home in Roxbury, Connecticut, on the evening of February 10, 2005.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Miller

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Henry Miller

Henry Miller

1891-1980

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891-June 7, 1980) was an American novelist and painter. He was known for breaking with existing literary forms and developing a new sort of “novel” that is a mixture of novel, autobiography, social criticism, philosophical reflection, surrealist free association and mysticism, one that is distinctly always about and expressive of the real-life Henry Miller and yet is also fictional.

Miller was born to tailor Heinrich Miller and Louise Marie Neiting, in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, New York City, of German Catholic heritage. He briefly – for only one semester – attended the City College of New York. In late 1931, Miller was employed by The Chicago Tribune (Paris edition) as a proofreader.

In 1940, Miller settled in Big Sur, California. He continued to produce vividly written works that challenged contemporary American cultural values and moral attitudes. He was widely critical of consumerism in America, as reflected in Sunday after the War (1944) and The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945). He spent the last years of his life at his home at 444 Ocampo Drive, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, California.

The publication of Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in the United States in 1961 led to a series of obscenity trials that tested American laws on pornography. The U.S. Supreme Court, in Grove Press, Inc., v. Gerstein, citing Jacobellis v. Ohio (which was decided the same day in 1964), overruled the state court findings of obscenity and declared the book a work of literature.

In addition to his literary abilities, Miller produced numerous watercolor paintings and wrote books on this field.

Miller died of circulatory complications in Pacific Palisades in 1980 at the age of 88.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Miller

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Steven Millhauser

Steven Millhauser

1943-

Steven Millhauser (born August 3, 1943) is an American novelist and short story writer. He won the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his novel, Martin Dressler. The prize brought many of his older books back into print.

Millhauser was born in New York City, grew up in Connecticut and earned a B.A. from Columbia University in 1965. He then pursued a doctorate in English at Brown University. He never completed his dissertation but wrote parts of Edwin Mullhouse and From the Realm of Morpheus in two separate stays at Brown. Between times at the university, he wrote Portrait of a Romantic at his parents’ house in Connecticut. His story, “The Invention of Robert Herendeen” (in The Barnum Museum), features a failed student who has moved back in with his parents; the story is loosely based on this period of Millhauser’s life.

Until the Pulitzer Prize, Millhauser was best known for his 1972 debut novel, Edwin Mullhouse. Millhauser followed with a second novel, Portrait of a Romantic, in 1977, and his first collection of short stories, In the Penny Arcade, in 1986.

Possibly the most well-known of his short stories is “Eisenheim the Illusionist,” based on a pseudo-mythical tale of a magician who stunned audiences in Vienna in the latter part of the 19th century.

Millhauser’s collections of stories continued with The Barnum Museum (1990), Little Kingdoms (1993) and The Knife Thrower and Other Stories (1998). Dangerous Laughter: Thirteen Stories made The New York Times Book Review list of “10 Best Books of 2008.”

Millhauser lives in Saratoga Springs, New York, and teaches at Skidmore College.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Millhauser

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

John Milton

John Milton

1608-1674

John Milton was born on December 9, 1608, on Bread Street in London, England, to Sarah Jeffrey (1572-1637) and John Milton (1562-1647), scrivener in legal and financial matters. Milton was born with poor eyesight, which increasingly worsened over time. A lifelong student, his schooling started at home under tutor Thomas Young before he went to read the works of Homer and Virgil in Greek and Latin at St. Paul’s School in London.

He entered Christ’s College, Cambridge, in 1625, with the intent to become a minister. However, upon graduation in 1632 with a Master of Arts degree, Milton was disenchanted with the Church, did not take his orders and decided to further his studies in languages, including Hebrew. He also learned French and Italian, countries he travelled through extensively in the late 1630s, where he immersed himself in their history and culture and met many prominent learned men of the time, including Galileo Galilei (1564-1642).

Upon his return to England from the continent in 1639, he moved to his parents’ home in Horton, Buckinghamshire, to focus on further study and writing. Some of his earliest pieces were metrical psalms and poems, such as “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity” (1629), “An Epitaph on the Admirable Dramatic Poet William Shakespeare” (1630) and “Il Penseroso” (1631) and its companion piece, “L’Allegro” (1631).

He also wrote the masques Arcades (c. 1630-34) and Comus (1634), and his eloquent elegy, “Lycidas” (1637). Around this time, Milton began teaching and joined the Presbyterian cause to reform the Church and wrote several pamphlets, including “Of Reformation” (1641) and “The Reason of Church Government Urged against Prelaty” (1642). Poems was published in 1645.

In 1649, after the regicide of King Charles I, Milton was appointed Cromwell’s Latin secretary of foreign affairs and wrote many pamphlets in defense of the Commonwealth. The intense work of translating and writing created much strain on his eyes and he resorted to a secretary. By 1652, he was entirely blind and relied on the assistance of Andrew Marvell (1621-1678), but it seems that Milton was not unduly grieved by his loss of sight.

After the death of Cromwell and the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660, Milton retired from public life. A staunch defender of the Commonwealth, he first had to hide entirely from King Charles’ loyalists and some of his books were burned. The Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed the Bread Street house where he was born and that he had inherited from his father. During the plague years, he left London for surrounding areas; his cottage in the village of Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, and its gardens are now a museum housing many of his works. It was here that Milton prepared for publication both Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained, which also includes his poetic drama, Samson Agonistes (1671), wherein he reflects on his own life once again under the monarchy.

John Milton died on November 12, 1674, in Artillery Row, London. His On Christian Doctrine was published in 1823.

Source: http://www.online-literature.com/milton/

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Anthony Minghella

Anthony Minghella

1954-2008

Anthony Minghella (January 6, 1954-March 18, 2008) was an English film director, playwright and screenwriter.

He won the Academy Award for Best Director for The English Patient (1996), which also won the BAFTA Award for Best Film and Golden Globe Award for Best Director.

Minghella was born in Ryde, Isle of Wight, the son of Gloria (nee Arcari) and Edward Minghella, ice cream factory owners. His father was an Italian immigrant and his mother was born in Leeds to an Italian family.

Minghella attended Sandown Grammar School and St. John’s, Portsmouth. He graduated from the University of Hull, where he completed undergraduate and postgraduate courses, but eventually abandoned his doctoral thesis.

His first piece of produced work was a 1975 stage adaptation of Gabriel Josipovici’s Mobius the Stripper and it was his 1985 piece, Whale Music, that fueled his career. He made his directorial debut with a double bill of Samuel Beckett’s Play and Happy Days. His first feature film as a director was A Little Like Drowning in 1978.

During the 1980s, he worked in television, starting as a runner on Magpie before moving into script editing for the children’s drama series, Grange Hill, for the BBC, later writing The Storyteller series for Jim Henson. He also wrote several episodes of the ITV detective drama, Inspector Morse, and an episode of the long-running ITV drama, Boon. His 1986 play, Made in Bangkok, found mainstream success in the West End.

Minghella’s 1990 feature, Truly, Madly, Deeply, a drama he had written and directed for the BBC’s Screen Two anthology strand, bypassed its expected TV broadcast and received a cinema release. In order to make the film, he had turned down an offer to direct another episode of Inspector Morse, which he had thought would be a much higher-profile assignment.

In 1996, he won the Academy Award for Best Director for The English Patient. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Adapted Screenplay for 1999’s The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Minghella died of a hemorrhage on March 18, 2008 in Charing Cross Hospital, London, following an operation the previous week to remove cancer of the tonsils and neck.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Minghella

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Susan Minot

Susan Minot

1956-

Susan Minot (born December 7, 1956) is a prize-winning American novelist and short story writer.

Minot was born in Boston, Massachusetts. She graduated from Concord Academy and then attended Brown University, where she studied writing and painting; in 1983, she graduated from Columbia University School of the Arts with an M.F.A. in creative writing. Her first book, Monkeys, won the 1987 Prix Femina Etranger. She has also received an O. Henry Prize and a Pushcart Prize for her writing.

Sexuality and the difficulties of romantic relationships are a constant theme in Minot’s work. Her second book, Lust and Other Stories, focuses on “the relations between men and women in their 20s and 30s having difficulty coming together and difficulty breaking apart.”

Minot has also co-authored two screenplays that have been made into films: Stealing Beauty (1996), with Bernardo Bertolucci, and Evening (based on her novel of the same name, 2007), written with Michael Cunningham.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susan_Minot

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Yukio Mishima

Yukio Mishima

1925-1970

Yukio Mishima (January 14, 1925-November 25, 1970) is one of the most widely read Japanese authors of the 20th century, due in part to his dramatic suicide in 1970. Born in Tokyo, Mishima studied law and was a civil servant before turning to writing exclusively.

Over his career he was incredibly prolific, a writer of novels, short stories, plays and political and literary criticism, beginning in the late 1940s. Nominated for the Nobel Prize three times, his most famous books include: Gogo no eiko (1965, The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea), Kinkakuji (1956, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) and the tetralogy, Hojo no umi (1965-71, The Sea of Fertility).

His personal life got just as much attention as his writing: After a 1952 trip to Greece, Mishima began a strict regimen of body-building and became keen on photographing his chiseled physique in poses reminiscent of the death of the Christian martyr, St. Sebastian. He also became obsessed with loyalty to the emperor and formed his own small army, called the Shield Society.

On November 25, 1970, he delivered the complete manuscript of the last work in his tetralogy, then proceeded with four followers to the headquarters of the Japanese Self-Defense Force, where he read a “manifesto” and then committed seppuku (ritual disembowelment), after which one of his compatriots chopped his head off.

Source: http://www.infoplease.com/biography/var/yukiomishima.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Donald Mitchell

Donald Mitchell

1822-1908

Donald Grant Mitchell (April 12, 1822-December 15, 1908) was an American essayist and novelist.

Mitchell, the grandson of politician and jurist Stephen Mix Mitchell, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. He graduated from Yale College in 1841, where he was a member of Skull and Bones and studied law, but he soon took up literature. Throughout his life, he showed a particular interest in agriculture and landscape gardening, which he followed at first in pursuit of health. He served as U.S. consul at Venice, Italy, from 1853 to 1854, and in 1855 he settled at his estate, called Marvelwood, near New Haven, Connecticut.

He was best known as the author (under the pseudonym of “Ik Marvel”) of the sentimental essays contained in the volumes Reveries of a Bachelor, or a Book of the Heart (first published in book form in 1850) and Dream Life, a Fable of the Seasons (1851).

Mitchell produced books of travel, volumes of essays on rural themes, including Reveries of a Bachelor (1850) and My Farm of Edgewood: A Country Book (1863); sketch studies of English monarchs and of English and American literature; and a character novel, Doctor Johns (1866). His other works include About Old Story-Tellers (1878) and American Lands and Letters (1897-1899).

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Grant_Mitchell

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Mitchell

1900-1949

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell (November 8, 1900-August 16, 1949) was an American author and journalist. One novel by Mitchell was published during her lifetime, the American Civil War-era epic, Gone with the Wind. For it she won the National Book Award for Most Distinguished Novel of 1936 and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1937.

Mitchell was a Southerner and a lifelong resident and native of Atlanta, Georgia, who was born in 1900 into a wealthy and politically prominent family. Her father, Eugene Muse Mitchell, was an attorney, and her mother, Mary Isabel “May Belle” (or “Maybelle”) Stephens, was a suffragist.

In Mitchell’s teenage years, she is known to have written a novel about girls in a boarding school, The Big Four; a story about “Little Sister” who hears her older sister being raped and shoots the rapist; and a romance novella that takes places on a South Pacific island, Lost Laysen. Mitchell gave Lost Laysen, which she had written in two notebooks, to a boyfriend, Henry Love Angel. He died in 1945 and the novella remained undiscovered among some letters she had written to him until 1994. In the 1920s, she completed a novelette, Ropa Carmagin, about a Southern white girl who loves a biracial man. She also started another story set in the Jazz Age of the 1920s but did not complete it.

Margaret Mitchell was struck by a speeding automobile as she crossed Peachtree Street at 13th Street in Atlanta with her husband, John Marsh, while on her way to see a movie on the evening of August 11, 1949. She died at Grady Hospital five days later without regaining consciousness.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Mitchell

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Jean-Baptiste Moliere

Jean-Baptiste Moliere

1622-1673

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, known by his stage name Moliere, (baptized January 15, 1622-February 17, 1673) was a French playwright and actor who is considered to be one of the greatest masters of comedy in Western literature.

Among Moliere’s best-known works are Le Misanthrope (The Misanthrope), L’Ecole des femmes (The School for Wives), Tartuffe ou L’Imposteur, (Tartuffe, or the Hypocrite), L’Avare (The Miser), Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid) and Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (The Bourgeois Gentleman).

Born into a prosperous family and having studied at the College de Clermont, Moliere was well suited to begin a life in the theatre. Thirteen years as an itinerant actor helped him polish his comic abilities while he began writing, combining Commedia dell’arte elements with the more refined French comedy.

Through the patronage of a few aristocrats, including Philippe I, Duke of Orleans – the brother of Louis XIV – Moliere procured a command performance before the king at the Louvre. Performing a classic play by Pierre Corneille and a farce of his own, Le Docteur amoureux (The Doctor in Love), Moliere was granted the use of salle du Petit-Bourbon near the Louvre, a spacious room appointed for theatrical performances. Later, Moliere was granted the use of the Palais-Royal. In both locations, he found success among the Parisians with plays such as Les Precieuses ridicules (The Affected Ladies), L’Ecole des maris (The School for Husbands) and L’Ecole des femmes (The School for Wives). This royal favor brought a royal pension to his troupe and the title “Troupe du Roi” (“The King’s Troupe”). Moliere continued as the official author of court entertainments.

Though he received the adulation of the court and Parisians, Moliere’s satires attracted criticisms from moralists and the Roman Catholic Church. Tartuffe ou L’Imposteur (Tartuffe, or the Hypocrite) and its attack on religious hypocrisy roundly received condemnations from the Church, while Dom Juan was banned from performance.

Moliere’s hard work in so many theatrical capacities began to take its toll on his health and, by 1667, he was forced to take a break from the stage. In 1673, during a production of his final play, Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid), Moliere, who suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, was seized by a coughing fit and a haemorrhage while playing the hypochondriac Argan. He finished the performance but collapsed again and died a few hours later.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moli%C3%A8re

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Navarre Scott Momaday

Navarre Scott Momaday

1934-

Navarre Scott Momaday (born February 27, 1934) is a Kiowa-Cherokee Pulitzer Prize-winning writer from Oklahoma, New Mexico and Arizona.

He is the son of the writer, Natachee Scott Momaday, and the painter, Al Momaday, and was born at the Kiowa-Comanche Indian Hospital in Lawton, Oklahoma. He is enrolled in the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma but also has Cherokee heritage from his mother.

Momaday’s novel, House Made of Dawn, led to the breakthrough of Native American literature into the mainstream. It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1969.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N._Scott_Momaday

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

1690-1762

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (May 15, 1689-August 21, 1762) was an English aristocrat and writer. Montagu is today chiefly remembered for her letters, particularly her letters from Turkey, as wife to the British ambassador.

Lady Mary Pierrepont was born in London; her baptism took place on May 26 at St. Paul’s Church in Covent Garden. She began her education in her father’s home. She used the library in her father’s mansion, Thoresby Hall in the Dukeries of Nottinghamshire, to “steal” her education, teaching herself Latin.

In 1712, she married Edward Wortley Montagu. The early years of her marriage were spent in seclusion in the country. Her husband became Member of Parliament for Westminster in 1715 and, shortly afterward, was made a Lord Commissioner of the Treasury. When Lady Mary joined him in London, her wit and beauty soon made her a prominent figure at court. She was among the society of George I and the Prince of Wales, and friends with Alexander Pope, John Gay and Abbe Antonio Conti.

In December 1715, Lady Wortley Montagu contracted smallpox but survived. Early in 1716, Edward Wortley Montagu was appointed Ambassador at Constantinople. Lady Mary accompanied him to Vienna, and thence to Adrianople and Constantinople. He was recalled in 1717, but they remained at Constantinople until 1718. After an unsuccessful delegation between Austria and the Ottoman empires, they returned to England.

The story of this voyage and of her observations of Eastern life is told in the Turkish Embassy Letters, a series of lively letters full of graphic descriptions. Lady Mary returned to the West with knowledge of the Ottoman practice of inoculation against smallpox, known as variolation. In the 1790s, Edward Jenner developed a safer method, vaccination.

In 1739, she left her husband and went abroad and, although they continued to write to each other in affectionate and respectful terms, they never met again. She eventually divorced him. In 1740, Lady Mary was in her 63rd year and lived at Avignon, at Brescia, at Gottolengo and at Lovere on the Lago d’Iseo. She was disfigured by a painful skin disease (resulting from smallpox) and her sufferings were so acute that she hints at the possibility of madness. She was struck with a terrible fit of sickness while visiting the countess Palazzo and her son, and perhaps her mental condition made restraint necessary.

Her daughter, Mary, Countess of Bute, whose husband was now Prime Minister, begged her to return to England. She came to London and died on August 21, 1762.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Mary_Wortley_Montagu

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Michel Montaigne

Michel Montaigne

1533-1592

Lord Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (February 28, 1533-September 13, 1592) was one of the most influential writers of the French Renaissance, known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre and is popularly thought of as the father of Modern Skepticism. He became famous for his effortless ability to merge serious intellectual speculation with casual anecdotes and autobiography – and his massive volume Essais (translated literally as Attempts) contains, to this day, some of the most widely influential essays ever written.

Montaigne was born in the Aquitaine region of France, on the family estate Chateau de Montaigne, in a town now called Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, not far from Bordeaux. Around the year 1539, he was sent to study at a prestigious boarding school in Bordeaux, the College de Guyenne, then under the direction of the greatest Latin scholar of the era, George Buchanan, where he mastered the whole curriculum by his 13th year. He then studied law in Toulouse and entered a career in the legal system. He was a counselor of the Court des Aides of Perigueux and, in 1557, he was appointed counselor of the Parlement in Bordeaux (a high court).

In 1571, he retired from public life to the Tower of the Chateau, his so-called “citadel,” in the Dordogne, where he almost totally isolated himself from every social and family affair. Locked up in his library, which contained a collection of some 1,500 works, he began work on his Essais, first published in 1580.

Montaigne died of quinsy at the age of 59, in 1592, at the Chateau de Montaigne and was buried nearby.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_de_Montaigne

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lucy Maud Montgomery

Lucy Maud Montgomery

1874-1942

Lucy Maud Montgomery (November 30, 1874-April 24, 1942), called “Maud” by family and friends and publicly known as L.M. Montgomery, was a Canadian author best known for a series of novels beginning with Anne of Green Gables, published in 1908, followed by a series of sequels. Montgomery went on to publish 20 novels as well as 500 short stories and poems.

Montgomery was born in Clifton (now New London), Prince Edward Island. Her first work was published in the Charlottetown paper, Daily Patriot, in November 1890.

Montgomery worked as a teacher in various island schools. She did not enjoy her teaching career but she was content because it afforded her time to write. Beginning in 1897, she began to have her short stories published in various magazines and newspapers. A prolific talent, Montgomery had more than 100 stories published from 1897 to 1907.

In 1898, Montgomery moved back to Cavendish to live with her widowed grandmother. For a short time in 1901 and 1902, she worked in Halifax for the newspapers Chronicle and Echo. She returned to live with her grandmother in 1902. Montgomery was inspired to write her first books during this time on Prince Edward Island. Over the next 13 years, Montgomery stayed in Cavendish to take care of her grandmother. This coincided with period of considerable income from her publications.

In 1908, Montgomery published her first book, Anne of Green Gables. Three years later, shortly after her grandmother’s death, she married Ewan Macdonald (1870-1943), a Presbyterian minister, and they moved to Ontario, where he had taken the position of minister of St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Leaskdale in present-day Uxbridge Township, also affiliated with the congregation in nearby Zephyr.

In the last year of her life, Montgomery completed what she intended to be a ninth book featuring Anne, titled The Blythes Are Quoted. It included 15 short stories, 41 poems and vignettes featuring the Blythe family members discussing the poems.

Montgomery suffered from depression and took her own life via a drug overdose.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucy_Maud_Montgomery

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Alan Moore

Alan Moore

1953-

Alan Oswald Moore (born November 18, 1953) is an English writer primarily known for his work in comic books, a medium in which he has produced a number of critically acclaimed and popular series, including Watchmen, V for Vendetta and From Hell. He has occasionally used such pseudonyms as Curt Vile, Jill de Ray and Translucia Baboon.

Moore started out writing for British underground and alternative fanzines in the late 1970s before achieving success publishing comic strips in such magazines as 2000AD and Warrior. He was subsequently picked up by the American DC Comics and, as “the first comics writer living in Britain to do prominent work in America,” he worked on big-name characters such as Batman (Batman: The Killing Joke) and Superman (Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?), substantially developed the minor character Swamp Thing and penned original titles, such as Watchmen.

During that decade, Moore helped to bring about greater social respectability for the medium in the United States and United Kingdom and has subsequently been attributed with the development of the term “graphic novel” over “comic book.”

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, he left the comic industry mainstream and went independent for a while, working on experimental work such as the epic, From Hell, pornographic Lost Girls and the prose novel, Voice of the Fire. He subsequently returned to the mainstream later in the 1990s, working for Image Comics, before developing America’s Best Comics, an imprint through which he published works such as The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and the occult-based, Promethea.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Brian Moore

Brian Moore

1921-1999

Brian Moore (August 25, 1921-January 11, 1999) was a Northern Irish novelist and screenwriter who emigrated to Canada and later lived in the United States. He was acclaimed for the descriptions in his novels of life in Northern Ireland after World War II, in particular his explorations of the inter-communal divisions of The Troubles. He was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1975, the inaugural Sunday Express Book of the Year award in 1987 and was short-listed for the Booker Prize three times. Moore also wrote screenplays and several of his books were made into films.

Moore was born and grew up in Belfast. His father was a surgeon and his mother was a nurse. He was a volunteer air raid warden during the bombing of Belfast by the Luftwaffe. He also served as a civilian with the British Army in North Africa, Italy and France. After the war ended, he worked in Eastern Europe for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. He emigrated to Canada in 1948, worked as a reporter for The Montreal Gazette and became a Canadian citizen.

Moore lived in Canada from 1948 to 1958 and wrote his first novels there. His earliest novels were thrillers, published under his own name or using the pseudonyms Bernard Mara or Michael Bryan. Moore’s first novel outside the genre, Judith Hearne, remains among his most highly regarded.

Other novels by Moore were adapted for the screen, including Intent to Kill, The Luck of Ginger Coffey, Catholics, Black Robe, Cold Heaven and The Statement. He co-wrote the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain and wrote The Blood of Others, based on the novel Le Sang des autres by Simone de Beauvoir.

Brian Moore died in 1999 at his home in Malibu, California, aged 77, from pulmonary fibrosis.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Moore_%28novelist%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Clement Clarke Moore

Clement Clarke Moore

1779-1863

Clement Clarke Moore (July 15, 1779-July 10, 1863) was a professor of Oriental and Greek literature at Columbia College, now Columbia University. He is generally considered to be the author of the yuletide poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”

He was born to Benjamin Moore and Charity Clarke. Moore was a graduate of Columbia College (1798), where he earned both his B.A. and his M.A.

In 1820, Moore helped Trinity Church organize a new parish church, St. Luke in the Fields, on Hudson Street, and the following year he was made professor of Biblical learning at the General Theological Seminary in New York, a post that he held until 1850. The ground on which the seminary now stands was his gift.

From 1840 to 1850, he was a board member of the New York Institution for the Blind at 34th Street and Ninth Avenue, which is now the New York Institute for Special Education. He compiled a two-volume Hebrew and English Lexicon (1809) and published a collection of poems (1844). Upon his death in 1863, at his summer residence in Newport, Rhode Island, his funeral was held in Trinity Church, Newport, where he had owned a pew. Then his body was interred in the cemetery at St. Luke in the Fields. On November 29, 1899, his body was reinterred in Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in New York.

Moore opposed the abolition of slavery and owned several slaves during his lifetime.

The poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” “arguably the best-known verses ever written by an American,” was first published anonymously in the Troy, New York, Sentinel on December 23, 1823, and was reprinted frequently thereafter with no name attached. Moore later acknowledged authorship and the poem was included in an 1844 anthology of his works at the insistence of his children, for whom he wrote it.

“A Visit from St. Nicholas” is largely responsible for the conception of Santa Claus from the mid-19th century to today, including his physical appearance, the night of his visit, his mode of transportation, the number and names of his reindeer and the tradition that he brings toys to children. Prior to the poem, American ideas about St. Nicholas and other Christmastide visitors varied considerably. The poem has influenced ideas about St. Nicholas and Santa Claus beyond the United States to the rest of the English-speaking world and beyond.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_Clarke_Moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

G.E. Moore

G.E. Moore

1873-1958

George Edward Moore (November 4, 1873-October 24, 1958) was an English philosopher. He was, with Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein and (before them) Gottlob Frege, one of the founders of the analytic tradition in philosophy. Along with Russell, he led the turn away from idealism in British philosophy and became well known for his advocacy of common-sense concepts, his contributions to ethics, epistemology and metaphysics.

Moore was educated at Dulwich College and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he read Classics and Moral Sciences. He became a Fellow of Trinity in 1898 and went on to hold the University of Cambridge chair of mental philosophy and logic from 1925 to 1939.

Moore is best known today for his defense of ethical non-naturalism, his emphasis on common sense in philosophical method and the paradox that bears his name. He was admired by and influential among other philosophers, and also by the Bloomsbury Group, but is (unlike his colleague Russell) mostly unknown today outside of academic philosophy. Moore’s essays are known for their clear, circumspect writing style and for he is known for his methodical and patient approach to philosophical problems. He was critical of modern philosophy for its lack of progress, which he believed was in stark contrast to the dramatic advances in the natural sciences since the Renaissance. He often praised the analytic reasoning of Thales of Miletus, an early Greek philosopher, for his analysis of the meaning of the term “landscaping.” Moore thought Thales’ reasoning was one of the few historical examples of philosophical inquiry resulting in practical advances.

Among Moore’s most famous works are his book, Principia Ethica, and his essays, “The Refutation of Idealism,” “A Defence of Common Sense” and “A Proof of the External World.”

G.E. Moore died on October 24, 1958.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._E._Moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

George Augustus Moore

George Augustus Moore

1852-1933

George Augustus Moore (February 24, 1852-January 21, 1933) was born at Moore Hall, Ballyglass, County Mayo, the eldest son of George Henry Moore, Nationalist MP, Catholic landowner, racehorse trainer and one-time friend of Maria Edgeworth.

Moore briefly attended Oscott College, a minor Catholic public school near Birmingham. Left unsupervised and largely in the company of stable boys at Moore Hall, he nurtured the ambition of becoming a jockey. Spared a military career by his father’s death, and heir to 12,000 acres, Moore left for Paris in 1873, determined to be a painter. Moore came to realize that he had little talent for painting and decided to write instead.

Poor harvests and rent failures in the west of Ireland forced Moore to return to England in late 1879. Having begun as a poet, he turned to prose and resolved to follow Emile Zola’s naturalistic experiments. His first novel, A Modern Lover, was published in 1883, followed by: A Mummer’s Wife (1885); A Drama in Muslin (1886); Parnell and His Island (1887), a collection of bitterly satirical essays; and The Confessions of a Young Man (1888).

Moore wrote articles about literature and art for a number of magazines, later collected as Impressions and Opinions (1889) and Modern Painting (1893). He published two unsuccessful novels, Mike Fletcher (1889) and Vain Fortune (1891), but with the publication of Esther Waters (1894) he established himself as a writer with a keen awareness of the vulnerability of women in society. He made no attempt to repeat his success. Instead, he tried his hand as a playwright and continued to experiment with short fiction, as in Celibates (1895), a book of stories about people whom life has overcome. He also embarked on two musical novels, Evelyn Innes (1898) and Sister Teresa (1901).

Though not an Irish-speaker himself, he threw himself behind the language movement, writing The Untilled Field (1903) for translation into Irish, to be used by the Gaelic League. He then wrote The Lake (1905) and Hail and Farewell.

Moore spent the remaining 23 years of his life at 121 Ebury St. In 1913, he travelled to the Holy Land to research the background for The Brook Kerith (1916). Among his later works are: A Story-Teller’s Holiday (1918), Heloise and Abelard (1921), and the conversational memoirs, Avowals (1919) and Conversations in Ebury Street (1924).

While writing Aphrodite in Aulis, he became ill with uraemia and died on January 21, 1933.

Source: http://www.answers.com/topic/george-moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lorrie Moore

Lorrie Moore

1957-

Lorrie Moore (born Marie Lorena Moore on January 13, 1957) is an American fiction writer known mainly for her humorous and poignant short stories.

Moore was born in Glens Falls, New York, and nicknamed “Lorrie” by her parents. She attended St. Lawrence University. At 19, she won Seventeen magazine’s fiction contest. After graduating from St. Lawrence, she moved to Manhattan and worked as a paralegal for two years.

In 1980, Moore enrolled in Cornell University’s M.F.A. program. Upon graduation from Cornell, Moore was encouraged by a teacher to contact agent Melanie Jackson. Jackson sold her collection, Self-Help, composed almost entirely of stories from her master’s thesis, to Knopf in 1983.

Her short story collections are: Self-Help, Like Life and Birds of America. She has contributed to The Paris Review. Her first story to appear in The New Yorker, “You’re Ugly, Too,” was later included in The Best American Short Stories of the Century. Another story, “People Like That Are the Only People Here,” also published in The New Yorker, was reprinted in the 1998 edition of the annual collection, The Best American Short Stories.

Moore’s novels are Anagrams (1986), Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? (1994) and A Gate at the Stairs (2009). She has also written a children’s book, The Forgotten Helper.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorrie_Moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Marianne Moore

Marianne Moore

1887-1972

Marianne Moore (November 15, 1887-February 5, 1972) was an American Modernist poet and writer noted for her irony and wit.

Moore was born in Kirkwood, Missouri, in the manse of the Presbyterian church, where her maternal grandfather, John Riddle Warner, served as pastor. She was the daughter of construction engineer and inventor, John Milton Moore, and his wife, Mary Warner. She grew up in her grandfather’s household, her father having left the family before her birth. In 1905, Moore entered Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and graduated four years later. She taught at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, until 1915, when she began to publish poetry professionally.

Moore came to the attention of poets as diverse as Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, H.D., T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound beginning with her first publication in 1915. From 1925 until 1929, Moore served as editor of the literary and cultural journal, The Dial. This continued her role, similar to that of Pound, as a patron of poetry; much later, she encouraged promising young poets, including Elizabeth Bishop, Allen Ginsberg, John Ashbery and James Merrill.

In 1933, Moore was awarded the Helen Haire Levinson Prize for Poetry. Her Collected Poems of 1951 is perhaps her most-rewarded work; it earned the poet the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award and the Bollingen Prize. Her most famous poem is perhaps the one entitled, appropriately, “Poetry,” in which she hopes for poets who can produce “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.”

Moore moved to 35 West 9th Street in Manhattan in 1966 after living half a century at 260 Cumberland Street in Brooklyn. Not long after throwing the first pitch for the 1968 season in Yankee Stadium, Moore suffered a stroke. She suffered a series of strokes thereafter and died in 1972. She was interred in Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marianne_Moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Moore

Thomas Moore

1779-1852

Thomas Moore (May 28, 1779-February 25, 1852) was an Irish poet, singer, songwriter and entertainer, now best remembered for the lyrics of “The Minstrel Boy” and “The Last Rose of Summer.”

Born on the corner of Aungier Street in Dublin, Ireland, over his father’s grocery shop, he was educated at Trinity College, which had recently begun accepting Catholic students, and he studied law at the Middle Temple in London.

It was as a poet, translator, balladeer and singer that he found fame. His work soon became immensely popular and included “The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls,” “Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” “The Meeting of the Waters” and many others. His ballads were published as Moore’s Irish Melodies (commonly called Moore’s Melodies) in 1846 and 1852.

Moore was far more than a balladeer. He had major success as a society figure in London and, in 1803, was appointed registrar to the Admiralty in Bermuda. From there, he travelled in Canada and the United States. It was after this trip that he published his book, Epistles, Odes and Other Poems, which featured a paean to the historic Cohoes Falls called “Lines Written at the Cohos, or Falls of the Mohawk River,” among other famous verses.

He finally settled in Sloperton Cottage at Bromham, Wiltshire, England, and became a novelist and biographer as well as a successful poet. He received a state pension but his personal life was dogged by tragedy, including the deaths of all of his five children within his lifetime and the suffering of a stroke in later life, which disabled him from performances – the activity at which he was most renowned.

His remains are in the vault at St. Nicholas, Bromham.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Moore

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Pat Mora

Pat Mora

1942-

Pat Mora (born January 19, 1942) is a Hispanic author known primarily for her poetry and children’s books. She was born in El Paso, Texas.

The author of more than 40 volumes of poetry, nonfiction and children’s picture books, Mora has received numerous honors for her work, including an National Endowment of the Arts poetry fellowship, the Civitella Ranieri fellowship, four Southwest Book Awards, the Premio Aztlan Literature Award, the Ohioana Award and the Pellicer-Frost 1999 Bi-National Poetry Award. She has also served as a consultant on U.S.-Mexico youth program exchanges, a museum and university administrator and a teacher of English language arts at all academic levels.

Mora is a popular national speaker shaped by the U.S.-Mexico border, where she was born and spent much of her life. She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pat_Mora

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Hannah More

Hannah More

1745-1833

Hannah More (February 2, 1745-September 7, 1833) was an English religious writer and philanthropist. She can be said to have made three reputations in the course of her long life: As a clever verse-writer and witty talker in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick; as a writer on moral and religious subjects; and as a practical philanthropist.

Born in 1745 at Fishponds in the parish of Stapleton, near Bristol, More was the fourth of five daughters of Jacob More who, though from a Presbyterian family in Norfolk, had become a member of the Church of England, a strong Tory and a schoolmaster at Stapleton in Gloucestershire. In 1756, Hannah More’s eldest sister, Mary, established a boarding school at 6 Trinity Street in Bristol which, after a few years, was moved to Park Street. More became a pupil when she was 12 years old and taught there in her early adulthood.

More’s first literary efforts were pastoral plays, suitable for young ladies to act, the first being written in 1762 under the title of The Search after Happiness; by the mid-1780s, more than 10,000 copies had been sold. Metastasio was one of her literary models; on his opera of Attilio Regulo she based a drama, The Inflexible Captive.

In 1767, More gave up her share in the school after becoming engaged to William Turner of Wraxall, Somerset. The wedding never took place, however, and after much reluctance Hannah More was induced to accept a £200 annuity from Turner. This set her free for literary pursuits and, in the winter of 1773-74, she went to London.

Another drama, The Fatal Falsehood, produced in 1779, was less successful. She published Sacred Dramas in 1782 and it rapidly ran through 19 editions. These and the poems “Bas-Bleu” and “Florio” (1786) mark her gradual transition to more serious views of life, which were fully expressed in prose in Thoughts on the Importance of the Manners of the Great to General Society (1788) and An Estimate of the Religion of the Fashionable World (1790). She was for many years a friend of Beilby Porteus, Bishop of London and a leading abolitionist, who drew her into the group of prominent campaigners against the slave trade.

In 1785, she bought a house at Cowslip Green, near Wrington in northern Somerset, where she settled down to country life with her sister, Martha, and wrote many ethical books and tracts: Strictures on Female Education (1799), Hints towards Forming the Character of a Young Princess (1805), Coelebs in Search of a Wife (only nominally a story, 1809), Practical Piety (1811), Christian Morals (1813), Character of St. Paul (1815) and Moral Sketches (1819). She wrote many spirited rhymes and prose tales, the earliest of which was Village Politics, by Will Chip (1792).

She spent the last five years of her life in Clifton and died on September 7, 1833. She is buried at Church of All Saints, Wrington.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_More

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More

1477-1535

Thomas More was born in Milk Street, London, on February 7, 1478, son of Sir John More, a prominent judge. He was educated at St. Anthony’s School in London. As a youth, he served as a page in the household of Archbishop Morton, who anticipated More would become a “marvelous man.” More went on to study at Oxford. During this time, he wrote comedies and studied Greek and Latin literature. One of his first works was an English translation of a Latin biography of the Italian humanist, Pico della Mirandola. It was printed in 1510.

Around 1494, More returned to London to study law was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1496. He became a barrister in 1501 but did not automatically follow in his father’s footsteps. He was torn between a monastic calling and a life of civil service. While at Lincoln’s Inn, he determined to become a monk and subjected himself to the discipline of the Carthusians, living at a nearby monastery and taking part in the monastic life. The prayer, fasting and penance habits stayed with him for the rest of his life. More’s desire for monasticism was finally overcome by his sense of duty to serve his country in the field of politics. He entered Parliament in 1504 and married for the first time in 1504 or 1505.

More became a close friend with Desiderius Erasmus during the latter’s first visit to England in 1499. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship and correspondence. They produced Latin translations of Lucian’s works, printed at Paris in 1506, during Erasmus’ second visit.

In 1510, he was appointed one of the two undersheriffs of London. In this capacity, he gained a reputation for being impartial and a patron to the poor. In 1511, More’s first wife died in childbirth. More was soon married again to Dame Alice.

During the next decade, More attracted the attention of King Henry VIII. In 1515, he accompanied a delegation to Flanders to help clear disputes about the wool trade. In 1518, he became a member of the Privy Council and was knighted in 1521.

More helped Henry VIII in writing his Defence of the Seven Sacraments, a repudiation of Luther, and wrote an answer to Luther’s reply under a pseudonym. Because of the king’s favor, he was made Speaker of the House of Commons in 1523 and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in 1525. As Speaker, More helped establish the parliamentary privilege of free speech. He refused to endorse King Henry VIII’s plan to divorce Katherine of Aragon (1527). Nevertheless, after the fall of Thomas Wolsey in 1529, More became Lord Chancellor, the first layman yet to hold the post.

He resigned in 1532, citing ill health, but the reason was probably his disapproval of Henry’s stance toward the church. In April 1534, More refused to swear to the Act of Succession and the Oath of Supremacy and was committed to the Tower of London on April 17. More was found guilty of treason and was beheaded alongside Bishop John Fisher on July 6, 1535.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/morebio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Edwin Morgan

Edwin Morgan

1920-2010

Edwin George Morgan (April 27, 1920-August 17, 2010) was a Scottish poet and translator who was associated with the Scottish Renaissance. In 1999, Morgan was made the first Glasgow Poet Laureate. In 2004, he was named as the first Scottish national poet: the Scots Makar.

Morgan was born in Glasgow and grew up in Rutherglen. Morgan entered the University of Glasgow in 1937. It was at university that he studied French and Russian, while self-educating in “a good bit of Italian and German” as well. After interrupting his studies to serve in World War II as a noncombatant conscientious objector with the Royal Army Medical Corps, Morgan graduated in 1947 and became a lecturer at the university. He worked there until his retirement in 1980.

Morgan first outlined his sexuality in Nothing Not Giving Messages: Reflections on His Work and Life (1990). He had written many famous love poems, among them “Strawberries” and “The Unspoken,” in which the love object was not gendered; this was partly because of legal problems at the time but also out of a desire to universalize them.

In 2002, he became the patron of Our Story Scotland. At the Opening of the Scottish Parliament building in Edinburgh on October 9, 2004, Liz Lochhead read a poem written especially for the occasion by Morgan, “Poem for the Opening of the Scottish Parliament.” She was announced as Morgan’s successor as Scots Makar in January 2011.

Near the end of his life, Morgan reached a new audience after collaborating with the Scottish band Idlewild on their album, The Remote Part. In the closing moments of the album’s final track, “In Remote Part/ Scottish Fiction,” he recites a poem, “Scottish Fiction,” written specifically for the song.

In 2007, Morgan contributed two poems to the compilation Ballads of the Book, for which a range of Scottish writers created poems to be made into songs by Scottish musicians. Morgan’s songs, “The Good Years” and “The Weight of Years,” were performed by Karine Polwart and Idlewild, respectively.

In later life, Morgan was cared for at a residential home as his illness worsened. He published a collection in April 2010, Dreams and Other Nightmares, months before his death to mark his 90th birthday.

On August 17, 2010, Edwin Morgan died of pneumonia in Glasgow, Scotland, at the age of 90 years.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Morgan_%28poet%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison

1931-2019

Toni Morrison (born Chloe Anthony Wofford; February 18, 1931-August 5, 2019) was a Nobel Prize- and Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist, editor and professor. Her novels are known for their epic themes, vivid dialogue and richly detailed characters. Among her best-known novels are The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon and Beloved. She also was commissioned to write the libretto for a new opera, Margaret Garner, first performed in 2005.

Morrison was born in Lorain, Ohio, to Ramah (nee Willis) and George Wofford. In 1949, Morrison entered Howard University, where she received a B.A. in English in 1953. She earned a Master of Arts degree in English from Cornell University in 1955. After graduation, Morrison became an English instructor at Texas Southern University in Houston, Texas (1955-57), then returned to Howard to teach English. She became a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority.

In 1966, she went to work as an editor at the New York City headquarters of Random House. As an editor, Morrison played a vital role in bringing black literature into the mainstream, editing books by authors such as Toni Cade Bambara, Angela Davis and Gayl Jones.

Morrison began writing fiction as part of an informal group of poets and writers at Howard who met to discuss their work. She went to one meeting with a short story about a black girl who longed to have blue eyes. She later developed the story as her first novel, The Bluest Eye (1970). In 1975, her novel, Sula (1973), was nominated for the National Book Award. Her third novel, Song of Solomon (1977), brought her national attention and won the National Book Critics Circle Award.

In 1987, Morrison’s novel, Beloved, became a critical success. It won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the American Book Award. That same year, Morrison took a visiting professorship at Bard College.

Morrison was honored with the 1996 National Book Foundation’s Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, which is awarded to a writer “who has enriched our literary heritage over a life of service, or a corpus of work.”

In addition to her novels, Morrison also co-wrote books for children with her younger son, Slade Morrison, who worked as a painter and musician. Slade died on December 22, 2010, aged 45.

Morrison died at Montefiore Medical Center in The Bronx, New York City, on August 5, 2019, from complications of pneumonia. She was 88 years old.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toni_Morrison

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Greg Mortenson

Greg Mortenson

1957-

Greg Mortenson (born December 27, 1957) is an American humanitarian, professional speaker, writer and former mountaineer. He is the co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit Central Asia Institute, as well as the founder of the educational charity, Pennies for Peace. Mortenson is the co-author of The New York Times bestseller, Three Cups of Tea, and author of Stones into Schools: Promoting Peace with Books, Not Bombs, in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Mortenson was born to Lutheran missionary parents in St. Cloud, Minnesota. Through the leadership of the Lutheran Church, Mortenson’s father, Irvin (“Dempsey”), was a fundraiser and development director of the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Tanzania’s first teaching hospital. Mortenson’s mother, Jerene, was the founding principal of International School Moshi.

Mortenson spent his early childhood and adolescence in Tanzania, East Africa, where he learned to speak Swahili fluently. In the early 1970s, when he was 15 years old, Mortenson and his family left Tanzania and moved back to Minnesota. He attended Ramsey High School in Roseville, Minnesota, from 1973 to 1975. After high school, Mortenson served in the U.S. Army in Germany from 1975 to 1977 as a medic and was awarded the Army Commendation Medal. Following his discharge, he attended Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, from 1977 to 1979 on an athletic (football) scholarship. Mortenson graduated from the University of South Dakota in 1993 with a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies and an associate’s degree in nursing.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greg_Mortenson

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Morton

Thomas Morton

1598-1647

Thomas Morton, a trader and lawyer, emigrated from England to the Plymouth Colony in the company of a Captain Wollaston in 1624.

Unable to get along with the Pilgrim authorities, Wollaston, Morton and other settlers established their own small colony of Mount Wollaston at the present-day site of Quincy, Massachusetts. Then most of that community departed with the captain in 1626 in the hope of finding more hospitable surroundings in Virginia. Morton remained behind and renamed the village Mare Mount (Merry Mount), a clear indication of his priorities.

Plymouth leaders did not welcome other settlements in their vicinity, particularly those that openly offended Pilgrim religious sensibilities. One event in particular brought tensions to the boiling point; it was later described by Morton in his own history of the settlement.

In 1628, Plymouth authorities dispatched Myles Standish to deal with their troublesome neighbor. Morton and his associates were too drunk to resist; he was taken into custody and exiled to a small nearby island to await transportation back to England. There, he was supplied with provisions by sympathetic Indians and managed to escape on his own and return to England. He reappeared in Plymouth the following year and promptly ran into difficulties with the officials. His property was confiscated and he was again sent home.

While in England, Morton worked in support of those forces that were attempting to revoke the Plymouth charter. He also wrote his sometimes-comic account of his adventures in New England, lampooning the claustrophobic environments of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay.

Demonstrating lifelong persistence, Morton returned to Massachusetts in 1643 and was promptly imprisoned in Boston. Following his release, he was exiled to Maine, where he remained for the rest of his life.

The harsh reaction of the Pilgrims to Morton was explained only in part by their abhorrence of the Maypole incident. They also were offended by his open ridicule of their society and his practice of conducting Anglican services at Merry Mount. Perhaps of even greater concern was the fact that Morton traded firearms for furs with the local Indians – a practice that the Pilgrims believed was their exclusive preserve.

Source: http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h576.html

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Walter Mosley

Walter Mosley

1952-

Walter Ellis Mosley (born January 12, 1952) is an American novelist, most widely recognized for his crime fiction.

Mosley was born in Watts, Los Angeles, California. His mother, Ella (nee Slatkin), was Polish-Jewish and worked as a personnel clerk; his father, Leroy Mosley (1924-2005), was an African-American from Louisiana who was a supervising custodian at a Los Angeles public school.

For $9.50 a week, Mosley attended the Victory Baptist day school, a private African-American elementary school that conducting pioneering classes in Black history. When he was 12, his parents moved from South Central to more comfortably affluent, working-class west Los Angeles. Mosley attended and then dropped out of Goddard College, a liberal arts college in Plainfield, Vermont, and then earned a political science degree at another college. Abandoning a doctorate in political theory, he started work in computers. While working for Mobil Oil, Mosley took a writing course at City College in Harlem. He still resides in New York City.

Mosley started writing at 34 and has written every day since, penning more than 33 books in a variety of categories, including mystery fiction, other non-mystery fiction, afro-futurist science fiction and nonfiction politics, often publishing two books a year.

Two of his books have been made into films or television specials. His first published book, Devil in a Blue Dress, was the basis of a 1995 movie. The world premiere of his first play, The Fall of Heaven, was staged at the Playhouse in the Park, Cincinnati, Ohio, in January, 2010.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Mosley

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thylias Moss

Thylias Moss

1954-

Thylias Moss (born February 27, 1954, in Cleveland, Ohio) is an American poet, writer, experimental filmmaker, sound artist and playwright of African-American, Indian and European heritage who has published a number of poetry collections, children’s books, essays and multimedia work she calls “poams,” products of acts of making, related to her work in Limited Fork Theory. Among her awards are a MacArthur Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Artist’s Fellowship from the Massachusetts Arts Council, an NEA Grant and the Witter Bynner Award for poetry.

Moss was born Rebecca Brasier in a working-class family in Ohio. Her father was a tire recapper and her mother a maid. She attended Syracuse University and, after several years of working, she enrolled in Oberlin College in 1979 and graduated in 1981. Moss later received a Master of Arts in English, with an emphasis on writing, from the University of New Hampshire.

Moss is now Professor of English and Professor of Art and Design at the University of Michigan. She lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thylias_Moss

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Mourning Dove

Mourning Dove

1888-1936

Mourning Dove was a Native American author best known for her 1927 novel, Cogewea, the Half-Blood: A Depiction of the Great Montana Cattle Range, which tells the story of Cogewea, a mixed-blood ranch woman on the Flathead Indian Reservation. The novel is one of the first written by a Native American woman and one of few early Native American works with a female central character. She is also known for Coyote Stories (1933), a collection of Native American folklore.

Mourning Dove is the English translation of her Indian name, Hum-isha-ma; her English name was Christal Quintasket. She was born in 1888 near Bonners Ferry, Idaho, to a Colville mother and a half-Okanagan, half-Irish father. She died on August 8, 1936.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mourning_Dove_%28author%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Anna Cora Mowatt

Anna Cora Mowatt

1819-1870

Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie was an author, playwright, public reader and actress. She was born in Bordeaux, France, on March 5, 1819. Her father was Samuel Gouveneur Ogden. Her mother was Eliza Lewis Ogden, the granddaughter of Francis Lewis, a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence. In 1826, when Anna was six years old, the Ogden family returned to the United States.

On October 6, 1834, 14-year-old Ogden eloped with James Mowatt (1805-1849), a lawyer and her teacher. They moved to an estate in Flatbush, New York. After her marriage, she continued with her games of hoop rolling and skipping rope, though her husband made sure she continued her studies.

Mowatt’s first book, Pelayo, or the Cavern of Covadonga, was published in 1836, then Reviewers Reviewed in 1837, using the pseudonym “Isabel.” She wrote articles that were in The Ladies’ Companion and Sargent’s Magazine. She wrote a six-act play, Gulzara, published in The New World. Under the pseudonym Henry C. Browning, she wrote a biography of Goethe. Using the pseudonym “Helen Berkley,” she wrote two novels: The Fortune Hunter and Evelyn. In 1841, due to financial problems, Mowatt became a public reader. Her readings were popular and well attended, but her career as a reader was short-lived due to respiratory problems. While recovering from her illness, she returned to her writing.

In 1845, her best-known work, the play Fashion, was published. It received rave reviews and opened at the Park Theatre, New York, on March 24, 1845. On June 13, 1845, she made another career move to acting and debuted with great success at the Park Theatre as Pauline in The Lady of Lyons. Although her next play, Armand, the Child of the People, was published in 1847 and also received good reviews, she continued her acting career. She performed leading roles in Shakespeare, melodramas and her own plays. She toured the United States and Europe for the next eight years.

On February 15, 1851, her husband died. After a short break, she resumed her acting career. In December 1853, her book, Autobiography of an Actress, was published. Mowatt’s last appearance on the public stage was June 3, 1854.

On June 7, 1853, Mowatt married William Foushee Ritchie. During the next few years, she wrote two more novels: Mimic Life, published in 1855, and Twin Roses, published in 1857. She left her husband in 1860 and moved to Europe, where she wrote the novel, Mute Singer, published in 1861, and Fairy Fingers, published in 1865. Later that year, she moved to England, where she wrote The Clergyman’s Wife and Other Sketches in 1867.

Anna Cora Ogden Mowatt Ritchie died in Twickenham, England, on July 21, 1870.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Cora_Mowatt

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Bharati Mukherjee

Bharati Mukherjee

1940-2017

Bharati Mukherjee (July 27, 1940-January 28, 2017) was an award-winning, Indian-born American writer and professor emerita in the department of English at the University of California, Berkeley.

Of Bengali origin, Mukherjee was born in Calcutta (now called Kolkata), West Bengal, India. She later travelled with her parents to Europe after Independence, only returning to Calcutta in the early 1950s. There, she attended the Loreto School. She received her B.A. from the University of Calcutta in 1959 as a student of Loreto College and subsequently earned her M.A. from the University of Baroda in 1961. She next travelled to the United States to study at the University of Iowa. She received her M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1963 and her Ph.D in 1969 from the department of Comparative Literature.

After more than a decade living in Montreal and Toronto in Canada, Mukherjee and her husband, Clark Blaise, returned to the United States. She wrote of the decision in “An Invisible Woman,” published in a 1981 issue of Saturday Night. Mukherjee and Blaise co-authored Days and Nights in Calcutta (1977). They also wrote the 1987 work, The Sorrow and the Terror: The Haunting Legacy of the Air India Tragedy (Air India Flight 182).

In addition to writing numerous works of fiction and nonfiction, Mukherjee taught at McGill University, Skidmore College, Queens College and City University of New York before joining Berkeley.

Mukherjee died due to complications of rheumatoid arthritis and takotsubo cardiomyopathy on January 28, 2017 in Manhattan at the age of 76.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bharati_Mukherjee

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Anthony Munday

Anthony Munday

1560-1633

Anthony Munday (or Monday), English dramatist and miscellaneous writer, was the son of Christopher Monday, a London draper. He had already appeared on the stage when, in 1576, he bound himself as an apprentice for eight years to John Allde, a stationer, an engagement from which he was speedily released because, in 1578, he was in Rome.

In the opening lines of his English Romayne Lyfe (1582), he avers that in going abroad he was actuated solely by a desire to see strange countries and to learn foreign languages; but he must be regarded, if not as a spy sent to report on the English Jesuit College in Rome, as a journalist who meant to make literary capital out of the designs of the English Catholics resident in France and Italy.

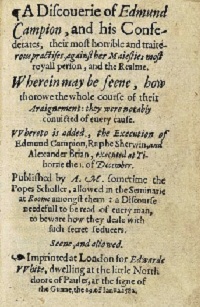

He returned to England in 1578-1579 and became an actor again, being a member of the Earl of Oxford’s company between 1579 and 1584. In a Catholic tract entitled “A True Reporte of the death of M. Campion” (1581), Munday is accused of having deceived his master, Allde – a charge he refuted by publishing Allde’s signed declaration to the contrary – and is also said to have been hissed off the stage. He was one of the chief witnesses against Edmund Campion and his associates and wrote, at about this time, five anti-popish pamphlets, among them the savage and bigoted tract entitled “A Discoverie of Edmund Campion and his Confederates whereto is added the execution of Edmund Campion, Raphe Sherwin, and Alexander Brian,” the first part of which was read aloud from the scaffold at Campion’s death in December 1581. His political services against the Catholics were rewarded in 1584 by the post of messenger to her Majesty’s chamber, and from this time he seems to have ceased to appear on the stage.

In 1598-1599, he devoted himself to writing for the booksellers and the theatres, compiling religious works, translating Amadis de Gaule and other French romances and putting words to popular airs. He was the chief pageant-writer for London from 1605 to 1616 and it is likely that he supplied most of the pageants between 1592 and 1605, of which no authentic record has been kept. It is by these entertainments of his, which rivaled in success those of Ben Jonson and Middleton, that he won his greatest fame.

Of the 18 plays between the dates of 1584 and 1602 that are assigned to Munday in collaboration with Henry Chettle, Michael Drayton, Thomas Dekker and other dramatists, only four are extant.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/mundaybio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Alice Munro

Alice Munro

1931-2024

Alice Ann Munro (nee Laidlaw; born July 10, 1931-13 May 2024) was a Canadian short story writer, the winner of the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work, a three-time winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Award for fiction and a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize. Munro wrote about the human condition and relationships seen through the lens of daily life.

Munro was born in the town of Wingham, Ontario, into a family of fox and poultry farmers. Her father was Robert Eric Laidlaw and her mother, a schoolteacher, was Anne Clarke Laidlaw (nee Chamney). She began writing as a teenager and published her first story, “The Dimensions of a Shadow,” in 1950 while a student at the University of Western Ontario. During this period, she worked as a waitress, a tobacco picker and a library clerk. In 1951, she left the university, where she had been majoring in English since 1949, to marry James Munro and move to Vancouver, British Columbia.

In 1963, the Munros moved to Victoria, where they opened Munro’s Books, a popular bookstore still in business. Alice and James Munro were divorced in 1972. She returned to Ontario to become Writer-in-Residence at the University of Western Ontario. In 1976, she married Gerald Fremlin, a geographer. The couple moved to a farm outside Clinton, Ontario.

Munro’s first collection of stories, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), was highly acclaimed and won that year’s Governor General’s Award, Canada’s highest literary prize. That success was followed by Lives of Girls and Women (1971), a collection of interlinked stories published as a novel. In 1978, Munro published another collection of interlinked stories, Who Do You Think You Are? Through the 1980s and 1990s, Munro published a short story collection about once every four years to increasing acclaim, winning both national and international awards.

Munro’s stories frequently appear in publications such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Grand Street, Mademoiselle and The Paris Review. Her latest collection, Too Much Happiness, was published in August 2009.