Author Biographies 12

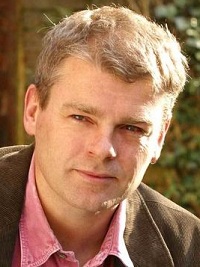

Mark Haddon

Mark Haddon

1962-

Mark Haddon (born October 28, 1962) is an English novelist and poet, best known for his 2003 novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.

Haddon was born in 1962 in Northampton and educated at Uppingham School and Merton College, Oxford, where he studied English language. Afterward, he was employed in several different occupations. One included working with people and children with disabilities, and another included creating illustrations and cartoons for magazines and newspapers. He lived in Boston for a year with his wife until they moved back to England. He then took up painting and selling abstract art.

In 1987, Haddon wrote his first children’s book, Gilbert’s Gobstopper. This was followed by many other children’s books, which were often self-illustrated.

In 2003, Haddon won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award and, in 2004, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize Overall Best First Book for his novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. His second adult novel, A Spot of Bother, was published in September 2006.

Haddon is also known for his series of Agent Z books, one of which, Agent Z and the Penguin from Mars, was made into a 1996 Children’s BBC sitcom. He also wrote the screenplay for the BBC television adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ story, Fungus the Bogeyman, screened on BBC1 in 2004. In 2007, he wrote the BBC television drama, Coming Down the Mountain.

In 2009, he donated the short story, “The Island,” to Oxfam’s Ox-Tales project, four collections of UK stories written by 38 authors. Haddon’s story was published in the Fire collection.

Haddon lives in Oxford.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Haddon

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Jessica Hagedorn

Jessica Hagedorn

1949-

Jessica Tarahata Hagedorn (born 1949) is a Filipino-American playwright, writer, poet, storyteller, musician and multimedia performance artist.

Hagedorn was born in Manila to a Scots-Irish-French-Filipino mother and a Filipino-Spanish father with one Chinese ancestor. Moving to San Francisco in 1963, Hagedorn received her education at the American Conservatory Theater training program. To further pursue playwriting and music, she moved to New York in 1978.

Joseph Papp produced her first play, Mango Tango, in 1978. Hagedorn’s other productions include: Tenement Lover, Holy Food and Teenytown. Her mixed-media style often incorporates song, poetry, images and spoken dialogue.

In 1985, 1986 and 1988, she received MacDowell Colony fellowships, which helped enable her to write the novel, Dogeaters, illuminating many different aspects of Filipino experience and focusing on the influence of America through radio, television and movies. She shows the complexities of the love-hate relationship many Filipinos in diaspora feel toward their past. After its publication in 1990, her novel earned a 1990 National Book Award nomination and an American Book Award. In 1998, La Jolla Playhouse produced a stage adaptation.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jessica_Hagedorn

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

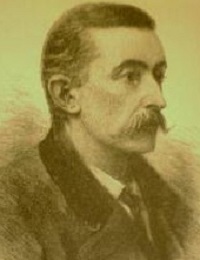

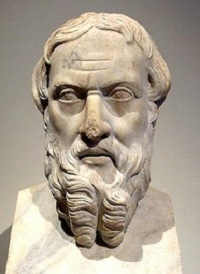

H. Rider Haggard

H. Rider Haggard

1856-1925

Sir Henry Rider Haggard (June 22, 1856-May 14, 1925) was an English writer of adventure novels set in exotic locations, predominantly Africa, and a founder of the Lost World literary genre. He was also involved in agricultural reform around the British Empire.

Haggard was born at Bradenham, Norfolk, the eighth of 10 children, to Sir William Meybohm Rider Haggard, a barrister, and Ella Doveton, an author and poet. In 1875, Haggard’s father sent him to what is now South Africa to take up an unpaid position as assistant to the secretary to Sir Henry Bulwer, Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Natal. In 1876, he was transferred to the staff of Sir Theophilus Shepstone, Special Commissioner for the Transvaal. It was in this role that Haggard was present in Pretoria in April 1877 for the official announcement of the British annexation of the Boer Republic of the Transvaal. Indeed, Haggard raised the Union flag and read out much of the proclamation following the loss of voice of the official originally entrusted with the duty.

Moving back to England in 1882, he settled in Ditchingham, Norfolk. Haggard turned to the study of law and was called to the bar in 1884. His practice of law was desultory, however, and much of his time was taken up by the writing of novels, which he saw as being more profitable.

Haggard lived at 69 Gunterstone Road in Hammersmith, London, from mid-1885 to about April 1888. It was at this address that he completed King Solomon’s Mines (1885). Heavily influenced by the larger-than-life adventurers he met in Colonial Africa (most notably Frederick Selous and Frederick Russell Burnham), the great mineral wealth discovered in Africa and the ruins of ancient lost civilizations of the continent, such as Great Zimbabwe, Haggard created his Allan Quatermain adventures. Three of his books are: The Wizard (1896); Elissa, the Doom of Zimbabwe (1899); and Black Heart and White Heart: A Zulu Idyll (1900).

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._Rider_Haggard

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

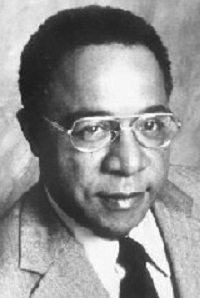

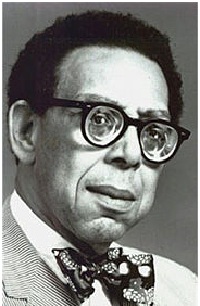

Alex Haley

Alex Haley

1921-1992

Alexander Murray Palmer Haley (August 11, 1921-February 10, 1992) was an African-American writer. He is best known as the author of Roots: The Saga of an American Family and the coauthor of The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Haley was born in Ithaca, New York, the oldest of three brothers and a sister. Haley lived in Henning, Tennessee, before his family returned to Ithaca when he was five years old. Haley was enrolled at Alcorn State University at age 15. Two years later he returned to his parents to inform them of his withdrawal from college. His father, Simon Haley, felt that Alex needed discipline and growth and convinced his son to enlist in the military when he turned 18. On May 24, 1939, Haley began his 20-year enlistment with the U.S. Coast Guard.

After World War II, Haley was able to petition the Coast Guard to allow him to transfer into the field of journalism and, by 1949, he had become a Petty Officer First Class in the rating of Journalist. He later advanced to Chief Petty Officer and held this grade until his retirement from the Coast Guard in 1959.

After his retirement, Haley began his writing career and eventually became a senior editor for Reader’s Digest.

Haley died in Seattle, Washington, of a heart attack and was buried beside his childhood home in Henning, Tennessee.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alex_Haley

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

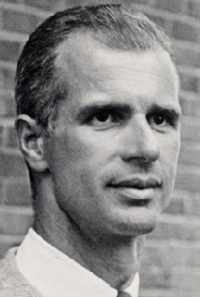

Donald Hall

Donald Hall

1928-2018

Donald Hall was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1928. He began writing as an adolescent and attended the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference at the age of 16 – the same year he had his first work published. He earned a B.A. from Harvard in 1951 and a B. Litt. from Oxford in 1953.

Hall has published numerous books of poetry, most recently White Apples and the Taste of Stone: Selected Poems 1946-2006; The Painted Bed (2002); and Without: Poems (1998), which was published on the third anniversary of his wife and fellow poet Jane Kenyon’s death from leukemia. Other notable collections include: The One Day (1988), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Los Angeles Times Book Prize and a Pulitzer Prize nomination; The Happy Man (1986), which won the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize; and Exiles and Marriages (1955), which was the Academy’s Lamont Poetry Selection for 1956.

Besides poetry, Hall has written books about baseball, the sculptor Henry Moore and the poet Marianne Moore. He is also the author of children’s books, including: Ox-Cart Man (1979), which won the Caldecott Medal; short stories, including Willow Temple: New and Selected Stories (2003); and plays. He has also published several autobiographical works, such as The Best Day, the Worst Day: Life with Jane Kenyon (2005) and Life Work (1993), which won the New England Book Award for nonfiction.

Hall has edited more than two dozen textbooks and anthologies, including The Oxford Book of Children’s Verse in America (1990), The Oxford Book of American Literary Anecdotes (1981), New Poets of England and America (with Robert Pack and Louis Simpson, 1957) and Contemporary American Poetry (1962; revised 1972). He served as poetry editor of The Paris Review from 1953 to 1962 and as a member of editorial board for poetry at Wesleyan University Press from 1958 to 1964.

His honors include two Guggenheim fellowships, the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Silver medal, a Lifetime Achievement award from the New Hampshire Writers and Publisher Project and the Ruth Lilly Prize for poetry. Hall also served as Poet Laureate of New Hampshire from 1984 to 1989.

Hall died on June 23, 2018, in Wilmot, New Hampshire.

Source: http://www.poets.org/poet.php/prmPID/264

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Joseph Hall

Joseph Hall

1574-1656

Joseph Hall was born at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, son of John Hall and Winifred Bambridge. He was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he was part of the University Wits. He published his Virgidemiarum, six books of “toothless satires,” in 1597 and 1598. These verse satires were, along with those of his friend John Donne, the first English satires that followed classical models. Hall proclaimed himself to be the first English satirist, thus offending John Marston, who duly attacked Hall in his own satires of 1598. Hall’s satires were decidedly juvenile and their fallacies were later expounded upon by Milton. In 1599, the Archbishop of Canterbury ordered Hall’s satires to be burned alongside those of Marston, Marlowe and Sir John Davies, but the order was not carried out.

Hall had taken holy orders and, in 1601, took residence in Halsted, Essex. He married in 1603, after which he traveled extensively in the Netherlands and on the continent. He published a prose satire, Mundus alter et idem, in 1605; it was translated into English by J. Healey in 1609. Hall also published religious writings, notably Meditations and Vows (1605) and Characters of Virtues and Vices (1608). Hall was appointed chaplain to Prince Henry in 1608 and was made Dean of Worcester by James I, representing the king at the Synod of Dort. Hall was later made Bishop of Exeter in 1627 and of Norwich in 1641.

In 1641, Hall published Episcopacy by Divine Right, Asserted by J.H., an attack against Smectymnuus (1641), a pamphlet against episcopacy. This brought him into conflict with Milton, who defended the same. In 1642, Hall was among 13 bishops imprisoned by Parliament, his cathedral was desecrated in the Civil War and Hall himself was evicted from his palace in 1647. He retired to the village of Higham and continued writing until his death. Reduced to beggary, Hall nonetheless survived until 1656. His last works were: Observations on some Specialities of Divine Providence and Hard Measure (1674). He was attended in his final days by his good friend, Sir Thomas Browne, who venerated him.

After a long infirmity, Hall died on September 8, 1656.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/hall/hallbio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

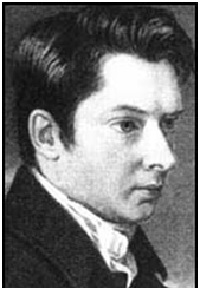

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

1755-1804

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755-July 12, 1804) was a Founding Father, soldier, economist, political philosopher, one of America’s first constitutional lawyers and the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton was the primary author of the economic policies of the George Washington Administration, especially the funding of state debts by the Federal government, the establishment of a national bank, a system of tariffs and friendly trade relations with Britain. He became the leader of the Federalist Party, created largely in support of his views, and was opposed by the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Hamilton served in the American Revolutionary War. At the start of the war, he organized an artillery company and was chosen as its captain. He later became the senior aide-de-camp and confidant to General George Washington, the American commander-in-chief. He served again under Washington in the army raised to defeat the Whiskey Rebellion, a tax revolt of western farmers in 1794. In 1798, Hamilton called for mobilization against France after the XYZ Affair and secured an appointment as commander of a new army, which he trained. However, the Quasi-War, although hard-fought at sea, was never officially declared. In the end, President John Adams found a diplomatic solution that avoided war.

Of illegitimate birth and raised in the West Indies, Hamilton was effectively orphaned at about the age of 11. Recognized for his abilities and talent, he came to North America for his education, sponsored by people from his community. He attended King’s College (now Columbia University). After the American Revolutionary War, Hamilton was elected to the Continental Congress from New York. He resigned to practice law and founded the Bank of New York.

Hamilton was among those dissatisfied with the first national governance document, the Articles of Confederation. While serving in the New York Legislature, Hamilton was sent as a delegate to the Annapolis Convention in 1786 to revise the Articles, but it resulted instead in a call for a new constitution. He was one of New York’s delegates at the Philadelphia Convention that drafted the new constitution in 1787 and was the only New Yorker who signed it. In support of ratification by the states for the new Constitution, Hamilton wrote many of the Federalist Papers, still an important source for Constitutional interpretation. In the new government under President George Washington, he was appointed Secretary of the Treasury. An admirer of British political systems, Hamilton was a nationalist who emphasized strong central government and successfully argued that the implied powers of the Constitution could be used to fund the national debt, assume state debts and create the government-owned Bank of the United States. These programs were funded primarily by a tariff on imports and later also by a highly controversial excise tax on whiskey.

Embarrassed when an extramarital affair with Maria Reynolds became public, Hamilton resigned from office in 1795 and returned to the practice of law in New York. However, he kept his hand in politics and was a powerful influence on the cabinet of President Adams (1797-1801). Hamilton’s opposition to John Adams helped cause Adams’ defeat in the 1800 elections. When Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in the electoral college, Hamilton helped defeat his bitter personal enemy Burr and elect Jefferson as president. After opposing Adams, the candidate of his own party, Hamilton was left with few political friends. In 1804, as the next presidential election approached, Hamilton again opposed the candidacy of Burr. Taking offense at some of Hamilton’s comments, Burr challenged him to a duel and mortally wounded Hamilton, who died within days.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Hamilton

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Edith Hamilton

Edith Hamilton

1868-1963

Edith Hamilton (August 12, 1867-May 31, 1963) was an American educator and author who was recognized as “the greatest woman Classicist.” She was 62 years old when The Greek Way, her first book, was published in 1930. It was instantly successful and is the earliest expression of her belief in “the calm lucidity of the Greek mind” and “that the great thinkers of Athens were unsurpassed in their mastery of truth and enlightenment.”

In 1957, when the Book-of-the-Month Club selected The Greek Way (1930) as a featured book, it enhanced her efforts at directing the American mind toward ancient Greece, despite it having been published 27 years earlier. Moreover, by then, she already had published other books, among them The Roman Way (1932), Mythology (1942) and The Echo of Greece (1957); to date, at the high school and university levels, Mythology remains the premier introductory text about its subject. The New York Times has described her as the Classical Scholar who “brought into clear and brilliant focus the Golden Age of Greek life and thought … with Homeric power and simplicity in her style of writing.”

She died in Washington, D.C., on May 31, 1963, at the age of 95.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Hamilton

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Elizabeth Hamilton

Elizabeth Hamilton

1756?-1816

Elizabeth Hamilton (July 25, 1756?-1816) was a British essayist, poet, satirist and novelist. Born in Belfast to Charles Hamilton (d. 1759), a Scottish merchant, and his wife Katherine Mackay (d. 1767), she lived most of her life in Scotland, dying in Harrogate in England after a short illness.

Her first literary efforts were directed in supporting her brother Charles in his orientalist and linguistic studies. After his death in 1792, she continued to publish orientalist scholarship, as well as historical, educationalist and theoretical works. She wrote “The Cottagers of Glenburnie” (1808), a tale that had much popularity in its day, and perhaps had some effect in the improvement of certain aspects of humble domestic life in Scotland. She also wrote the satirical novel, Memoirs of Modern Philosophers (1800), Letters on Education, Essays on the Human Mind and the anti-Jacobin Letters of a Hindoo Rajah (1796), a work in the tradition of Montesquieu and Goldsmith.

Her most important pedagogical works are: Letters on Education, Essays on the Human Mind (1796), Letters on the Elementary Principles of Education (1801), Letters Addressed to the Daughter of a Nobleman, on the Formation of Religious and Moral Principle (1806) and Hints Addressed to the Patrons and Directors of Schools (1815).

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Hamilton

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Patrick Hamilton

Patrick Hamilton

1904-1962

Patrick Hamilton (March 17, 1904-September 23, 1962) was an English playwright and novelist. He was born Anthony Walter Patrick Hamilton in the Sussex village of Hassocks, near Brighton, to writer parents. Due to his father’s alcoholism and financial ineptitude, the family spent much of Hamilton’s childhood living in boarding houses in Chiswick and Hove. His education was patchy and ended just after his 15th birthday, when his mother withdrew him from Westminster School. His first published work was a poem, “Heaven,” in The Poetry Review in 1919.

After a brief career as an actor, he became a novelist in his early 20s with the publication of Monday Morning (1925), written when he was 19. Craven House (1926) and Twopence Coloured (1928) followed, but his first real success was the play, Rope (1929). The Midnight Bell (1929) was later published along with The Siege of Pleasure (1932) and The Plains of Cement (1934) as the semi-autobiographical trilogy, Twenty Thousand Streets under the Sky (1935).

Other works include: Hangover Square (1941); Impromptu in Moribundia (1939); The Slaves of Solitude (1947); Gorse Trilogy (three novels comprised of: The West Pier, 1952; Mr. Stimpson and Mr. Gorse, 1953; Unknown Assailant, 1955).

Hamilton had begun to consume alcohol excessively while still a relatively young man. After a declining career and melancholia, he died in 1962 in Sheringham, Norfolk, of cirrhosis of the liver and kidney failure.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Hamilton_%28writer%29

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Virginia Hamilton

Virginia Hamilton

1936-2002

Virginia Esther Hamilton (March 12, 1936-February 19, 2002) was an award-winning author of children’s books. She wrote 41 books, including M.C. Higgins, the Great, for which she won the National Book Award in 1974 and the 1975 Newbery Medal.

Named for her grandfather’s home state, Hamilton grew up in Yellow Springs, Ohio. She attended Antioch College and then transferred to Ohio State University. She married the poet Arnold Adoff in 1960.

Hamilton’s first book, as a child, was The Novel. Then came Zeely, published in 1967, which won numerous awards, including the Edgar Allan Poe Award, the Coretta Scott King Award, The Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, Tthe Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal and The Hans Christian Andersen Award.

The Virginia Hamilton Conference on Multicultural Literature for Youth has been conducted at Kent State University each year since 1984.

She died of breast cancer in 2002.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Hamilton

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Jupiter Hammon

Jupiter Hammon

1711-1806?

Jupiter Hammon (October 17, 1711-before 1806) was a black poet who in 1761 became the first African-American writer to be published in the present-day United States (in 1773, Phillis Wheatley, also an American slave, had her collection of poems first published in London, England). Additional poems and sermons were also published. Born into slavery, Hammon was never emancipated. He had died by 1806. A devout Christian, he is considered one of the founders of African-American literature.

Hammon was owned by four generations of the Lloyd family of Queens on Long Island, New York. Unlike most slaves, his father, named Opium, had learned to read and write. The Lloyds allowed Hammon to attend school, where he also learned to read and write. As an adult, he worked for them as a domestic servant, clerk, farmhand and artisan in the Lloyd family business. He became a fervent Christian, as were the Lloyds.

His first published poem, “An Evening Thought. Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries: Composed by Jupiter Hammon, a Negro belonging to Mr. Lloyd of Queen’s Village, on Long Island, the 25th of December, 1760,” appeared as a broadside in 1761. He published three other poems and three sermon essays.

Although not emancipated, Hammon participated in new Revolutionary War groups such as the African Society. There, on September 24, 1786, he delivered his “Address to the Negroes of the State of New York,” also known as the “Hammon Address.” He was 76 years old and had spent his lifetime in slavery. He said, “If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being black, or for being slaves.” He also said that, while he personally had no wish to be free, he did wish others, especially “the young Negroes, were free.”

The speech draws heavily on Christian motifs and theology. For example, Hammon said that black people should maintain their high moral standards because being slaves on Earth had already secured their place in Heaven. He promoted gradual emancipation as a way to end slavery. Scholars think perhaps Hammon supported this plan because he believed that immediate emancipation of all slaves would be difficult to achieve. New York Quakers, who supported abolition of slavery, published his speech. It was reprinted by several abolitionist groups, including the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery.

In the two decades after the Revolutionary War and creation of the new government, Northern states generally abolished slavery. In the Upper South, so many slaveholders manumitted slaves that the proportion of free blacks among African-Americans increased from less than one percent in 1790 to more than 10 percent by 1810. In the United States as a whole, by 1810 the number of free blacks was 186,446, or 13.5 percent of all African-Americans.

Hammon’s speech and his poetry are often included in anthologies of notable African-American and early American writing.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_Hammon

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

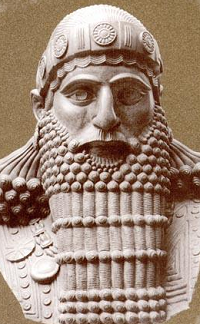

Hammurabi

Hammurabi

1810-1750 BC

Hammurabi (Akkadian from Amorite Ammurapi, “the kinsman is a healer,” from Ammu, “paternal kinsman,” and Rapi, “healer”) (died c. 1750 BC) was the sixth king of Babylon from 1792 BC to 1750 BC, middle chronology. As the first king of the Babylonian Empire following the abdication of his father, he extended Babylon’s control over Mesopotamia by winning a series of wars against neighboring kingdoms. Although his empire controlled all of Mesopotamia at the time of his death, his successors were unable to maintain it.

Hammurabi is known for the set of laws called Hammurabi’s Code, one of the first written codes of law in recorded history. These laws were written on a stone tablet standing more than eight feet tall that was found in 1901. Owing to his reputation in modern times as an ancient lawgiver, Hammurabi’s portrait is in many government buildings throughout the world.

Hammurabi was a First Dynasty king of the city-state of Babylon, and inherited the power from his father, Sin-Muballit, in c. 1792 BC. Babylon was one of the many ancient city-states that dotted the Mesopotamian plain and waged war on each other for control of fertile agricultural land. Though many cultures co-existed in Mesopotamia, Babylonian culture gained a degree of prominence among the literate classes throughout the Middle East.

Vast numbers of contract tablets, dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and his successors, have been discovered, as well as 55 of his own letters. These letters give a glimpse into the daily trials of ruling an empire, from dealing with floods and mandating changes to a flawed calendar, to taking care of Babylon’s massive herds of livestock.

Hammurabi died and passed the reins of the empire on to his son, Samsu-Iluna, in c. 1750 BC.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammurabi

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

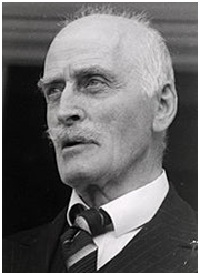

Knut Hamsun

Knut Hamsun

1859-1952

Knut Hamsun (August 4, 1859-February 19, 1952) was a Norwegian author who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1920. He was praised by King Haakon VII of Norway as “Norway’s soul.”

Hamsun’s work spans more than 70 years and shows variation with regard to the subject, perspective and environment. He published more than 20 novels, a collection of poetry, some short stories and plays, a travelogue and some essays.

The young Hamsun objected to realism and naturalism. He argued that the main object of modern literature should be the intricacies of the human mind, that writers should describe the “whisper of blood, and the pleading of bone marrow.” Hamsun is considered the “leader of the Neo-Romantic revolt at the turn of the century,” with works such as Hunger (1890), Mysteries (1892), Pan (1894) and Victoria (1898). His later works – in particular his Nordland novels – were influenced by the Norwegian new realism, portraying everyday life in rural Norway and often employing local dialect, irony and humor. The epic work, Growth of the Soil (1917), earned him the Nobel Prize.

Knut Hamsun died on February 19, 1952, aged 92, in Grimstad, Norway.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knut_Hamsun

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lorraine Hansberry

Lorraine Hansberry

1930-1965

Lorraine Vivian Hansberry (May 19, 1930-January 12, 1965) was an African-American playwright and author of political speeches, letters and essays. Her best-known work, A Raisin in the Sun, was inspired by her family’s battle against racial segregation in Chicago.

Hansberry was the youngest of four children of Carl Augustus Hansberry, a successful real estate broker, and Nannie Louise Perry. She attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison but found college uninspiring and left in 1950 to pursue her career as a writer in New York City, where she attended The New School. She worked on the staff of the black newspaper, Freedom.

A Raisin in the Sun was written at this time and was a huge success. It was the first play written by an African-American woman to be produced on Broadway. While many of her other writings were published in her lifetime – essays, articles and the text for the SNCC book, The Movement – the only other play given a contemporary production was The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window.

After a battle with pancreatic cancer, she died on January 12, 1965, aged 34.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorraine_Hansberry

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy

1840-1928

Thomas Hardy (June 2, 1840-January 11, 1928) was an English novelist and poet. While his works typically belong to the Naturalism movement, several poems display elements of the previous Romantic and Enlightenment periods of literature, such as his fascination with the supernatural.

While he regarded himself primarily as a poet who composed novels for financial gain, he became and continues to be widely regarded for his novels, such as Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Far from the Madding Crowd. Hardy’s poetry, first published in his 50s, has come to be as well regarded as his novels and has had a significant influence on modern English poetry.

Hardy was born at Higher Bockhampton, to the east of Dorchester in Dorset, England. His father, Thomas, worked as a stonemason and local builder. His mother, Jemima, was well-read. His formal education ended at the age of 16 when he became apprenticed to James Hicks, a local architect. Hardy trained as an architect in Dorchester before moving to London in 1862; there, he enrolled as a student at King’s College, London. He won prizes from the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Architectural Association. Hardy never felt at home in London and, five years later, concerned about his health, he returned to Dorset and decided to dedicate himself to writing.

Hardy became ill with pleurisy in December 1927 and died at Max Gate just after 9 p.m. on January 11, 1928, having dictated his final poem to his wife on his deathbed; the cause of death was cited on his death certificate as “cardiac syncope,” with “old age” given as a contributory factor.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hardy

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Thomas Hariot

Thomas Hariot

1560-1621

Thomas Hariot (or Harriot), an eminent mathematician and astronomer, was born at Oxford in 1560. He took his degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1579 and, in 1584, he accompanied Sir Walter Raleigh in his expedition to Virginia, where he was employed in surveying and mapping the country. Upon his return to England in 1588, he published his Report of the New found land of Virginia, the commodities there found to be raised, &c.

Hariot was introduced by Raleigh to the Earl of Northumberland, whose zeal for the promotion of science had led him to maintain several learned men of the day, such as Robert Hues, Walter Warner and Nathaniel Tarporley. This enlightened nobleman received Hariot into his house and settled on him an annual salary of 300 pounds, which he enjoyed to the time of his death in July 1621. His body was interred in St. Christopher’s Church, London. A monument erected to his memory, with the church itself, was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1666.

During his lifetime, Hariot was known to the world merely as an eminent algebraist; but, from a paper by Zach in the “Astronomical Ephemerish” of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Berlin for the year 1788, it appears he was equally deserving of eminence as an astronomer. The paper contains an account of the manuscripts found by Zach at the seat of the Earl of Egremont, to whom they had descended from the Earl of Northumberland. From it we learn: That Hariot carried on a correspondence with Kepler concerning the rainbow; that he had discovered the solar spots prior to any mention having been made of them by Galileo, Scheiner or Phrysius; and that the satellites of Jupiter were observed by him on January 16, 1610, although their first discovery is generally attributed to Galileo, who states that he had observed them on the 7th of that month. A correspondence with Kepler on various optical and other subjects is printed among the letters of Kepler.

Ten years after Hariot’s death his Algebra, Artis Analyticae Praxis, ad Aequationes Algebraicas Nova, Epedita et Generali Methoda Resolvendas was published by his friend, Walter Warner.

Source: http://www.luminarium.org/renlit/haribio.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Joy Harjo

Joy Harjo

1951-

Joy Harjo (born May 9, 1951, in Tulsa, Oklahoma) is a Native American poet, musician and author of ancestry. Known primarily as a poet, Harjo has also taught at the college level, played alto saxophone with a band called Poetic Justice, edited literary journals and written screenplays. She is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and is of Cherokee descent. She is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa.

In 1995, Harjo received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joy_Harjo

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

1825-1911

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825-February 22, 1911) was an African-American abolitionist and poet. Born free in Baltimore, Maryland, she had a long and prolific career, publishing her first book of poetry at 20 and her first novel, the widely praised, Iola Leroy, at age 67.

She was born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland. After her mother died when she was three years old in 1828, she was raised by her aunt and uncle. She was educated at the Academy for Negro Youth, a school run by her uncle, Rev. William Watkins, who was a civil rights activist. At 14, she found work as a seamstress.

Watkins had her first volume of verse, Forest Leaves, published in 1845 (it has been lost). Her second book, Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, published in 1854, was extremely popular. Many African-American women’s service clubs named themselves in her honor and across the nation, in cities such as St. Louis, St. Paul and Pittsburgh, F.E.W. Harper Leagues and Frances E. Harper Women’s Christian Temperance Unions thrived well into the 20th century.

In 1850, Watkins moved to Ohio, where she worked as the first female teacher at Union Seminary, established by the Ohio Conference of the AME Church. In 1853, Watkins joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and became a traveling lecturer for the group. In 1854, Watkins delivered her first anti-slavery speech, “Education and the Elevation of Colored Race.” The success of this speech resulted in a two-year lecture tour in Maine for the Anti-Slavery Society. She traveled, lecturing throughout the East and Midwest, from 1856 to 1860. In 1859, her story, “The Two Offers,” was published in The Anglo-African Magazine, a great accomplishment as it became the first short story to ever be published by an African-American.

In 1860, she married Fenton Harper, a widower with three children. They had a daughter together in 1862. For a time, Frances withdrew from the lecture circuit. However, after her husband died in 1864, Watkins resumed her travels and lecturing.

Harper was a strong supporter of prohibition and woman’s suffrage. She was also active in the Unitarian Church, which supported abolition. She often would read her poetry at the public meetings, including the extremely popular, “Bury Me in a Free Land.” She was connected with national leaders in suffrage and, in 1866, gave a moving speech before the National Women’s Rights Convention, demanding equal rights for all, including black women. From 1883 to 1890, she helped organize activities for the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

She also continued with her writing and publishing poetry. In 1892, she published Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted. One of the first novels by an African-American woman, it sold well and was reviewed widely. Harper continued with her political activism. She helped organize the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 and was later elected vice president in 1897.

Harper died on February 22, 1911.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frances_Harper

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Michael S. Harper

Michael S. Harper

1938-2016

Michael Steven Harper (March 18, 1938-May 7, 2016), an American poet from Brooklyn, was the Poet Laureate of Rhode Island from 1988 to 1993. He published 10 books of poetry, two of which, Dear John, Dear Coltrane (1970) and Images of Kin (1977), were nominated for the National Book Award. A great deal of his poetry was influenced by jazz and history. Many of his poems were included as important examples of African-American literature and jazz poetry in various anthologies. Harper often wrote about his wife, Shirley (commonly referred to as “Shirl”), their children, their ancestors, as well as friends and various black historical and cultural figures.

Harper earned his B.A. and M.A. from California State University, Los Angeles, and an M.F.A. from the University of Iowa. He was the longest-serving professor of English at Brown University, teaching poetry workshops to undergraduates.

He lived in Providence, Rhode Island, until his death on May 7, 2016.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_S._Harper

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

E. Lynn Harris

E. Lynn Harris

1955-2009

Everette “E.” Lynn Harris (June 20, 1955-July 23, 2009) was an American author. He was best known for his depictions of African-American men who were on the down-low and closeted.

Born in Flint, Michigan, Harris grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, and had homes in Houston, Texas, Atlanta, Georgia and Fayetteville, Arkansas. In his writings, Harris maintained a poignant motif, occasionally emotive, that incorporated vernacular and slang from popular culture.

Harris became the first black male cheerleader while attending the University of Arkansas. He was also his college’s chapter president of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. After graduation, he became a computer salesman with IBM for a time. Harris was initially unable to land a book deal with a reputable publishing house for his first work, Invisible Life, so he self-published it through a vanity publisher and sold copies from his car trunk. Since then, 10 of his novels have achieved New York Times bestseller status.

Along with fiction, Harris also penned a personal memoir, What Becomes of the Brokenhearted.

Harris died of heart disease on July 23, 2009, in Los Angeles.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._Lynn_Harris

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Frank Harris

Frank Harris

1856-1931

Frank Harris (February 14, 1856-August 27, 1931) was a British-born, naturalized-American author, editor, journalist and publisher who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day. Though he attracted much attention during his life for his irascible, aggressive personality, editorship of famous periodicals and friendship with the talented and famous, he is remembered mainly for his multiple-volume memoir, My Life and Loves, which was banned in countries around the world for its sexual explicitness.

Harris was born James Thomas Harris in Galway, Ireland, of Welsh parents. At the age of 12, he was sent to Wales to continue his education as a boarder at the Ruabon Grammar School in Denbighshire. Emigrating to the U.S. in late 1869, he studied at the University of Kansas. Returning to England in 1882, Harris first came to general notice as the editor of a series of London newspapers, including The Evening News, The Fortnightly Review and The Saturday Review. Harris returned to New York during World War I. From 1916 to 1922, he edited the U.S. edition of Pearson’s Magazine.

Harris became an American citizen in April 1921. In 1922 he traveled to Berlin to publish his best-known work, his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922-1927).

Harris also wrote short stories and novels, two books about Shakespeare, a series of biographical sketches in five volumes under the title Contemporary Portraits and biographies of his friends, Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw. His attempts at playwriting were less successful: only Mr. and Mrs. Daventry (1900) was produced on the stage.

Harris died in France on August 27 1931, of a heart attack.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Harris

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Joanne Harris

Joanne Harris

1964-

Joanne Michele Sylvie Harris (born July 3, 1964, in Barnsley, Yorkshire) is a British author. Born to a French mother and an English father in her grandparents’ sweet shop, her family life was filled with food and folklore. Her great-grandmother had an odd reputation and enjoyed letting the gullible think she was a witch and healer. All of this was an environment that would play a key role as an adult in the development of Harris’ novels.

She was educated at Wakefield Girls High School, Barnsley, Sixth Form College and St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge, where she read Modern and Medieval Languages.

Her first novel, The Evil Seed, was published in 1989 but it – and a second novel published in 1993 – met with only marginal success. In 1999, her whimsical though slightly dark and mystical story, Chocolat, based on food and an exotic locale in the Gers area of France, reached No. 1 in The Sunday Times newspaper’s bestseller list. The book was short-listed for the 1999 Whitbread Novel of the Year Award; the movie rights were sold to Miramax Pictures. The success of the motion picture, starring Juliette Binoche and Johnny Depp, brought Harris worldwide recognition.

Her novel, Runemarks, published August 2007, is her first book for children and young adults.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joanne_Harris

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Joel Chandler Harris

Joel Chandler Harris

1845-1908

Joel Chandler Harris was an accomplished and well-known writer in his time. He was known for his journalism skills but most of all for his stories narrated by the character, “Uncle Remus.” His early career consisted of work as a typesetter and paragrapher and later as an editor, although he was not well-recognized for his editorial input.

Harris was a shy man and self-conscious of his looks. As an adult, he wore a wide-brimmed hat even indoors to cover his red hair. Because of his shyness, he never appeared publicly to present any of his works. However, he was well known for his sense of humor in his writings and it is believed that perhaps he hid behind his humor because of his low self-esteem. Growing up, he was known to often play practical jokes on his friends, which on several occasions turned out to be harmful to the friend.

Harris was born in Eatonton, Georgia, and was raised by his single mother. His formal education ended by his early teens. At that time, he became a printer’s devil for The Countryman, a local newspaper owned by Joseph Addison Turner. Turner owned the Turnwold Plantation, to which Harris later moved. It was here, at Turnwold, that Harris was first introduced to Negro slaves. He spent many hours with the slaves, listening to their folklore. He had an ear for their dialect and committed to memory both their stories and language. It would later prove to be an asset to his career. In the stories of “Uncle Remus,” Harris was able to capture the reader’s and listener’s attention by his accurate detail of the Negro folklore of the plantation slave. Although other writers had also imitated the language, they were unable to capture it the way Harris did.

Turner’s business collapsed in 1866 with the end of the American Civil War and Harris left Turnwold. He worked as a typesetter for The Macon Telegraph, The New Orleans Crescent Monthly and The Forsyth, Georgia, Monroe Advertiser. After The Advertiser, he became an associate editor of The Savannah Morning News. He married Esther LaRose while living in Savannah in 1873. They had nine children but lost three to childhood illnesses. In 1876, Harris moved his family to Atlanta because of an epidemic of yellow fever in Savannah. It was there that he obtained his job with The Atlanta Constitution.

Harris lived in Atlanta until his death, in 1908, of acute nephritis and cirrhosis of the liver.

Source: http://www.uncp.edu/home/canada/work/allam/18661913/lit/harris.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Bret Harte

Bret Harte

1836-1902

Francis Bret Harte (August 25, 1836-May 6, 1902) was an American author and poet, best remembered for his accounts of pioneering life in California.

He was born in Albany, New York, as Francis Brett Hart. He was named after his great-grandfather, Francis Brett. When he was young, his father changed the spelling of the family name from Hart to Harte. Later, Francis preferred to be known by his middle name but he spelled it with only one “t,” becoming Bret Harte.

He moved to California in 1853, later working there in a number of capacities, including miner, teacher, messenger and journalist. He spent part of his life in the northern California coastal town of Union (now known as Arcata), a settlement on Humboldt Bay that was established as a provisioning center for mining camps in the interior.

The 1860 massacre of between 80 and 200 Wiyots killed at the village of Tutulwat was well-documented historically and was reported in San Francisco and New York by Harte. When serving as assistant editor for The Northern Californian, Harte editorialized about the slayings while his boss was temporarily absent, leaving Harte in charge of the paper. Harte published a detailed account condemning the event. After publishing the editorial, his life was threatened and, one month later, he was forced to flee. Harte quit his job and moved to San Francisco.

His first literary efforts, including poetry and prose, appeared in The Californian, an early literary journal. In 1868, he became editor of The Overland Monthly, another new literary magazine, but this one more in tune with the pioneering spirit of excitement in California. His story, “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” appeared in the magazine’s second edition, propelling Harte to nationwide fame.

When word of Charles Dickens’ death reached Harte in July 1870, he immediately sent a dispatch across the bay to San Francisco to hold back the forthcoming publication of The Overland Monthly for 24 hours so that he could compose the poetic tribute, “Dickens in Camp.”

Determined to pursue his literary career, in 1871 he and his family traveled to New York, and eventually to Boston, where he contracted with the publisher of The Atlantic Monthly for an annual salary of $10,000. His popularity waned, however, and by the end of 1872 he was without a publishing contract and increasingly desperate. He spent the next few years struggling to publish new work or republish old work, delivering lectures about the gold rush and even selling an advertising jingle to a soap company.

In 1878, Harte was appointed to the position of U.S. Consul in Krefeld, Germany, and then to Glasgow in 1880. In 1885, he settled in London. During the 24 years he spent in Europe, he never abandoned writing and maintained a prodigious output of stories that retained the freshness of his earlier work.

He died in England in 1902 of throat cancer and is buried at Frimley.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bret_Harte

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne

1804-1864

Nathaniel Hawthorne (born Nathaniel Hathorne, July 4, 1804-May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. Much of Hawthorne’s writing centers on New England, many works featuring moral allegories with a Puritan inspiration. His fiction works are considered part of the Romantic movement and, more specifically, dark romanticism. His themes often center on the inherent evil and sin of humanity and his works often have moral messages and deep psychological complexity. His published works include novels, short stories and a biography of his friend, Franklin Pierce.

Hawthorne was born in the city of Salem, Massachusetts, to Nathaniel Hathorne and the former Elizabeth Clarke Manning. His ancestors include John Hathorne, a judge during the Salem Witch Trials. Nathaniel later added a “w” to make his name “Hawthorne.” He entered Bowdoin College in 1821, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in 1824 and graduated in 1825.

Hawthorne anonymously published his first work, a novel titled Fanshawe, in 1828. He published several short stories in various periodicals, which he collected in 1837 as Twice-Told Tales. The next year, he became engaged to Sophia Peabody. He worked at a Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a Transcendentalist community, before marrying Peabody in 1842. The couple moved to the Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, later moving to Salem, the Berkshires, then to the Wayside in Concord. The Scarlet Letter was published in 1850, followed by a succession of other novels. A political appointment took Hawthorne and family to Europe before their return to the Wayside in 1860.

Hawthorne died on May 19, 1864, leaving behind his wife and their three children.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nathaniel_Hawthorne

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Robert Hayden

Robert Hayden

1913-1980

Robert Hayden (August 4, 1913-February 25, 1980) was an American poet, essayist and educator. He was appointed Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1976.

Hayden was born Asa Bundy Sheffey in Detroit, Michigan, to Ruth and Asa Sheffey (who separated before his birth). He was taken in by a foster family next door, Sue Ellen Westerfield and William Hayden, and grew up in a Detroit ghetto, nicknamed “Paradise Valley.” The Haydens’ perpetually contentious marriage, coupled with Ruth Sheffey’s competition for young Hayden’s affections, made for a traumatic childhood. Witnessing fights and suffering beatings, Hayden lived in a house fraught with chronic angers whose effects would stay with the poet throughout his adulthood. In addition, his severe visual problems prevented him from participating in activities such as the sports in which nearly everyone was involved. His childhood traumas resulted in debilitating bouts of depression that he later called “my dark nights of the soul.”

Because he was nearsighted and slight of stature, he was often ostracized by his peer group. As a response both to his household and peers, Hayden read voraciously, developing both an ear and an eye for transformative qualities in literature. He attended Detroit City College (Wayne State University) and left in 1936 to work for the Federal Writers’ Project, where he researched black history and folk culture.

He was raised as a Baptist and later became a member of the Baha’i faith during the early 1940s after marrying a Baha’i, Erma Inez Morris. He is one of the best-known Baha’i poets and his religion influenced much of his work.

After leaving the Federal Writers’ Project in 1938, marrying Erma Morris in 1940 and publishing his first volume, Heart-Shape in the Dust (1940), Hayden enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1941 and won a Hopwood Award there.

In pursuit of a master’s degree, Hayden studied under W.H. Auden, who directed Hayden’s attention to issues of poetic form, technique and artistic discipline. Auden’s influence may be seen in the “technical pith of Hayden’s verse.” After finishing his degree in 1942, then teaching for several years at Michigan, Hayden went to Fisk University in 1946, where he remained for 23 years, returning to Michigan in 1969 to complete his teaching career.

He died in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1980, age 66.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hayden

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Mary Hays

Mary Hays

1759-1843

Mary Hays (October 13, 1759-1843) was an English novelist and feminist. She was born in Southwark, London. Almost nothing is known of her first 17 years. In 1779, she fell in love with John Eccles, who lived on Gainsford Street, where she also lived. Their parents opposed the match but the pair met secretly and exchanged more than 100 letters. Tragically, in August 1780, Eccles died of a fever.

For the next 10 years, Hays wrote essays and poems. A short story, “Hermit: An Oriental Tale,” was published in 1786.

In 1791, she wrote a pamphlet with the didactic title, “Cursory Remarks on An Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship,” using the nom-de-plume Eusebia, in response to a chauvinistic essay by Gilbert Wakefield. Hays next wrote the book, Letters and Essays (1793), and invited Mary Wollstonecraft to comment on it before publication. Although the reviews were mixed, Hays decided to leave home and to try to support herself by writing.

Her next work, Memoirs of Emma Courtney (1796), is probably her best-known publication. At about this time, Hays started writing for The Analytical Review, a liberal magazine. Wollstonecraft was the fiction editor and Hays is popularly credited with introducing her to her husband, author William Godwin.

Her next novel, The Victim of Prejudice (1799), is more emphatically feminist and critical of class hierarchies. In 1803, Hays proved her determination and earnestness by publishing Female Biographies, a book in six volumes, containing the lives of 294 women.

The last 20 years of her life were somewhat unrewarding, with little income and only moderate praise for her work. In 1824, Hays returned to London, where she died in 1843.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Hays

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Eliza Haywood

Eliza Haywood

1693-1756

Eliza Haywood (1693-February 25, 1756), born Elizabeth Fowler, was an English writer, actress and publisher. Haywood wrote and published more than 70 works during her lifetime, including fiction, drama, translations, poetry, conduct literature and periodicals.

Haywood gave conflicting accounts of her own life; her origins remain unclear. Some details have been widely accepted, however: She was probably born in Shropshire, England. Her first entry into the public record is in Dublin, Ireland, in 1715 when she was listed as “Mrs. Haywood” in Thomas Shadwell’s Shakespeare adaptation, Timon of Athens; or the Man-Hater, at Smock Alley Theatre. She had an open, live-in relationship with William Hatchett, the father of her second child. She also had a child with Richard Savage.

William Hatchett was a bookseller who shared a stage career with Haywood and the couple were lovers and companions for more than 20 years. They collaborated on an adaptation of Tragedy of Tragedies by Fielding and an opera, The Opera of Operas; or Tom Thumb the Great (1733).

Haywood’s writing career began in 1719 with the first two installments of Love in Excess, a novel, and ended in the year she died with conduct books, The Wife and The Husband, and the biweekly periodical, The Young Lady. She wrote in several genres and many of her works were published anonymously. There is much of Haywood’s writing career that still remains unknown.

She fell ill in October 1755 and died on February 25, 1756.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eliza_Haywood

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt

1778-1830

William Hazlitt, the son of an Irish Unitarian clergyman, was born in Maidstone, Kent, on April 10, 1778. His father was a friend of Joseph Priestley and Richard Price. As a result of his father’s support of the American Revolution, the family was forced to leave Kent and live in Ireland.

The family returned to England in 1787 and settled at Wem in Shropshire. At the age of 15, Hazlitt was sent to be trained for the ministry at New Unitarian College at Hackney in London. The college had been founded by Joseph Priestley and had a reputation for producing free-thinkers. In 1797, Hazlitt lost his desire to become a Unitarian minister and left the college.

In 1805, Joseph Johnson published Hazlitt’s first book, An Essay on the Principles of Human Action. The following year, Hazlitt published Free Thoughts on Public Affairs, an attack on William Pitt and his government’s foreign policy. This was followed by a series of articles and pamphlets about political corruption and the need to reform the voting system.

In 1813, Hazlitt was employed as the parliamentary reporter for The Morning Chronicle, the country’s leading Whig newspaper. However, in his articles, Hazlitt criticized all political parties. Hazlitt also contributed to The Examiner, a radical journal edited by Leigh Hunt. Later, Hazlitt wrote for The Edinburgh Review, The Yellow Dwarf and The London Magazine. In these journals, Hazlitt produced a series of essays about art, drama, literature and politics. During this period, he established himself as England’s leading expert on the writings of William Shakespeare.

Hazlitt wrote several books about literature, including Characters of Shakespeare (1817), A View of the English Stage (1818), English Poets (1818) and English Comic Writers (1819). He continued to write about politics; his most important book was Political Essays with Sketches of Public Characters (1819).

In The Spirit of the Age: Contemporary Portraits (1825), Hazlitt provides a series of contemporary portraits, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Robert Southey, William Cobbett, William Godwin and William Wilberforce. This was followed by The Plain Speaker (1826) and Life of Napoleon (1828-30).

In poverty, William Hazlitt died of stomach cancer on September 18, 1830.

Source: http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/PRhazlitt.htm

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

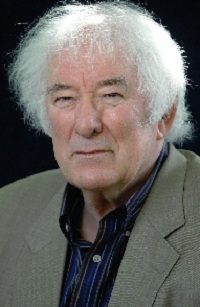

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney

1939-2013

Seamus Heaney (April 13, 1939-August 30, 2013) was a Northern Irish poet, playwright, translator, lecturer and recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Born at Mossbawn farmhouse between Castledawson and Toomebridge, he resided in Dublin.

As well as the Nobel Prize in Literature, Heaney received the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize (1968), the E.M. Forster Award (1975), the Golden Wreath of Poetry (2001), T.S. Eliot Prize (2006) and two Whitbread Prizes (1996 and 1999). He was a member of Aosdana since its foundation and was been Saoi since 1997. He was both the Harvard and the Oxford Professor of Poetry and was made a Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres in 1996.

Heaney died in a Dublin hospital on Friday, August 30, 2013. He had been recuperating from a stroke since 2006.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seamus_Heaney

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lafcadio Hearn

Lafcadio Hearn

1850-1904

Lafcadio Hearn, European-born American author, wrote novels and articles with exotic themes in highly precise and polished prose. He was born June 27, 1850, on the Greek island of Santa Maura. His mother was Maltese and his father a British army surgeon of Anglo-Irish extraction. When Hearn was two years old, his mother abandoned him to an aunt in Dublin, who later sent him to St. Cuthbert’s College to prepare for the priesthood. There he lost his left eye in an accident; he lost much of his religious faith as well. His other eye, strained by incessant reading, bulged badly.

At 19, extremely short, disfigured and psychologically maimed, Hearn arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he eventually became a reporter for The Inquirer. In 1874, he married a local African-American girl, breaking the Ohio laws against miscegenation. The marriage lasted three years and cost Hearn his job. Sent by another periodical to New Orleans, he found there the colorful, exotic ambience that would energize his pen.

By 1881, Hearn had become the successful literary editor of The New Orleans Times Democrat, to which he contributed local-color sketches, obscure folktales and legends and translations of French writers. His first book, One of Cleopatra’s Nights (1882), was a perceptive translation of six Theophile Gautier stories. He also contributed to Harper’s Weekly and The Century. His literary propensities were becoming more obvious; he was attracted by the romantic, strange and grotesque, but he presented these against real backgrounds or with real people. He published a book of obscure legends and stories, Stray Leaves from Strange Literature (1884) and Some Chinese Ghosts (1887). He lived for two years in the West Indies, where he wrote his first novels, Chita (1889), a Rousseauesque romance, and Youma (1890), concerning a slave rebellion. Both narratives illustrate his deft, polished, precise prose and emphasis on description, which often overshadow the brittle and abstract plot and characterization.

In 1890, Hearn was commissioned to go to Japan but, shortly after arriving, he quarreled with his publisher and found himself unemployed. For a while, he taught English at a government school in Matsue and freelanced newspaper articles. His life in Japan was greatly enhanced by his marriage to Setsuko Koizumi, whose family adopted him. As Yakumo Koizumi, Hearn found his final nationality and an estimable academic position as professor of literature at the Imperial University of Tokyo. During this happy period, Hearn composed his best prose – minute examinations of Japan, its people and its folkways – in books such as: Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894); Kokoro (1896); Gleanings in Buddha-Fields (1897); Exotics and Retrospectives (1898); In Ghostly Japan (1899); Shadowings (1900); and Kwaidan and Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation (1904).

He died in Okubo, Japan, on September 26, 1904.

Source: http://www.answers.com/topic/lafcadio-hearn

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Amy Heckerling

Amy Heckerling

1954-

Amy Heckerling (born May 7, 1954) is an American film director, one of the few female directors to have produced multiple box-office hits.

Heckerling was born in the Bronx to a bookkeeper mother and a certified public accountant father. She attended the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan, graduating in 1970, and studied film at New York University. She received her master’s degree from the AFI Conservatory.

Heckerling’s first feature was Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982). Her next film, Johnny Dangerously (1984), was an Airplane!-style spoof of gangster movies. The following year, she directed National Lampoon’s European Vacation (1985).

In 1989, Heckerling had her biggest success to date with Look Who’s Talking. Two sequels followed, the first of which (1990’s Look Who’s Talking ,Too) Heckerling also directed and co-wrote. In 1995, she wrote and directed Clueless.

Heckerling directed and produced Loser (2000). Her romantic comedy, I Could Never Be Your Woman, was released in 2007.

In 2011, she directed the horror-comedy film, Vamps.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amy_Heckerling

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Frederick Henry Hedge

Frederick Henry Hedge

1805-1890

Frederic Henry Hedge (1805-August 21, 1890) was a New England Unitarian minister and Transcendentalist. He was a founder of the Transcendental Club, originally called Hedge’s Club, and active in the development of Transcendentalism.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Hedge was the son of Harvard University professor Levi Hedge. At the age of 12, he traveled to Germany and studied music for five years. He then entered Harvard as a junior and graduated in 1825. His knowledge of German was to serve him well, both in hymnody – he translated Luther’s “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”) into the most popular English version – and in philosophy, where it allowed him a greater familiarity with Kant than most of the Americans of his day.

After graduating as valedictorian, he enrolled in Harvard Divinity School, where he met his intimate friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson. After graduating from the Divinity School, Hedge was ordained as a Unitarian minister in 1829 and became minister at a Unitarian church in West Cambridge. In 1835, he took charge of a church in Bangor, Maine; in 1850, after spending a year in Europe, he became pastor of the Westminster Church in Providence, Rhode Island and, in 1856, of the church in Brookline, Massachusetts.

He was central to the development of Transcendentalism in the 1830s. On September 8, 1836, Hedge met with Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Putnam and George Ripley in Cambridge to discuss the formation of a new club. Eleven days later, on September 18, Ripley hosted their first official meeting at his house; the group would eventually be known as the Transcendental Club. Its first official meeting was attended by Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson, James Freeman Clarke and Convers Francis, as well as Hedge, Emerson and Ripley. Future members would include Henry David Thoreau, William Henry Channing, Christopher Pearse Cranch, Sylvester Judd and Jones Very. The group planned its meetings for times when Hedge was visiting from Bangor, Maine, leading to the early nickname, “Hedge’s Club.”

Hedge wrote: “There was no club in the strict sense … only occasional meetings of like-minded men and women,” earning the nickname “the brotherhood of the Like-Minded.” He became alienated from the group’s more extreme positions in the 1840s and did not publish in the Transcendental journal, The Dial, despite his friendship with its editor, Margaret Fuller, saying he did not want to be associated with the movement in print.

He was noted as a public lecturer as well as a pulpit orator. In 1853-1854, he lectured on medieval history before the Lowell Institute.

In 1858, Hedge returned to Harvard Divinity School as a professor of ecclesiastical history; that year, he also became editor of The Christian Examiner, a role he held for three years. The next year, Hedge began a four-year term as president of the American Unitarian Association. From 1872 until 1882, he taught German literature at Harvard.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Henry_Hedge

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Robert Heinlein

Robert Heinlein

1907-1988

Robert Anson Heinlein (July 7, 1907-May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction writer. Often called the “dean of science fiction writers,” he was one of the most influential and controversial authors of the genre. He set a standard for science and engineering plausibility and helped to raise the genre’s standards of literary quality. He was one of the first science fiction writers to break into mainstream magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post in the late 1940s. He was one of the best-selling science fiction novelists for many decades. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were known as the “Big Three” of science fiction.

Heinlein was one of a group of writers who came to prominence under the editorship of John W. Campbell Jr. in his Astounding Science Fiction magazine – though Heinlein denied that Campbell influenced his writing to any great degree.

Within the framework of his science fiction stories, Heinlein repeatedly addressed certain social themes: The importance of individual liberty and self-reliance, the obligation individuals owe to their societies, the influence of organized religion on culture and government and the tendency of society to repress nonconformist thought. He also examined the relationship between physical and emotional love, explored various unorthodox family structures and speculated on the influence of space travel on human cultural practices. His approach to these themes led to wildly divergent opinions on what views were being expounded via his fiction.

The 1961 novel, Stranger in a Strange Land, is viewed by many as his masterpiece, incorporating many of the aforementioned themes found in his literature. It also contains perhaps the clearest explication of Heinlein’s metaphysical, and possibly spiritual, philosophy, encapsulated in the iconic phrase, “Thou art god.” This philosophy resonated greatly with readers in the counterculture at the time. Since its publication, Stranger in a Strange Land has been a classic among counterculture readers. It has enjoyed widespread success and is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest science fiction novels ever written.

Heinlein won Hugo Awards for four of his novels; in addition, 50 years after publication, three of his works were awarded “Retro Hugos” – awards given retrospectively for years in which Hugo Awards had not been awarded. He also won the first Grand Master Award, given by the Science Fiction Writers of America, for his lifetime achievement.

In his fiction, Heinlein coined words that have become part of the English language, including “grok” and “waldo,” and popularized the term, “TANSTAAFL.”

Heinlein died in his sleep from emphysema and heart failure on May 8, 1988.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_A._Heinlein

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lyn Hejinian

Lyn Hejinian

1941-

Lyn Hejinian (born May 17, 1941) is an American poet, essayist, translator and publisher. She is often associated with the Language poets and is well known for her landmark work, My Life (1980), as well as her book of essays, The Language of Inquiry (2000).

Hejinian was born in the San Francisco bay area and now lives in Berkeley, California, with her husband, composer/musician Larry Ochs. She has published more than a dozen books of poetry and numerous books of essays, as well as two volumes of translations from the Russian poet, Arkadii Dragomoshchenko. Between 1976 and 1984, she was editor of Tuumba Press and, from 1981 to 1999, she co-edited (with Barrett Watten) Poetics Journal. She is currently co-editor of Atelos, which publishes cross-genre collaborations between poets and other artists.

Hejinian has herself worked on a number of collaborative projects with painters, musicians and filmmakers. She teaches poetics at University of California, Berkeley, and has lectured in Russia and around Europe. She has received grants and awards from the California Arts Council, the Academy of American Poets, the Poetry Fund, the National Endowment of the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyn_Hejinian

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Joseph Heller

Joseph Heller

1923-1999

Joseph Heller (May 1, 1923-December 12, 1999) was a U.S. satirical novelist, short story writer and playwright. His best known work is Catch-22, a novel about U.S. servicemen during World War II. The title of this work entered the English lexicon to refer to absurd, no-win choices, particularly in situations in which the desired outcome of the choice is an impossibility and, regardless of choice, the same negative outcome is a certainty.

Heller is widely regarded as one of the best post-World War II satirists. Although he is remembered primarily for Catch-22, his other works center on the lives of various members of the middle class and remain exemplars of modern satire.

He died of a heart attack at his home in East Hampton, on Long Island, in December 1999, shortly after the completion of his final novel, Portrait of an Artist as an Old Man.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Heller

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Lillian Hellman

Lillian Hellman

1905-1984

During the 1930s, it was fashionable to be a part of the radical political movement in Hollywood. Lillian Hellman devoted herself to the cause along with other writers and actors in their zeal to reform. Her independence set her apart from all but a few women of the day and gave her writing an edge that broke the rules.

Born in New Orleans in 1905, but raised in New York after the age of five, she studied at Columbia. She married Arthur Kober in 1925, did some work in publishing and wrote for The Herald Tribune. When her husband, also a writer, got a job with Paramount, they moved to California.

Her first important work was the play, The Children’s Hour, which was based on a true incident in Scotland. This was an amazingly successful play and gave Hellman a definite standing in the literary community. Her next venture, however, a play called Days to Come, was a complete failure. After its publications she went to Europe. There, she witnessed the Spanish Civil War and traveled around with Ernest Hemingway. When back in the States, she wrote The Little Foxes, which opened in 1939 and was a financial windfall for her. She also followed Dorothy Parker and other highly esteemed writers to Hollywood, where she was well compensated for her screenwriting efforts.

While it may have been fun and daring to be part of a radical political group in the 1930s, with the ’40s came the Un-American Activities Committee. She was forced to testify in government hearings and faced the threat of black lists and tax problems.

She remained a visible force and became almost an icon in her later years. Despite an assortment of health issues, including being practically blind, she traveled, lectured and promoted her political beliefs.

She was 79 when she died in 1984.

Source: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0375484/bio

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

Felicia Hemans

Felicia Hemans

1793-1835

Felicia Hemans (September 25, 1793-May 16, 1835) was an English poet. She was born in Liverpool, a granddaughter of the Venetian consul in that city. Her father’s business soon brought the family to Denbighshire in North Wales, where she spent her youth. They made their home near Abergele and St. Asaph (Flintshire).

Her first poems, dedicated to the Prince of Wales, were published in Liverpool in 1808, when she was only 14, arousing the interest Percy Bysshe Shelley, who briefly corresponded with her. She quickly followed these with “England and Spain” (1808) and “The Domestic Affections,” published in 1812, the year of her marriage to Captain Alfred Hemans, an Irish army officer some years older than herself. The marriage took her away from Wales, to Daventry in Northamptonshire, until 1814.

Marriage had not prevented her from continuing her literary career, with several volumes of poetry being published by the respected firm of John Murray in the period after 1816, beginning with The Restoration of the Works of Art to Italy (1816) and Modern Greece (1817). Tales and Historic Scenes was the collection published 1819, the year of her separation from her husband.

From 1831 onward, she lived in Dublin, where her younger brother had settled, and her poetic output continued. Her major collections, including The Forest Sanctuary (1825), Records of Woman and Songs of the Affections (1830), were immensely popular, especially with female readers. Her last books, sacred and profane, are the substantive Scenes and Hymns of Life and National Lyrics and Songs for Music.

She was a well-known literary figure, highly regarded by contemporaries such as Wordsworth and had a popular following in the United States and the United Kingdom. When she died of dropsy, Wordsworth and Walter Savage Landor composed memorial verses in her honor.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Felicia_Hemans

Bibliography

Bibliography

Press your browser’s BACK button to return to the previous page.

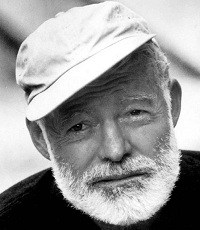

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway

1899-1961